A 15-year-old Charles Ardai wanted to interview Isaac Asimov for a magazine article about a new videogame based on the latter’s novel Robots of Dawn. Ardai called up the science-fiction writer’s publisher, Doubleday, and said, “I’d like to interview Isaac Asimov for an article about his new video game.”

“That’s great, but we can’t give out his number,” the Doubleday employee replied.

“No, no, he gave me his phone number,” bluffed Ardai. “But something got spilled on it and I just can’t read it.”

The sympathetic Doubleday employee said, “Oh, well, that’s different,” and obligingly gave the number to the teen.

That’s how the plucky future author, producer, and entrepreneur became a protégé of Isaac Asimov, a bond that would last until the latter’s death in 1992.

Shortly after their meeting, Asimov, who had published an annotated edition of Byron’s Don Juan, gave Ardai a copy of the book with the following signature: “To Charles Ardai, who will be the next me, but I hope less peculiar. Isaac Asimov.”

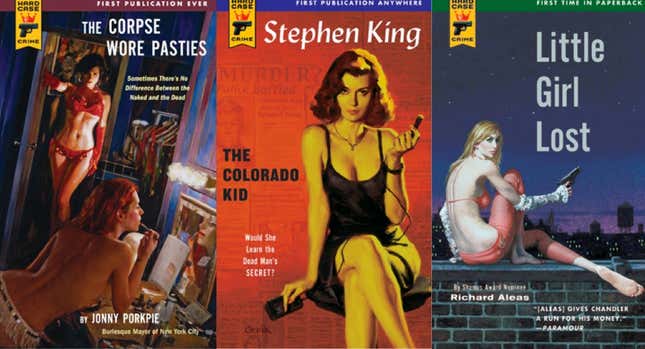

There are similarities between Ardai and Asimov, as they’re both: dyed-in-the-wool New Yorkers; raised in Jewish households; lifelong aficionados of pulp fiction; and breathtakingly polyvalent. Asimov famously boasted that he had published a book in every single major Dewey Decimal category. Ardai has not achieved this feat—yet—but he’s no slouch. Here is a list of his current professional titles: managing director at the DE Shaw group, a global financial firm; chairman of the board of directors for computational chemistry company Schrödinger; founder of Winterfall, which publishes a pulp fiction series called Hard Case Crime; consulting producer on Haven, a weekly American TV show from the science-fiction television channel Syfy. Additionally, he wrote a few of the Havenepisodes, as well as four titles for his book imprint. His short mystery stories have garnered him some of the top accolades in the genre, the Edgar Award and the Shamus Award. He has written four books for his Hard Case Crime imprint (three under pseudonyms, one using his real name).

His debut novel, Little Girl Lost (which he wrote as “Richard Aleas,” an anagram of Charles Ardai), bears this plot summary on the back cover: “Miranda Sugarman was supposed to be in the Midwest, working as an eye doctor. So how did she wind up shot to death on the roof of New York’s seediest strip clup?” The book (released in 2004) was hailed by the Chicago Sun-Times: “Excellent… [A] machine-gun paced debut… Aleas has done a fine job of capturing both the style and the spirit of the classic detective novel.” Ardai’s second novel (again as Aleas), Songs of Innocence (2007), received a starred review from Publisher’s Weekly, which lauded the author’s “crisp prose,” adding, “His powerful conclusion will drop jaws.”

Previously, he was the founder and CEO of Juno, a free email service that he developed in his early years at DE Shaw, which first rose to prominence in the 1990s as an early pioneer of computational finance. (Across the hall, Jeff Bezos was working on the project that would later become Amazon.com.)

Ardai took Juno public in 2003. Finding himself with a font of cash, Ardai decided to embark on a quixotic project: With fellow Shaw employee and novelist Max Phillips, he launched Hard Case Crime, conceived as a publishing imprint that would release hard-boiled detective novels in the tradition of Raymond Chandler. “We decided to do pulp fiction completely straight. No winks, no nudges, no elbow in the reader’s ribs, no bracketing with air quotes, no smirking. We would just do it straight, as if Hard Case Crime were a publisher that started in 1950, had published a book a month ever since, and somehow miraculously was still going.”

