What Roger Stone’s “Godfather” reference is really about

A fictional character makes an unlikely appearance in the 24-page indictment of Roger Stone, Donald Trump’s long-time friend and consultant: Frank “Frankie Five Angels” Pentangeli, a mobster from the silver screen.

A fictional character makes an unlikely appearance in the 24-page indictment of Roger Stone, Donald Trump’s long-time friend and consultant: Frank “Frankie Five Angels” Pentangeli, a mobster from the silver screen.

Stone, who was arrested Friday (Jan. 25) on charges of obstruction of justice—lying to Congress’s powerful House Intelligence committee, and telling another witness to do the same—may have modeled his actions after pop culture’s most famous rendition of mafia life, Francis Ford Coppola’s trilogy The Godfather, based on the Mario Puzo novel. Rather than tell Congress the truth, Stone encourages one Trump campaign advisor, identified as “Person 2” in the indictment, and believed to be radio personality Randy Credico, to emulate Pentangeli, who appears in The Godfather II. The indictment reads:

On multiple occasions, including on or about December 1, 2017, STONE told Person 2 that Person 2 should do a “Frank Pentangeli” before HPSCI [the House committee] in order to avoid contradicting STONE’s testimony. Frank Pentangeli is a character in the film The Godfather: Part II, which both STONE and Person 2 had discussed, who testifies before a congressional committee and in that testimony claims not to know critical information that he does in fact know.

Who is Frank “Frankie Five Angels” Pentangeli?

Pentangeli runs the New York operations of the Corleone crime family at the center of the trilogy, but falls out with new boss Michael Corleone. He ends up collaborating with law enforcement, telling investigators of Michael’s crimes, including murder.

