“We need a new architecture for this new world,” Hillary Clinton said in her farewell speech as US secretary of state. “[One] more Frank Gehry than formal Greek.”

Foreign-policy experts often refer to the global order that emerged after World War II as an “architecture.” To Clinton, the world’s outmoded political architecture resembled the Parthenon in Greece, with clear lines, clear rules, and big institutions as pillars. It once was remarkably sturdy but had now served its cause. “Where once a few strong columns could hold up the weight of the world, today we need a dynamic mix of materials and structures.”

Architecture is politics, and politics is architecture. Both are tested and sometimes torn apart by the shifting and accelerating pace of life, pressing against our physical and imagined walls. Sometimes these structures are metaphoric—the fortresses we construct from tariffs, immigration policies, and culture—and other times, they are literal. “I will build a great wall,” said then-US-presidential candidate Donald Trump in 2015. “Nobody builds walls better than me.”

Architecture has always been political, casting constellations of ideas, interests, and power in stone. From Thomas Jefferson, a founding father of the US, to Albert Speer, Adolf Hitler’s wartime production and construction minister, architect-politicians have left a lasting imprint on modern history. As former UK prime minister Winston Churchill said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

The current global architecture was shaped by the Great Depression and two devastating World Wars—and it certainly did shape us in return. It gave birth to a world that has little in common with the one by which it was created: China, which in the 1940s was an isolated, agrarian country torn apart by civil war, is now a leading global power in everything from artificial intelligence to wireless technologies; the European Union, which was meant to create an “ever closer union” in Europe is fracturing from within; and the US, which for most of the post-war era was the dominant driver of globalization, is now neglecting or even leaving some of the multilateral institutions it championed.

In this new world, global cooperation is on the defense, and the architecture we built to sustain globalization is eroding. But a new era of globalization is nevertheless knocking on the world’s door, with digital trade, online IP rights, cyberattacks, and the problems posed by climate change becoming ever more relevant.

At the 2019 Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos this week, we will be drafting a blueprint to construct a geopolitical framework that can support this era’s needs. This year’s theme—“Globalization 4.0: Shaping a Global Architecture in the Age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution”—will provide the pillars on which we can build.

New powers, problems, and technological possibilities are pushing hard against structures that were built for other purposes and other times. We need a new architecture—but where to start?

To serve—and protect

As technological progress accelerates the movement of everything, once powerful structures turn into straitjackets. One of the oldest forms of architecture—and still one of its extremes—is the fortress. It best illustrates the trade-off between openness and closedness, which China’s president Xi Jinping emphasized in a 2017 speech at the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland:

Pursuing protectionism “is like locking oneself in a dark room. While wind and rain may be kept outside, that dark room will also block light and air.”

Every architect must locate the form she creates somewhere between complete blockage and complete passage, between fortress and open square. The chosen point on the sliding scale between closedness and openness—between blocking wind and rain and letting in sunshine and air—remains architecture’s most significant trade-off.

It’s one of contemporary politics’ most pressing considerations, too. In the 1970s, China’s political leaders knocked down the protective economic fortress the country had built, increasingly opening themselves to imports and (limited) foreign investment. But in the 2000s, they also built a new digital firewall, both locking their “netizens” in, and keeping foreigners out of many matters of digital China.

A similar architectural reconfiguration happened in the US, which until the 2000s was one of the world’s most vigorous advocates of free trade and global governance. Recently it has pulled the brake on that stance, fearing that the country’s openness had led its own citizens to feel exposed to foreign cultures and workers. Unable to build a fortress around the whole economy, it now seeks to build an actual border wall aimed at curbing the inflow of drugs and people along its southern border.

The act of building and breaking fortresses and walls is utmost political. It is the foremost instrument in the toolkit of policy-makers, for it shapes the flow of people, products, and information. And yet, often those who are building the walls are not those who are tearing them down—but rather those who were meant to be kept out.

