There’s so much money gushing out of West Texas these days that even a deadly highway doesn’t keep people away. The fracking boom is shredding a key stretch of asphalt that runs from Pecos—site of the world’s first rodeo—through a former ghost town and into New Mexico. But even as the carnage piles up, businesses are blossoming like cactus along US Highway 285.

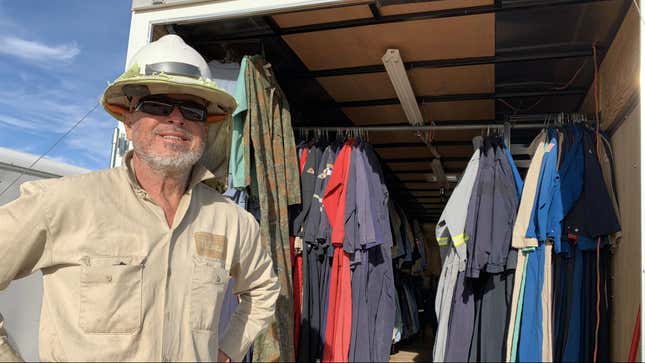

John Cantu, a gray haired 63-year-old born in Northern Mexico, is one of these entrepreneurs. One look at me and he knew my sizes exactly: 32-inch waist, 32-inch inseam, medium shirt.

I didn’t expect that kind of sartorial expertise from a guy selling clothes by the side of the road on the edge of the Chihuahuan Desert. While Cantu showed me the thousands of pieces of fire-resistant clothes in his trailer, trucks carrying sand, water, and hulking fracking equipment rumbled by on US 285.

Cantu got the idea a few years ago when he was buying industrial clothes from rag houses—warehouses that buy thousand-pound bales of used clothing—to sell in Louisiana. After a while, customers started asking him for fire-resistant clothing, known as FR in the business.

Cantu had never heard of the garb, which is sometimes made from synthetic fibers like non-combustible modacrylic. He discovered that demand for FR was coming from the oil fields in West Texas, where it’s standard issue for workers. He bought a load of inventory to make a trial run near Pecos, and his FR quickly sold out, like shiny belt buckles at a rodeo.

“I said, ‘this is it!’” Cantu, also known these days as FR John, told me. “I wish I had done it sooner.”

Now, the self-described tree hugger is making a killing from the petroleum industry.

The people, mostly men, working on the fracking rigs often put in 14-hour days, for two weeks on and then one week off. That makes simply driving to work dangerous, amid the gauntlet of exhausted drivers and heavy trucks. Newspapers have dubbed US 285 the “Death Highway.”

And then there’s the work itself. At truck stops, you hear stories about men who get crushed by machinery or poisoned by hydrogen sulfide gas. Workers end up covered in oil, mud, and drilling fluids. The lines at laundromats can stretch for hours. Some men throw their clothes away instead of wash them.

“The poor guys, they work so much,” Cantu said. After a moment, he added: “This oil field would not run without the Mexican nationals, God bless their souls. The majority doing the hard work are Mexican nationals. Are they legal? Do they have their paper work?”

Death Highway

I grew up close by, in a town called Fort Stockton, but I can’t recall driving what’s now the most treacherous section of US 285. Until recently, there was almost nothing there, and what was there—an expanse of desert dotted with rusting industrial equipment—resembled something from a Mad Max film. These days, the road is disintegrating from the daily bombardment of truck traffic. When someone gets a job driving US 285, their families try to talk them out of it. But that’s hard to do when there’s a pile of money to be made.

US 285 is just one symptom of the West Texas fracking boom, which is so ferocious the local infrastructure—from schools to hotels, restaurants, and roads—can’t keep up with it. Vehicle crashes in Reeves County, where a key stretch of the highway is located, have risen 300% in the past decade as the oil frenzy revs up.

The trick to avoid the craters in the road, a local who works in oilfield construction told me, is to memorize where the holes are. “It’s still hard to avoid them at night,” he admitted. “It’s not the only road in West Texas like this.”

