The Trump border wall faces a serious legal obstacle

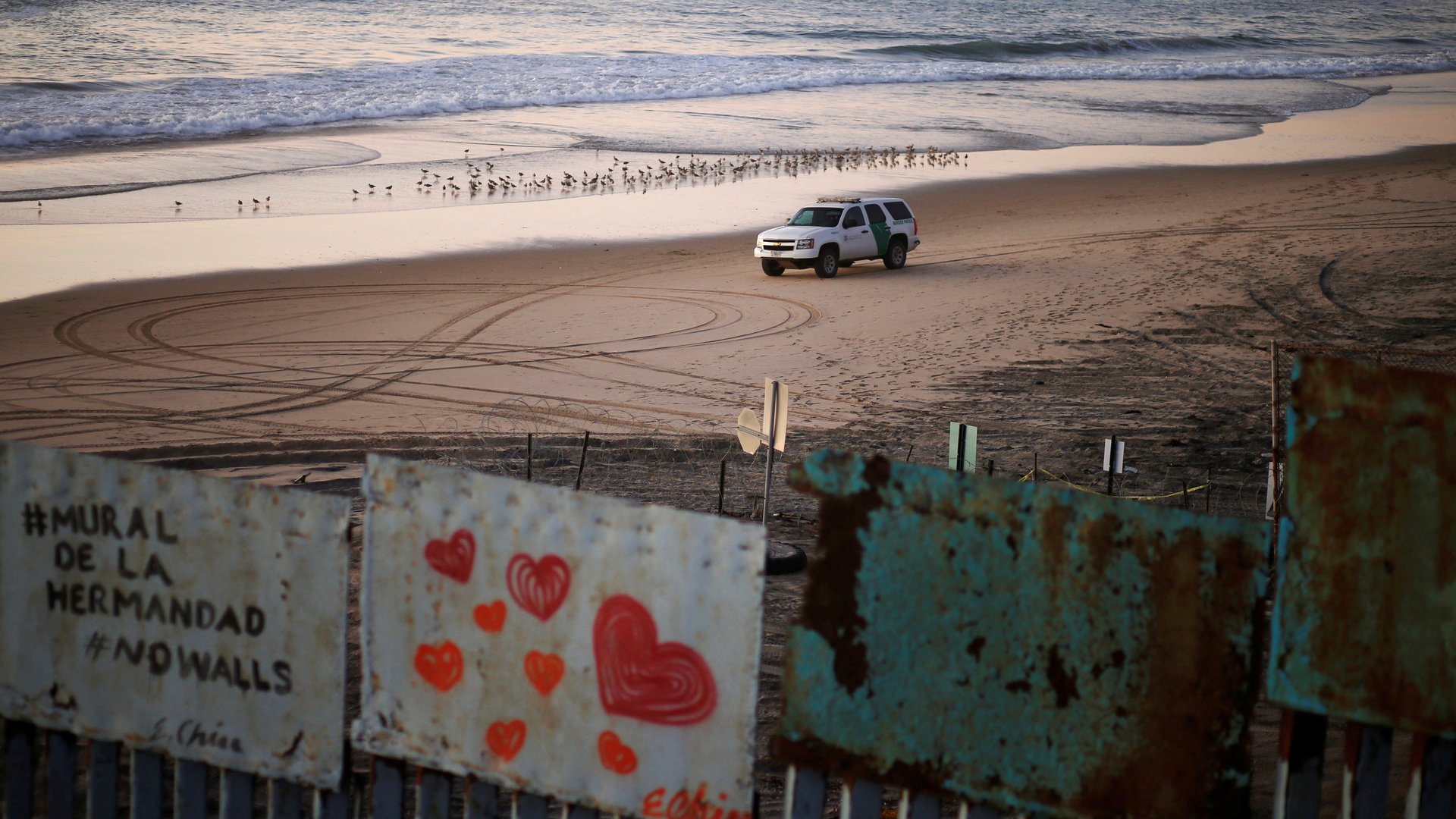

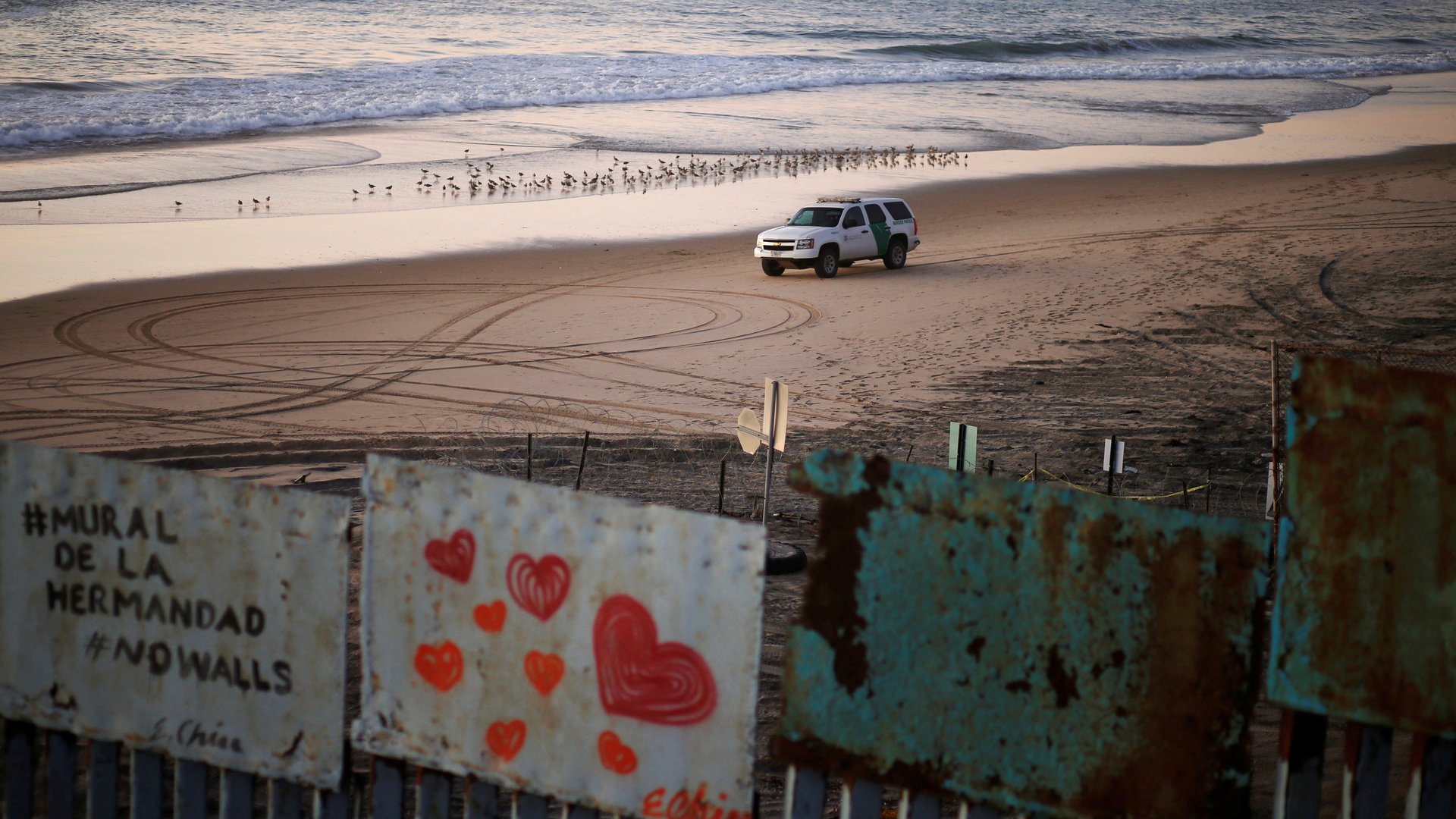

US president Donald Trump has staked a lot on his plans to build a wall along the border with Mexico. He has shut down the federal government over its alleged failure to budget sufficiently for this project and insists that a barrier will solve drug trafficking and immigration woes, even threatening to declare a national emergency to get this done.

US president Donald Trump has staked a lot on his plans to build a wall along the border with Mexico. He has shut down the federal government over its alleged failure to budget sufficiently for this project and insists that a barrier will solve drug trafficking and immigration woes, even threatening to declare a national emergency to get this done.

His insistence is disconcerting, sure. However, his plan is not realistic. Apart from structural issues and political opposition, the wall plan faces a serious legal barrier—the “Takings Clause” of the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution.

The Takings Clause addresses eminent domain law, or the right of the federal government to take private property for a public purpose. It states that “private property [shall not] be taken for public use, without just compensation.” In other words, the US has to pay a property owner for any land it takes and that payment must be fair.