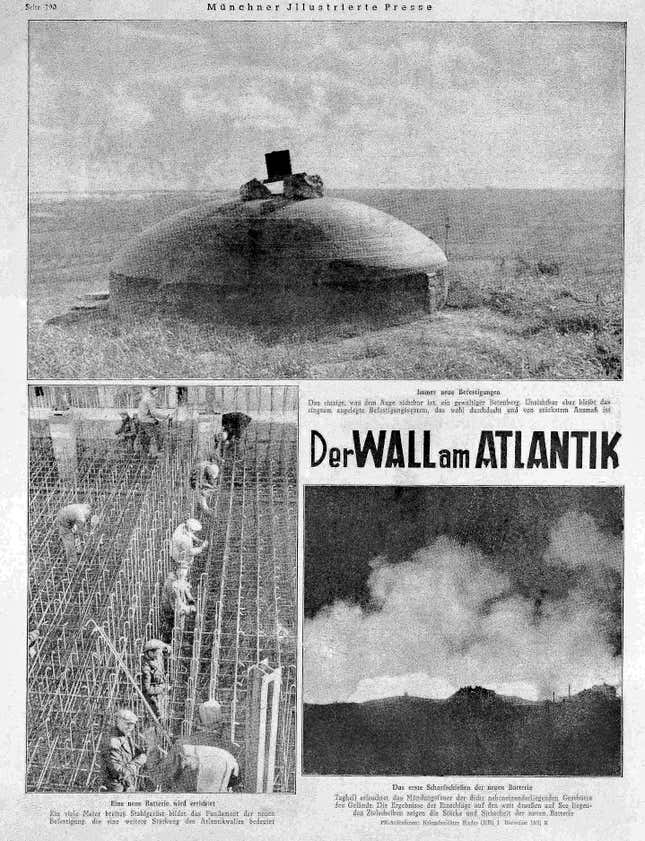

Maybe the most radical example of this is the fall of the modern world’s most bombastic and most grotesque amalgamation of architecture and politics: Nazi Germany’s “Atlantic Wall.” This extensive system of coastal defensive fortifications between 1942 and 1944 had over 15,000 concrete structures. The beaches of the Normandy are still laced with bunkers that sheltered the Wehrmacht soldiers and surrounded the Nazi regime.

“Fortress Europe,” as it was also known, was conceived by Albert Speer, who had embarked on a steep career path from Hitler’s chief architect to one of the masterminds of the regime’s strategy of “total war.” As the war intensified, Speer’s bunkers reached monstrous proportions; they became almost organic signs of the rising pressure on the regime, symbolizing not so much power as an obsession with disappearance and obsolescence.

The day the allied troops landed in Normandy in June 1944, the Atlantic Wall fell. Four years of construction and calculation was undone in one day as the wall was unable to withstand the amphibious attack of the Allies on D-Day, in which thousands of men lost their lives. The fortresses of the Atlantic Wall were built to protect, but eventually gave in to the massive mobilization and acceleration of people and projectiles. Their ruins remind us less of the consequence of power than its transience.

To Paul Virilio, the French cultural theorist and acclaimed chronicler of the Atlantic Wall, the fall not only marked the end of the Nazi regime: It also reflected a deeper shift in the relationship between politics and architecture.

“These concrete blocks were in fact the final throw-offs of the history of frontiers, from the Roman limes to the Great Wall of China; the bunkers, as ultimate military surface architecture, had shipwrecked at lands’ limits, at the precise moment of the sky’s arrival in war; they marked off the horizontal littoral, the continental limit. History had changed course one final time before jumping into the immensity of aerial space.”

Virilio describes how the once-revered architecture of the Atlantic Wall was outmoded by societal advances. Technology is acceleration. Speed triumphs over structure. If architecture is vulnerable to bombs, it is even more exposed to information passing through doors and walls.

Our world today finds itself again at an inflection point where new technologies, combined with new constellations of power and interests, are pressing hard against political and physical architectures. It’s time to draw up a new blueprint.