That was something I heard from a lot of truckers, like Miguel Saucedo. We met at a truck stop, where he vented about inexperienced drivers and ate a Tupperware lunch he brought from home.

Saucedo has worked in West Texas for seven years, some of them on fracking wells. Now, he does “hot shotting”—which means he pulls a 40-foot trailer that can carry 60,000 pounds. His job is to be available to haul in, at a moment’s notice, whatever is needed for a rig to keep running, which can be anything from pipe to directional drilling tools. The biggest problem with his job is the newbie drivers.

“They’ve got their foot up on the dashboard!” he said. “They forget they have a trailer in back. Big trucks, they don’t brake as fast.”

Praying cowboy stickers

The largely empty landscape around US 285 is scattered with fracking rig equipment and supplies, truck stops, and long rows of temporary housing called “man camps.” Fracking for oil brings up natural gas, another valuable commodity, but the region, for now, lacks the pipelines to carry the gas to market. Instead, it burns off in giant flares like birthday candles.

West Texas booms every few decades during an oil rush, sucking in fortune-seekers with it. Many of them are young men who work on the fracking rigs, making as much as $100,000 a year, or even more, but around the fields there are also armies of truck drivers, man-camp builders, truck stop workers, and other hardy entrepreneurs.

In a dirt pull-off next to a gas station, I saw a school bus that had been converted to a cafeteria selling tamales. Nearby, there was a baffling RV flying pro-Trump and “Don’t Tread on Me” flags that was almost completely covered in stickers (Confederate flags and the “Make America Great Again” slogan were prominent).

I figured it must be the work of a compulsive (and almost certainly armed) traveling preacher of nationalism and far-right politics. But it turned out the stickers were for sale. The heavy-smoking proprietor was a jolly man with a green cartoon martian tattooed on his scalp. He said the praying-cowboy sticker was probably the most popular one on offer.

Pilot Flying J

Apart from an actual fracking rig, the best place to get a feel for the boom is at a truck stop. Men, as often as not speaking Spanish, line up in coveralls with corporate logos to buy food. The area lacks just about everything—Orla doesn’t have a proper supermarket, a church, or even a bar—but it does have an incredibly well-run, polished, Pilot Flying J truck stop that acts as a grocery store, restaurant, hangout, and coffee shop for thousands of workers. It runs out of breakfast food by 7 a.m. because men start streaming in at 4 a.m. During the day, you can buy a salad or a meatloaf and listen to a speaker in the ceiling that announces when a shower becomes available.

Flying J, like the fracking rigs, has to import employees, many of whom are women, and put them up in modular housing. It’s a tough sell, as there isn’t much to do in Orla when you’re not working. The labor ends up costing about 25% more than usual, but it’s worth it because the company says those locations are among Pilot Flying J’s highest-volume outposts.

Don’t call it a “man camp”

West Texas is far short of the number of workers needed to keep up with the demand for truck drivers and roughneck workers on the oil rigs. Employees are imported from other parts of Texas, other states, and other countries. Sometimes they stay in hotels, where rates have shot up to $300 a night or higher, or companies house them in one of the fleets of trailers—the man camps—that have been trucked in to expand the housing stock.

At some camps, rig workers putting in 14-hour (or more) days will share a room, swapping when one shift ends and the other begins. The official population in Pecos, Texas, is around 9,000. But the workers brought in to handle the wells have doubled that, according to some estimates. “This oil boom, it runs over these towns like a tsunami,” said Ralph McIngvale, a partner at Permian Lodging.

I visited a Permian Lodging camp that’s open to the public for lunch. Miki Bryce, a polite sales assistant with the air of a concierge, greeted me at the door even though I was unannounced. She insisted on treating me to a late lunch, and then also insisted that any article mentioning Permian Lodging shouldn’t refer to it as a man camp. The owners took issue with a Bloomberg article that had referred to it as such. “We are an exception,” she said. “It’s a lodge.”