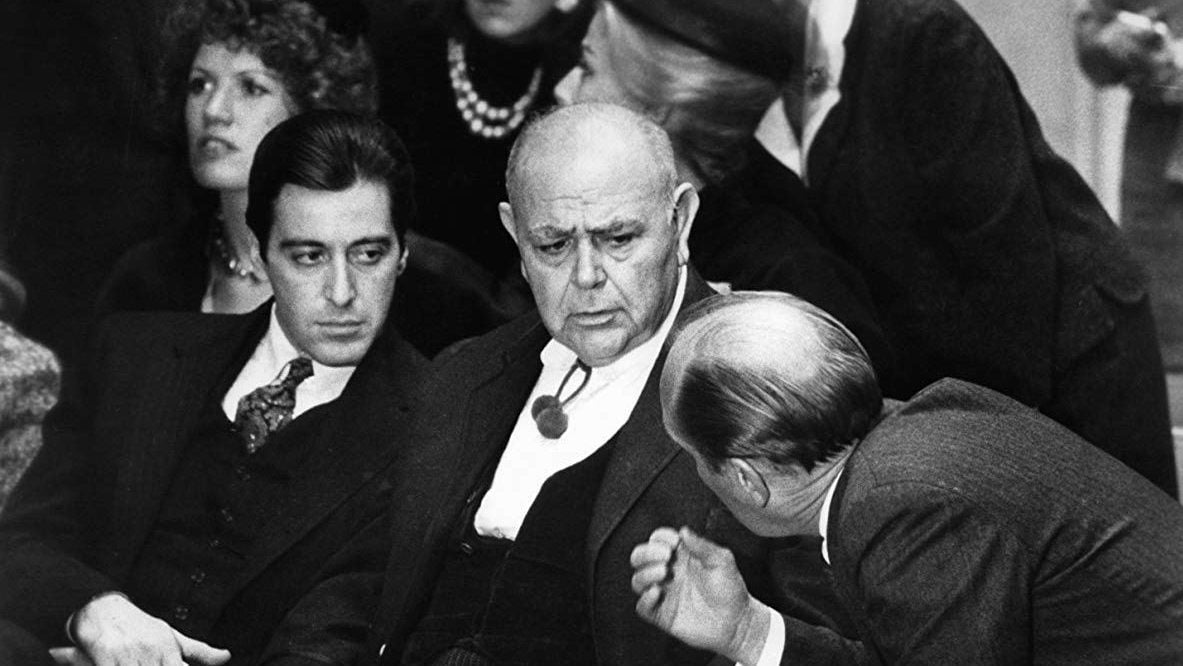

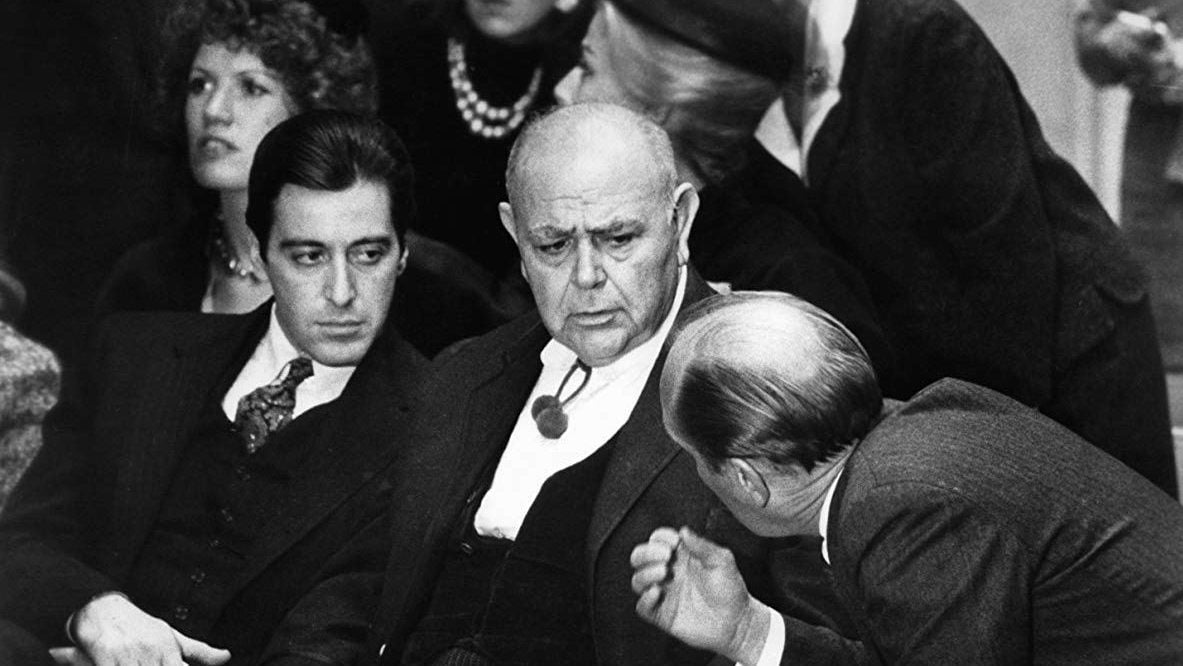

With Pentangeli’s first-person testimony, the US government thinks it finally has a path to prosecute the leader of the powerful crime family. At a public testimony in front of a Senate committee, however, Pentangeli reverses himself after pressure from the family, including the appearance of his Sicilian mobster brother in the audience.

Asked about Corleone, he tells the Congress members “I was in the olive oil business with his father, but that was a long time ago,” denying his own sworn confession. “I made up a bunch of stuff about Michael Corleone, because that was what they wanted,” he says.

The government’s case against Corleone falls apart. Later, Pentangeli, in federal custody, has a discussion with Corleone’s right hand man about how disgraced plotters against the Roman empire would could redeem themselves, and protect their families’ future. The ones who killed themselves, their families were taken care of, Pentangeli muses. “They went home, they sat in a hot bath and opened their veins, and bled to death,” Pentangeli says.

“Don’t worry about anything, Frankie Five Angels,” Tom Hagen says, as a farewell.

And that is just what Pentangeli, forever tainted after collaborating with authorities as a traitor to the mob, does. The character’s final appearance in the film is in a bathtub, bleeding and presumed dead.