On the surface that doesn’t sound like a huge problem for the government. Theoretically, Trump could just take border property and pay any private landowners. But the US-Mexico border runs along nearly 2,000 miles in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas, which means a lot of takings, extensive legal disputes, and protracted wrangling over what constitutes “just compensation” and whether the public purpose Trump proposes qualifies.

Also notable, it means messing with Texans. The land along the Rio Grande—Texas’s riverine border with Mexico—is 95% privately owned. Congress in March funded 33 miles of walls and fencing in South Texas. The government’s plan is to construct the barriers across private land in the Rio Grande Valley through property belonging to private citizens, ranchers, environmental groups, and the 19th-century La Lomita Catholic chapel.

Local landowners aren’t just sitting back waiting for it to happen. They’re lawyering up and fighting back. The “cowboy priest” Roy Snipes at La Lomita chapel, who is a fan of rescue dogs and Lone Star beer, is no champion of Trump’s wall. He told the Texas Observer, “It’ll be ugly as hell. And besides that, it’s a sick symbol, a countervalue. We don’t believe in hiding behind Neanderthal walls.”

Snipes has the support of the bishop of the Diocese of Brownsville, reverend Daniel Flores. They have refused to allow federal officials to survey the church property, forcing the government to file a lawsuit. In October, the diocese said in a statement (pdf) that “the filing in court was not unexpected.” The church explained its position, arguing:

While the bishop has the greatest respect for the responsibilities of the men and women involved in border security, in his judgment church property should not be used for the purposes of building a border wall. Such a structure would limit the freedom of the Church to exercise her mission in the Rio Grande Valley, and would in fact be a sign contrary to the Church’s mission. Thus, in principle, the bishop does not consent to use church property to construct a border wall.

Apart from arguments based on eminent domain law—the diocese states that there is no compelling governmental interest in building a barrier there—the church argues that a federal taking would violate its First Amendment guarantee of religious freedom. “The wall would have a chilling effect on people going there and using the chapel, so in fact, it’s infringing or denying them their right to freedom of religion,” according to David Garza, the attorney representing the diocese.

Individual citizens are also resistant. On Jan. 10, landowner Eloisa Cavazo told Talking Points Memo that no amount of money could induce her to allow the government to buy her 64-acre property along the Rio Grande for the wall project. “You could give me a trillion dollars and I wouldn’t take it,” she said.

While the government has won takings cases before, many lawyers argue that the proposed border wall will not get built. Elie Mystal, executive editor of Above the Law, who describes himself as “basically a Republican when it comes to takings,” writes in a recent editorial, “There’s no conceivable way that the courts are going to let the government take all of this land, for a dubious public use, when less intrusive measures can be used to accomplish the stated public purposes, at a price point that the government is willing or able to pay.”

Trump has already said that he would invoke the “military version of eminent domain” to take property without due process or just compensation. Basically, he’d declare a national emergency, call the border a national security matter, and grab up land. Military department secretaries can “acquire any interest in land” if “the acquisition is needed in the interest of national defense.”

But this a typical Trump oversimplification. There isn’t exactly a military eminent domain law and there is no doubt that private landowners, nonprofits, and affected government branches will challenge this formulation, which is probably why for all of his huffing and puffing Trump still hasn’t declared that national emergency he keeps threatening.

In Congress, on the House Armed Services Committee, there is already bipartisan support for a legal challenge should the president make good on his threats. Meanwhile, Justin Amash, a Republican representative from Michigan, this month introduced legislation that would prevent “quick takes” like those Trump proposes. Amash’s Eminent Domain Just Compensation Act would bar governmental seizures before just compensation has been established, meaning the federal government—even if resorting to national emergency exigencies—would have to reach agreements with landowners or fight it out in court. And that’s a bill proposed by a Republican who doesn’t even necessarily oppose building a border wall.

Basically, the wall will not be built without years of litigation and then only if the feds can convince the courts that the government takings are justified. As Mystal at Above the Law points out, if the takings cases that would no doubt arise from the federal government’s efforts reach the Supreme Court down the line, conservative and liberal justices alike will be united in their opposition to Trump’s expansive interpretation of eminent domain law.

The constitution’s Fifth Amendment lays out takings law, and no statute on national emergencies can render the nation’s founding legal document irrelevant. Also, liberal justices will not consider the border situation a national security measure warranting extreme relief for the government, and conservative justices are not generally keen on takings. None will want to create a dangerous precedent that allows the US president to just ignore the constitution and grab private property up willy-nilly with no just compensation or due process.

That would be downright un-American.