What happens when you let people watch what they want, when they want? Netflix tells us that, given a choice, people consume television shows by “binge-watching,” which is the practice of watching back-to-back episodes until your eyes melt. And binge-watching is generally associated with weekends (paywall), suggesting that people save up for their days off. Yet the BBC, whose iPlayer streaming service offers live as well as on-demand shows to viewers, tells a different story (pdf). In Britain, viewing patterns for the iPlayer’s television shows resemble those for traditional TV-viewing—but with a more gradual climb and delayed peak.

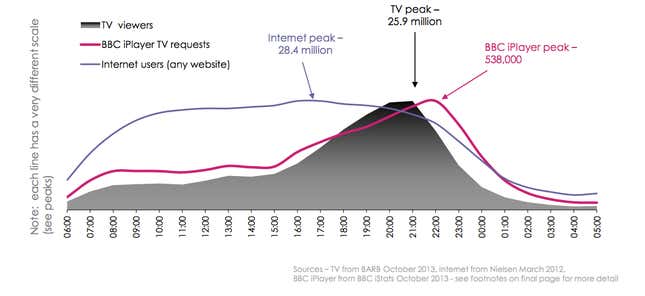

There are some small differences in the way people consume TV on TV and and the way they consume it online. Peak viewing time for television is between 8pm and 9pm, building up from about 6pm and dropping sharply after 9pm. During peak hour, some 26 million Britons plonk themselves in front of their televisions. By contrast, the number of people watching iPlayer starts rising in the late afternoon and hits its highest level around 10pm, also dropping sharply after the peak. (It’s worth noting that the peak on iPlayer is just over half a million people—the BBC is in no danger of losing TV viewers to online ones any time soon.)

One explanation for the later viewing patterns of people streaming shows could be that they’re watching it on their phones or tablets while in bed. Yet the pattern has remained steady for at least two years, even as mobile and tablet use has exploded to 41% of all requests for television content in October 2013 from just 9% in September 2011 (pdf). That suggests that people retain their habits while shifting devices—people were surely taking their laptops to bed in the days before tablets.

Another reason for the slightly later viewing habits online may stem from demographics. While 35% of all British TV viewers are over 55 and only 31% between the ages 16 and 34, this skews younger for iPlayer, with only 22% of users aged over 55 and 37% in the younger age bracket.

Whatever the cause, one thing is clear: What exactly constitutes “prime time” is different online than it is on traditional television. In the case of the BBC, it builds up over a longer period but stays at the peak for a briefer time. As more people watch TV online, they will bring more prime time with them.