Omertà and the laws of crime families

Stone’s proclivity to draw inspiration from cinematographic mobsters—they seem to have influenced his fashion sense as well as conduct—suggests a respect for the supposed moral code they promote. The Pentangeli reference is particularly telling, not because of its gruesome ending, but because it is centered around a core principle of mobster life, the idea of of omertà.

Omertà is an Italian word of uncertain origin. Some think it comes from the Spanish hombre, man, as hombredad “the quality of being a man.” Others identify its etymology in the Italian umiltà, humility. The term is used to describe the complex code of silence that covers all who are involved in a crime or associated with the group who committed it, that dictates they should lie or evade authorities to cover it up. Omertà, in the crime syndicate usage, extends beyond physical accomplices, to anyone who is aware of the crime, or even of the existence of criminals. It includes witnesses, people who may suspect something, victims—they all become perpetrators and victims of the same system.

In the case of Pentangeli, omertà even goes from being an abstract concept to being embodied in one person, his brother, a mobster from Sicily—the motherland, so to speak—who is flown in to remind him that his own family sides with the mob, not against it. The brother embodies omertà, in the shocked, disappointed way he looks at Pentangeli as he prepares to testify to the American authorities. For Frank to testify would be betraying his family, and the criminal system they belong to.

Of the many elements that support a criminal state—or any power that runs parallel to and subverts a lawful government—omertà is arguably the most indispensable. It is what holds Italy’s Cosa Nostra families together, and has protected them for decades. While, at its heart, it is merely silence that results from a combination of guilt and fear, it is also held up as the highest expression of loyalty in any successful criminal entity.

On the flip side, once a critical mass of people inside a system break omertà, then its power suddenly dissolves. The best way to dismantle a criminal organization is to tug crime syndicate members out from under its powerful spell, one by one, until the spell shatters, and the rest of the group follows.

Famed Italian prosecutor Paolo Borsellino, who with colleague and friend Giovanni Falcone was at the forefront of the fight against Cosa Nostra in Sicily in the 1980s and 1990s, was always clear that the main weapon against organized crime was speaking up about it. “Speak about the mafia. Speak about it on the radio, on television, in the newspapers. But talk about it,” he once said. Though he and Falcone were both killed with bombs for their investigations, the cracks they inflicted in the otherwise wall of silence that surrounded the mafia in Sicily led to the arrest of the organization’s leaders. It also empowered the victims of a system that, until then, no one would dare mentioning.

Italy’s prosecutor Alessandra Cerreti discovered that the women in the family were the key, she told the New Yorker, in an article that explains how she and others broke the ’Ndrangheta family crime syndicate.

In a criminal organization structured around family, women had to have a substantial role. Their most important duty was to raise the next generation with an unbending belief in the code of omertà and a violent loathing of outsiders. “Without women performing this role, there would be no ’Ndrangheta,” Cerreti said.

Stone’s recommendation to follow the way of the mob isn’t just a whimsical reference to folklore, or a reference made in jest. It is an expression of the same value system that governs Trump. The president has demonstrated multiple times that he expects others to act according to a code of loyalty to him personally, rather than loyalty to the reputation of the high office that he occupies.

Trump’s reaction to reports that members of his team are collaborating with authorities (Michael Cohen, Michael Flynn, Rick Gates) are suffused with anger, disappointment, and betrayal. Those he perceives as loyal, no matter their alleged violations of the Constitution he’s supposed to uphold, like Paul Manafort, or the man of the hour, Stone, continue to get his praise. After Manafort was found guilty of five counts of tax fraud, a crime that leaches money from the US citizens Trump is supposed to represent, the president tweeted his praise for Manafort:

Stone tipped his hat to omertà outside a Florida courthouse yesterday. “There is no circumstance whatsoever under which I will bear false witness against the president,” he said in an opening statement, announcing he was pleading not guilty. Bearing false witness would be a crime all its own, of course, so that’s an odd declaration. When asked multiple times whether he would cooperate with prosecutors, Stone refused to answer. “I have made it clear I will not testify against the president,” he says again, adding after a pause “because I would have to bear false witness against the president.”