In 2016, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) famously advised all sexually active women of reproductive age to refrain from drinking, lest they inadvertently harm a theoretical fetus. That guidance was based in part on the CDC’s estimate that 3.3 million American women were “at risk of exposing their developing baby to alcohol” every month, should they turn out to be pregnant.

Now a new study (pdf) published on Jan. 11 in the journal Women’s Health Issues is challenging the CDC’s claim—a finding that sheds light on the judgment and criticism faced by women of childbearing age.

A team led by Sarah Roberts and Kirsten Thompson, at the Department of Gynecology at the University of California- San Francisco, used the same data set as the CDC to assess women’s potential risk for alcohol exposure during pregnancy. The dataset included fertile women between 15 and 44, extrapolated from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth.

In getting to its 3.3 million estimate, the CDC started with the assumption that any woman who had had unprotected sex and consumed at least one drink in the previous month could have a pregnancy at risk of alcohol exposure. ”That’s not the right way to do this,” says Roberts. The main problem? The CDC’s calculations reflect the maximum number of pregnancies that could potentially be exposed to alcohol—as opposed to the most likely estimate.

To get a better estimate, the researchers changed two elements of the calculations. First, they raised the number of drinks a woman had to have consumed in the past 30 days to be considered “at-risk” from one to seven. Roberts explained that in relation to preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancies, the CDC itself focuses on this level of drinking as potentially harmful.

Second, the study took all outcomes of pregnancies into account: births, miscarriages, and abortions.

To estimate the number of women who had more than one drink on seven days in the previous 30 days, the authors surveyed 5,016 fertile women between 15 and 44. For pregnancy outcomes, they used national survey data, which say only about 38% cases of unprotected sex result in pregnancy, and 64% of pregnancies end up in births.

Their findings were drastically different: While the CDC found that 3.3 million women every month were at risk of exposing the fetus to alcohol, the study found that the number was about 750,000—less than a quarter of the CDC’s original estimate.

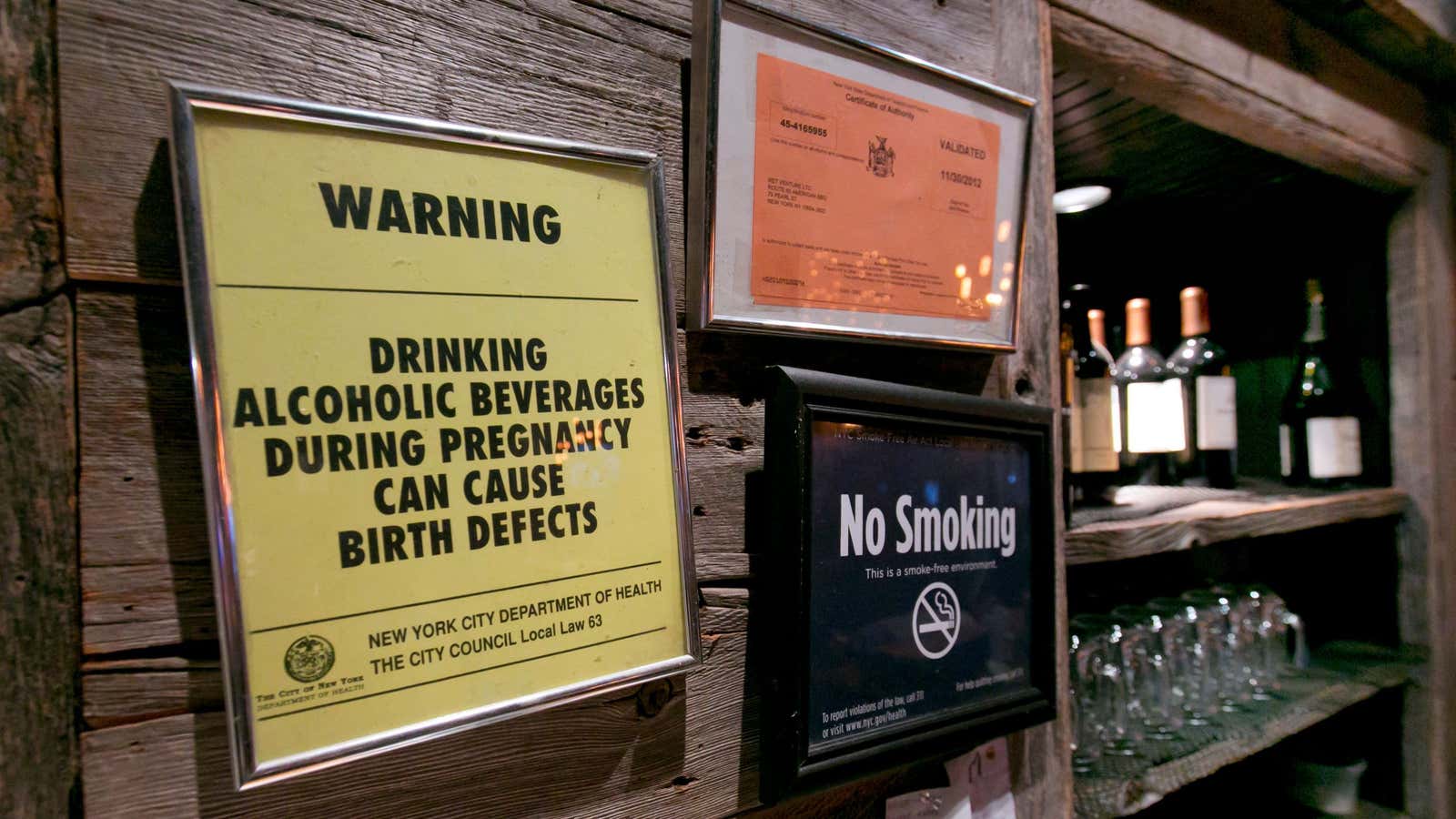

Roberts says the CDC’s overestimate could have generated negative effects, having “contributed to a sense of moral panic around the topic.” After all, in much of the US, drinking alcohol during pregnancy isn’t just discouraged—it’s a punishable offense. Twenty-three states, as well as Washington, DC, say that pregnant women who use alcohol or other drugs are committing a form of child abuse. Lawmakers, particularly in conservative states, routinely attempt to pass laws that would make drinking or using drugs during pregnancy a crime punishable with jail time.

Such efforts speak to an overarching attitude that looks at women primarily as vessels for children, focusing nearly exclusively on the fetus’s well-being, while paying little attention to the mother’s. This is an approach that has dangerous consequences for women’s health.

The CDC routinely revises estimates such as the one that was published in 2016. Hopefully, in the next, it will be able to revise it to get better accuracy. “It would be great if future efforts could take into account this method,” Roberts says.