US special counsel Robert Mueller arrested Donald Trump’s longtime friend and ally Roger Stone on Friday (Jan. 25), charging him with obstructing a congressional investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election, witness tampering, and making false statements.

Part of the evidence Mueller used to build his case came from Stone’s own WhatsApp messages, according an indictment (pdf) unsealed on Friday. The 24-page document details Stone’s communications about an entity referred to as “Organization 1,” which the court filing makes clear is WikiLeaks, during the 2016 presidential campaign. According to the indictment, Stone communicated regularly with “senior Trump Campaign officials,” to whom he delivered stolen emails that were surfaced by WikiLeaks, and that he promised would be damaging to Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

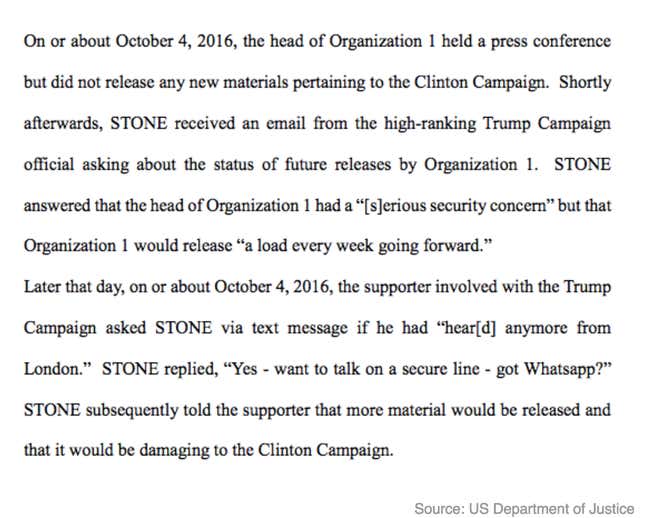

In one exchange, Stone suggests to a contact that they switch their text conversation to a safer channel. “Want to talk on a secure line—got Whatsapp?” he texted.

The indictment goes on to describe messages between Stone and the other party about material that would hurt the Clinton campaign, suggesting investigators working for the special counsel were able to access the WhatsApp exchange.

The messaging service, which is owned by Facebook, is known for its highly secure end-to-end encryption, meaning everything is encrypted before it leaves the user’s phone and decrypted only after it reaches the recipient’s device. Only the sender and receiver, not even WhatsApp itself, can read encrypted messages.

But the system is only as secure as the habits of the people at both ends of the conversation. Experts suggest that the special counsel’s office might have gotten access to Stone’s WhatsApp messages through other avenues.

A friend in London

The exchange Stone wanted to continue on WhatsApp appears to be related to an impending WikiLeaks dump.

At the beginning of October, Stone texted a radio host referred to in the indictment as “Person 2” and described as an intermediary between Stone and the “head of Organization 1,” who is not identified in the indictment but is described as being located “at all times in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London,” where WikiLeaks chief Julian Assange was living at the time. Stone said to expect “big news Wednesday . . . now pretend u don’t know me . . . Hillary’s campaign will die this week.”

Two days later, Stone also messaged a “supporter involved with the Trump campaign,” according to the indictment. “Spoke to my friend in London last night,” it says, presumably referring to a direct exchange with Assange. ‘The payload is still coming.”

On Oct. 4, the unidentified Trump “supporter” sent Stone a text message asking if he had “hear[d] anymore from London.” After that message, they switched to WhatsApp.

Following the first email dump by WikiLeaks on Oct. 7, an “associate” of a ”high-ranking Trump Campaign official,” said to be Steve Bannon, sent a text message to Stone that read ‘well done,'” the indictment reveals.

Overestimating WhatsApp security

WhatsApp uses a well-regarded privacy tool, the Signal Protocol, to encrypt its users messages. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital rights group based in San Francisco, calls it “best-in-breed for encrypted messaging.”

While a search warrant could entitle authorities to search a person’s phone, or force an internet or mobile service provider to hand over whatever might be stored on their networks, WhatsApp only lets encrypted messages pass through its servers. Since it doesn’t store them there, even if authorities subpoenaed WhatsApp for the data, there would be nothing to see.

But people are often unaware that they have their device set to automatically back up all of their data, which could include their WhatsApp conversations, says Rebecca Herold, a cybersecurity consultant and president of Simbus360, which makes security software. WhatsApp can also be set to automatically back up a user’s chats. Messages can be stored in multiple places, including a person’s iCloud account, Google Drive, Dropbox, or on their home computer or corporate network. Encryption can’t protect people if they’re sloppy with the way they handle their data, says Herold. “People need to understand that you can’t just have this one magic application that can control the entire environment within which it’s being used,” she adds.

Herold points to what Stone might have done with those messages at some other point in time, including the possibility he incorporated them into other documents or even a screen grab. “If I was doing the technical investigation on this, I would start by looking at those things,” she says. “It’s beyond the scope of the capabilities of WhatsApp, it has to do with how the users at the endpoints are handling their information.”

Indeed, Mueller also used WhatsApp messages as evidence to indict Trump’s former campaign chief, Paul Manafort. Investigators were able to read communications Manafort allegedly tried to hide by sending them via WhatsApp and Telegram, another secure messaging service. Mueller’s team indicated that they accessed those messages through Manafort’s iCloud account, where they had been backed up.

Trust is key

Technical ineptitude isn’t investigators’ only recourse. People on either end of encrypted conversations can also be squeezed to give their exchanges up.

“How secure is WhatsApp, really? Very secure,” EFF researcher Gennie Gebhart says. “The key is to ensure that you and anyone you’re chatting with is not backing up to Apple (for iPhone users) or Google (for Android users) servers. And, of course, ensure that you trust that people you are chatting with.”

Mark Sangster, chief security strategist at cybersecurity firm eSentire, compared the Stone situation to that of a recorded phone conversation. “Law enforcement may not have tapped the line, but perhaps someone else involved in the investigation, or under observation, recorded it and investigators got it from them,” Sangster says, adding that information is vulnerable “anytime it gets outside systems that are under an organization’s control.”

Rudolph Giuliani, president Trump’s lead attorney, told the Washington Post that he spoke with an unruffled Trump about Stone’s indictment. The president is “safe,” he said.

Read the full indictment here:

With additional reporting by Hanna Kozlowska and Mike Murphy.

This article has been updated with additional description and a link to WhatsApp’s backup settings