Not a month after a breakthrough in nuclear negotiations with Iran, US legislators are pushing for a fresh round of sanctions. The bill will punish Iran should it flout the nuclear agreement’s six-month deadline for curbing uranium enrichment and allowing more inspections.

The White House argues this makes the US look like it negotiated in bad faith. It also risks discrediting Hassan Rouhani, Iran’s newly elected—and relatively moderate—president, says journalist Peter Beinart.

But there will be more casualties than just Obama’s and Rouhani’s reputations. As in, non-metaphorical ones. Six years of sanctions have throttled Iran’s supply of essential drugs, causing an acute shortage of things like antibiotics and vaccines, as well more advanced drugs, as this article in Nature highlights.

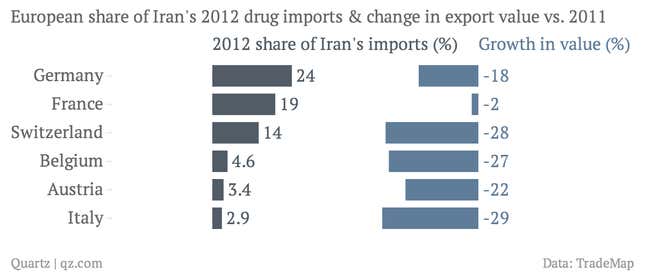

The chart below shows Iran’s top European pharmaceutical trading partners. Despite steep drops in drug exports to Iran, these still accounted for more than two-thirds of its imported drugs.

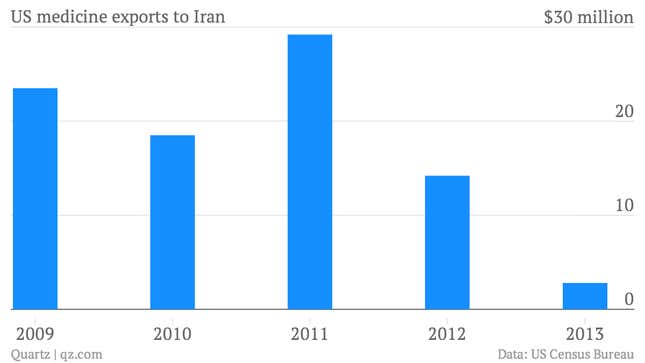

Here’s a look at how US exports of medicines have trended:

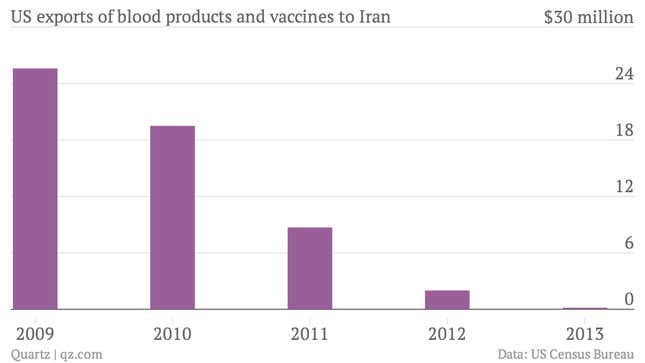

US exports of vaccines and blood products have dropped even more sharply. A lack of childhood vaccines has endangered infants. Hemophiliacs, kidney dialysis patients, and those undergoing transplant surgery face life-threatening shortages of blood products as well, as the Washington Post reported last year. It’s also grim news for a country that has an unusually high incidence of thalassemia (pdf), a particularly nasty form of anemia, for which blood transfusions are the main treatment.

This isn’t supposed to happen. As former US secretary of state Hillary Clinton explained in 2010, the “goal [of sanctions] is to pressure the Iranian government… without contributing to the suffering of ordinary [Iranians] who deserve better than what they are currently receiving.” But the humanitarian loopholes in US, EU and UN sanctions aren’t working the way Clinton described.

Banking is a big reason. The international banks that handle the payments for drug firms that want to sell medicine to Iran risk fines of more than $1 billion if they make a mistake in the forest of paperwork required to approve humanitarian trade, according to a recent report by the Woodrow Wilson Center (pdf, p.4). Both foreign companies and Iranian pharmaceutical importers face similar funding troubles in Europe, says the report.

It also just looks bad to trade with a pariah regime. A new US policy that requires US-listed companies to disclose any Iran revenue in quarterly statements increases the risk of stigma. Leading pharmaceutical firms including Sanofi Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Novartis reported Iran sales in 2012; through the first three quarters of 2013, none has (though their annual reports may be more conclusive).

What might Iranians be missing as a result? A few examples include €185,000 and €1.4 million ($250,000 and $1.9 million), respectively, worth of flu and rabies vaccines (p.266) that Novartis sold in 2012. Or Novo Nordisk’s insulin and hemophilia products.

A clause in November’s agreement clears foreign and Iranian banks to facilitate trade in medical items. That’s cause for optimism, though as Nature reports, public health experts worry that implementation may be hard. And if US lawmakers get their way, that window could very soon be shut.