The new global architecture

The post-Cold War age of hyper-globalization is often associated with the dismantling of walls. But, on closer inspection, it was a reconfiguration. While the walls around states became perforated, the market itself became more encased and protected by international regimes and institutions. The election of Donald Trump, the Brexit vote, and the rise of parties at the extreme ends of the political spectrum around the globe reflect a growing dissatisfaction with this architectural turn.

Such has also been the case for the European Union, the world’s most radical example of a super-structure replacing national sovereignty. It was designed to create more freedom of movement for people, goods, and services, but it ended up feeling stifling to many of the very citizens who lived in it. Whether in Britain, Italy, or even Germany, populations lost their sense of agency over the shaping of rules and laws.

As the EU represents, our global architecture is at a breaking point. Five years after Clinton’s speech, US secretary of state Mike Pompeo called again for a new architecture at a conference of the German Marshall Fund. “Every nation—every nation—must honestly acknowledge its responsibilities to its citizens and ask if the current international order serves the good of its people as well as it could,” he said. “And if not, we must ask how we can right it.”

Instead of the more fluid approach suggested by Clinton, Pompeo asserted the primacy of the nation-state’s sovereignty and its right to build walls and fortresses. From Trump’s wall with Mexico to UK prime minister Theresa May’s red line on immigration to Xi’s artificial islands in the South China Sea, politicians seem to be refurbishing medieval fortresses rather than adopting the fluidness of Frank Gehry.

The political comeback of strong pillars and walls resembles the thickening of the bunkers on the Normandy beach; it resembles an obsession with disappearance, rather than of power and confidence. That said, calling upon leaders to stop building walls and digging new trenches won’t suffice. If we only respond to an accelerating world by reinforcing walls, we risk ending up trapped in our fortresses. However, if we respond to an accelerating world by trying not to order it, we then surrender to chaos.

That is why, rather than bemoaning the end of an idealized global order, we must begin by asking what opportunities would get trapped if we just preserved what needs improving. Will it be the plastic-free ocean? A world without nuclear weapons? A world without extreme poverty? Humanity is not short of big ideas, nor does it lack powerful tools. What it does lack is an architecture for these to scale up for the greater good.

We have no blueprint for such an architecture, but the technology that challenges the old is likely to be at its core. Cities and states won’t disappear, but digital tools will assume many of their mandates. The political functions of urban gateways or territorial borders are already being augmented—and often supplanted—by digital platforms. Firewalls will replace physical walls, as they already have in many parts of the world.

Global leaders must therefore account for the acceleration of matter, energy, and information. From nameless hackers stealing personal data or shutting down power stations to faceless pilots navigating killer drones, today’s conflicts are a continuation and intensification of the pattern bunker historian Virilio described. Digital platforms’ rapidly growing centrality in society naturally makes them a central battleground in the quest for mapping and controlling new sovereign spaces beyond nation states.

We have to rely on new tools and methods to reconcile the need for order with the need for greater freedom and flexibility in an age of acceleration. Clinton was right in that we need a dynamic mix of materials and structures: digital technologies, public-private partnerships, and other new instruments beyond traditional diplomacy. At the same time, she (and an entire generation of globalists) was led astray by the belief that doubling down on new tools and technologies alone could resolve the tension between an encased market and an exposed population.

Great architecture is never obvious, nor is it easy. From the towers of Gaudi’s Sagrada Família to the Guangzhou Opera House of the late Zaha Hadid, it is often awe-inspiring and seemingly defies the laws of physics. The same holds true of our political architecture.

In Davos this year, our discussions will not focus on how to best maintain the architecture of the past, but instead draw a blueprint for one that will work for the future. We must take a hard look at the global structures shaping our lives today. Which political pillars are still carrying weight-bearing loads? Which once are tumbling down? And which structures have become today’s straightjackets? Only then can we develop an architecture that can house the world’s population for decades to come.