Ardai finds modern day neo-noir, such as Quentin Tarantino, to be “glib.” He says, “If you look at classic film noir and crime fiction, you have plenty of genuine suffering. Keep in mind where this came from. These were people writing during the Depression, World War II, in the shadow of Hiroshima, the Holocaust, economic disaster, eventually the McCarthy hearings. This was not a happy century. And it was not a happy time in the century. Which may, in fact, be one of the reasons that there has been a resurgent appetite for noir in the last decade.”

Still, it’s hard not to wonder whether the authors are being a bit tongue-in-cheek, with such titles as The Corpse wore Pasties. Another case in point is my favorite first line from the series, from Max Phillips’ Fade to Blonde: “Well, maybe she wasn’t all that blonde, but it’d be a crime to call hair like that light brown.”

Haven, for which Ardai is consulting producer, is an adaptation one of the books from the Hard Case Crime series, The Colorado Kid. Its author: Stephen King.

The way Ardai got King to write a book for him is redolent of the ingenuity he used as a teen to track down Isaac Asimov.

Ardai said that when launching Hard Case Crime, “I thought it would help our books get more attention if I could get a blurb from Stephen King. I assumed that everyone tried to reach him through his literary agent, so I decided to go a different route: I called his accountant.”

“I might have been thinking that everyone who wanted to contact Stephen King went through his literary agent and I wanted to be different, maybe have a better chance of success. Anyway, I went to the accountant’s office with a package and said, ‘can you pass this on to Stephen King? I’d be very grateful if you did, and I think he might like it.’ It had some samples of what the books would look like and a description of the project along with a request that if he liked it maybe he’d consider writing us a blurb. It could be four words—’These guys know pulp.’ Anything.”

Five months later, King’s literary agent, Chuck Verrill, called Ardai to say that King had received the blurb request through his accountant and wanted to pass on a message to Ardai. “Steve asked me to call you. He wants me to let you know that he does not want to write you a blurb.”

Ardai replied, “That’s completely understandable, thank you for letting me know, that’s very thoughtful—”

But Verrill went on, recalls Ardai, because his sentence wasn’t finished: “…because he would like to write you a book instead.”

Ardai recalls, “Of course I was doing cartwheels on the other end of the phone, but I tried to sound very cool and collected, as if I got a call like this every day of the week. It was an extraordinary moment. And that act of generosity on Stephen King’s part really put us on the map.”

Ardai has personally edited all of the more than 50 books in the series: “It’s not just that I select every book we publish — I personally adjust every line of every book we publish. I adjust the space between the words to make sure every line looks the way I want it to look. I’m talking about the blank space between the words. This is not something I’m supposed to do. This is something I can’t not do. This is how compulsive I am. Left alone, a computer typesetting program will produce ugly, gappy lines…you’ve seen this, when there is too much space between the words in a book. I go in and I fix that manually for every book we publish. It’s insane, it’s ruining my eyes, but I can’t help myself. And on some level I love doing it. It makes me feel like these books are handcrafted artifacts, like a stonemason chipping away with his chisel until it’s just right.”

One might wonder how Ardai’s family copes with his work habits, which he describes as “compulsive.” As it happens, his wife Naomi Novik is pretty busy herself: She is the author of the cult Temeraire series of fantasy books that re-imagines what the Napoleonic wars would have been like if England had intercepted a dragon that had been intended for the French to use as an aerial weapon. Peter Jackson has bought the movie rights.

Ardai and Novik have a twenty-month-old daughter named Evidence. The extended families on both sides are helping to raise the child. Without their help, says Ardai, his workload would be impossible.

Besides, he’s never worried about added responsibilities. “I’ve never liked doing just one thing,” he said.

Quartz asked Ardai for advice for our readers. Here’s what he said: Put on the damn pants.