Bryce said Permian Lodging was a cut above the other temporary housing options, with better chefs, gel-topped extra-large mattresses, a gym, high thread-count sheets, and a movie theater. When I visited, men were playing pool and televisions were playing football in the cafeteria, which was serving steak that day. “I hope you’re a carnivore,” Bryce said.

An ocean of oil

Texas is so rich in oil that it used to bubble up to the surface on its own. West Texas and part of New Mexico are home to the Permian Basin, a particularly bountiful, 75,000-square mile expanse that was a shallow seaway some 850 million to 1.3 billion years ago, where algae and prehistoric life became the basis of what’s now an ocean of underground oil.

Even after almost 100 years of drilling and extraction, the Permian is one of the top producing oil fields in the world, now pumping out around 4.1 million barrels per day. One of the keys to the Texas resurgence, of course, is hydraulic fracturing—that is, fracking—which traces its roots to the days of Standard Oil, the monopoly established by John Rockefeller in 1870.

These days, teams drill a miles-deep deep vertical hole in the ground, and then rotate the bit and chew horizontally through another mile or so of rock. Engineers then concoct a customized cocktail of water, sand, and chemicals to blast into the underground formations under high pressure, releasing trapped oil and gas.

The Permian is a major reason why America is now the world’s biggest oil producer: It accounts for 459 of the 990 rigs operating in the US, according to Baker Hughes, an oilfield services company. That’s why Chevron and Occidental sparred over Anadarko Petroleum this year, a battle that Occidental chief executive Vicki Hollub won by splashing out $38 billion, winning her company Anadarko’s prized assets in the Permian.

About 60 of the Permian Basin’s oil rigs are concentrated in Reeves county, where Pecos and Orla are located. It’s one of the few ways that young people, mostly men, with strong arms can still make a lot of money without a college education.

On US 285, traffic flows constantly. More lanes, which are being built by the highway department, are desperately needed. At its busiest, the line of trucks runs interrupted, day and night. “It’s like Los Angeles at rush hour,” said Shameek Konar, chief strategy officer at Flying J, the truck stop chain with the immensely popular outpost in Orla.

Truck drivers told me they were grateful for a highway patrol crackdown, forcing drivers to go slower, and stopping them from trying to pass too many cars on the road at once. But shutting down the road entirely until it can be properly repaired seems out of the question. There’s just too much money at stake.

One afternoon, I was driving down US 285 and Trump was on the radio. He was delivering his oft-repeated diatribe about crime and drugs flowing across the southern border, along with immigrants. It made me wonder how many undocumented workers were in the oil fields around me.

Texas relies heavily on undocumented labor for farming, according to the Pew Research Center, but the data suggests it’s far less common in the fracking industry. Jeffrey Passel, a senior researcher at Pew, estimates that there may be around 20,000 unauthorized immigrants working in the Texas oil and gas industry. If accurate, that would represent around 5% of workers in fracking.

That number is a lot smaller than the guesses I heard from everyone I interviewed, some of whom talked about rigs where all operations are conducted in Spanish. One possibility is that West Texas workers vastly overestimate the number of undocumented immigrants on their crews. Multibillion-dollar energy companies, after all, have a lot to lose by using illegal employment practices. The other possibility is that the undocumented workers are obscured within layers of subcontracting and aren’t reflected in surveys.

Boom and bust

West Texans know the boom won’t last forever. They’ve been through it plenty of times before. They’re making money while the getting is good.

RF John is plotting an expansion. He plans to sell food next door to his clothing trailer. With his wife’s help, he said he wants to run the food business 24 hours a day. He may also get an account with Square so he can accept card payments, letting customers swipe their corporate credit cards. It’s not because he’s worried about getting robbed—he says even the “dope fiends” are making too much money to bother a guy in a trailer stuffed with cash.

“It’s going to be exciting,” he said. “I’m cleaning up.”

—With additional reporting from Amanda Shendruk