Is the yuan going global, or just masking more shady Chinese banking?

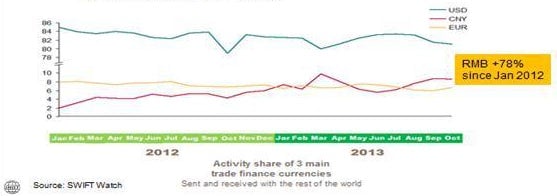

An obscure trade report about China is raising eyebrows about the swift rise of the country’s currency. After accounting for a mere 1.9% of financing for global trade in January 2012, the yuan now makes up a whopping 8.7% in October 2013, reported Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

An obscure trade report about China is raising eyebrows about the swift rise of the country’s currency. After accounting for a mere 1.9% of financing for global trade in January 2012, the yuan now makes up a whopping 8.7% in October 2013, reported Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

But the yuan isn’t nearly as powerful globally as some pundits might have you believe. Here’s why:

At most, around 15% of China’s trade (paywall) is currently settled in yuan. Either a big chunk of global trade—more than half—would need to come from China for 8.7% of global trade to be settled in yuan, or companies outside China would need to be settling trade in yuan, which doesn’t square with the currency’s inaccessibility.

So what can explain the funny numbers?

Jake Van der Kamp at South China Morning Post has an answer. Around 80% of global trade is conducted in open terms, meaning directly between two parties. SWIFT only counts the other 20%, which is traded through letters of credit, a payment guarantee routed through banks. ”Thus the only thing that the SWIFT ranking of global trade indicates is that exporters and importers who settle their accounts in yuan do not have that same high level of trust in each other that is enjoyed by most other traders,” he writes.

But that still doesn’t explain why the 20% that SWIFT does measure, Chinese issuance of letters of credit (LCs), has surged since January 2012 relative to the rest of the world:

The simplest answer is that LCs are a popular investment tool among Chinese investors.

This activity involves using faked import orders to take out LCs at banks—which is essentially a form of borrowing. The rate on a six-month LC is about 2.5%, according to a note last summer by Anne Stevenson-Yang of J Capital Research in Beijing—much cheaper than that on a loan. The investor then cashes in the LC, investing in wealth management products (more on those here) and earning a much higher return than that 2.5% before having to pay up.

Banks are keen on the trade—and are therefore willing to lend at such low rates—because the LC doesn’t count as a loan and therefore doesn’t require a commensurate deposit.

Credit issued through instruments like LCs isn’t captured in China’s official loan tallies, Stevenson-Yang recently told Quartz. That’s why the government cracked down on fake trade activity in May, inadvertently causing the liquidity freeze in June. Judging by the uptick in LCs, the government has apparently loosened the reins since then. (That said, SWIFT shows LC issuance slowing a bit in October.)

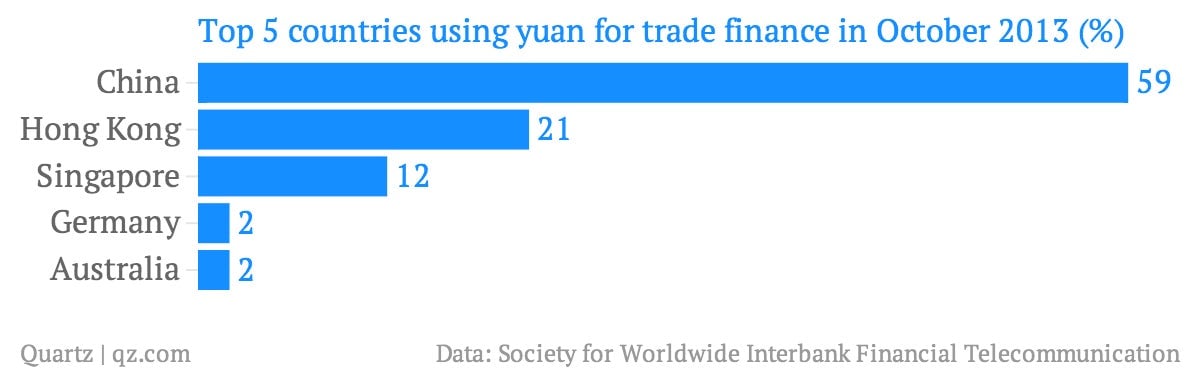

Investors are also using LCs to bring cash from offshore trading centers like Hong Kong and Singapore onto the mainland. That explains why offshore trading centers show up as hotbeds for yuan-denominated trade finance:

So is the yuan internationalizing at a brisk clip? Probably not. Are Chinese banks still spewing tens of billions of yuan in credit disguised as trade finance each month? SWIFT’s report certainly makes it look that way.