Rocket start-up Relativity leased a launch pad from the US Air Force

Relativity, a rocket-building start-up founded by alumni of Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, has taken over a US government launch pad.

Relativity, a rocket-building start-up founded by alumni of Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, has taken over a US government launch pad.

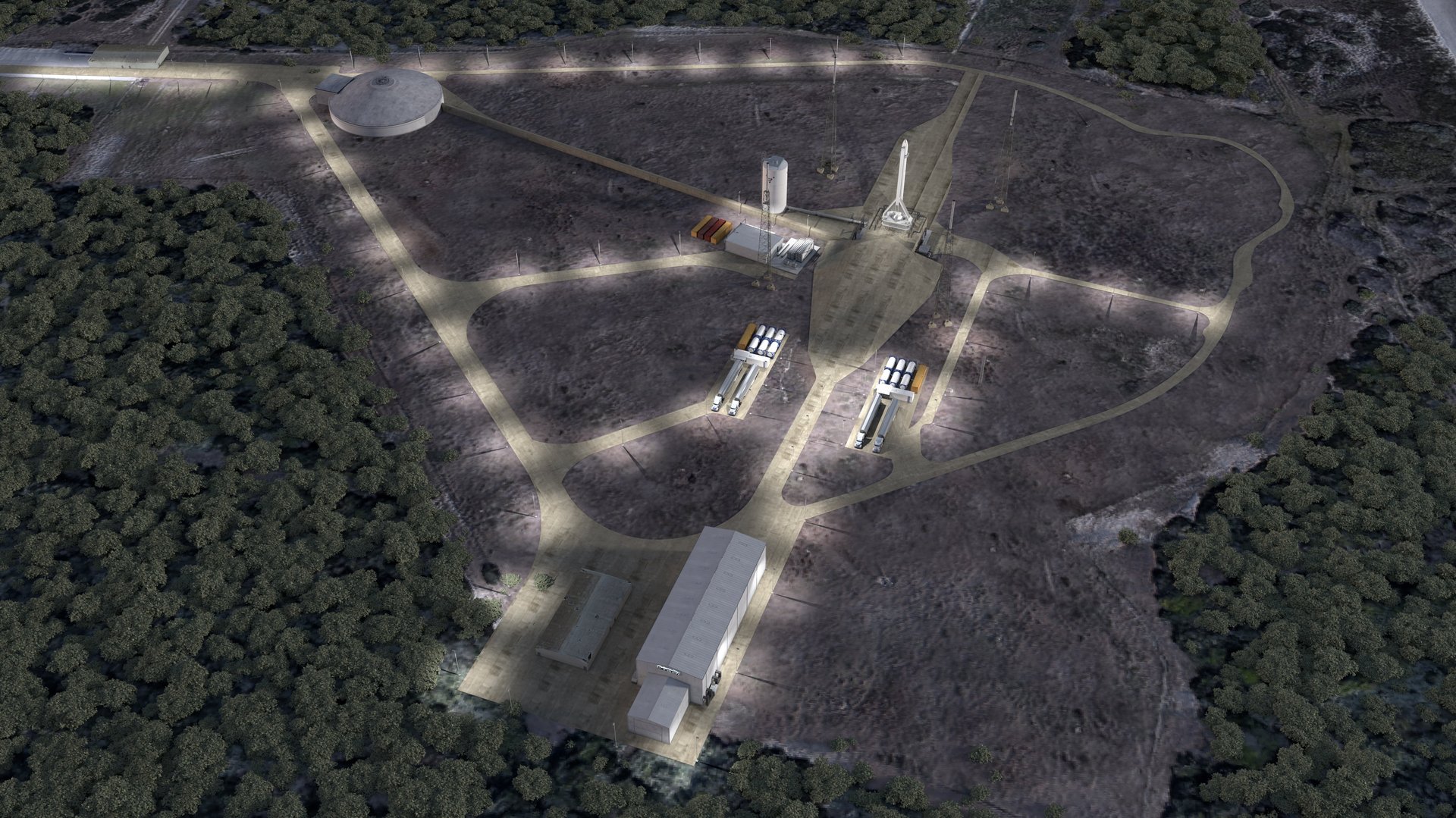

Relativity announced a contract with the US Air Force to operate Space Launch Complex 16 at Cape Canaveral Air Station in Florida, which once launched the first US ballistic missiles as part of a neighborhood of launch sites known as “missile row” and hasn’t been used since 1988.

Launch sites are vital for rocket companies. Departing Earth from the right place makes the trip more efficient, complying with a raft of safety regulations is easier inside a government facility, and launching most rockets requires extensive infrastructure to fuel and control them, as well as to carefully load satellites before launch.

Relativity is just the fourth company to lease a launch pad from the US Air Force at Cape Canaveral. If it passes through environmental and other reviews and launches its rockets, it will have a 20 year exclusive lease on the pad. The company has a similar deal to test its engines at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi.

The Los Angeles-based start-up, whose backers include Y Combinator, Social Capital, and Playground Capital, has designed an advanced robotic manufacturing system it calls Stargate to 3D print as much of the rocket as possible.

These methods, says CEO Tim Ellis, will reduce the number of parts from 100,000 to 1,000, which the company hopes will deliver a cheaper and more reliable vehicle to launch the small satellites driving venture investment in space. The company hopes its first rocket, Terran-1, will fly before the end of 2020. The rocket is expected to carry about a ton of payload into orbit.

Following the end of NASA’s space shuttle program in 2011, officials at Cape Canaveral and nearby Kennedy Space Center made plans to transition the Florida complex into a “multi-user spaceport.” That meant leasing out facilities to private companies, in order to create jobs, save on maintenance costs, and bolster US space technology.

United Launch Alliance, the joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed Martin that briefly held a monopoly on US satellite launches, has leased as many as eight pads from the government to manage a fleet made up of spacecraft that use two different rocket designs. Now, as it replaces those rockets with a new design called Vulcan, it plans to scale back to two pads.

The pressure on ULA to build a new rocket comes in part from its upstart rival SpaceX, which first won the right to operate from a US Air Force launch site in 2004. Now, it operates three launch sites at Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Former SpaceX engineer Tim Buzza, currently an adviser at Relativity, helped develop both companies’ approach to launch facilities.

SpaceX’s biggest pad victory was winning the lease to the Kennedy Center’s Space Launch Complex 39-A, once home to the Space Shuttle and Apollo program, in 2013. It competed (acrimoniously) against Blue Origin to win that bid. Today, Bezos’ company has its own digs nearby, leasing Space Launch Complex 36 within sight of the $250 million factory the Amazon founder has built to produce its rocket, the New Glenn.

A new generation of small rocket makers are facing similar decisions about where to fly their rockets. The leader is Rocket Lab, which launched 24 satellites on three rockets in 2018. It built its own spaceport in New Zealand, a huge challenge according to CEO Peter Beck, but worth it because of the “unprecedented” flight frequency he hopes to achieve at his own facility; the company also has a deal to launch rockets from NASA’s Wallops Space Center in Virginia.

Other contenders are pad-agnostic. Virgin Orbit will launch its rockets from a plane, and only needs to worry about integrating its satellites at a convenient air field. Vector, led by members of SpaceX’s founding team, has designed its rocket around a mobile transporter-erector-launcher that will allow it to launch from just about anywhere, given regulatory approval.

Relativity is focused on beginning design and construction at the new pad, and hiring more members of its team, which recently grew to 60 people.

“Keep hiring more amazing people, printing rockets, stay on track for the first orbital launch—that’s my New Year’s resolution,” Ellis says.