What happens when an irresistible Space Force meets an immovable Congress? Compromise.

When Donald Trump interrupted a satellite traffic management announcement in 2018 to order the top-ranking military officer present to create a sixth branch of the military for all things space, he insisted on a ”separate but equal” force.

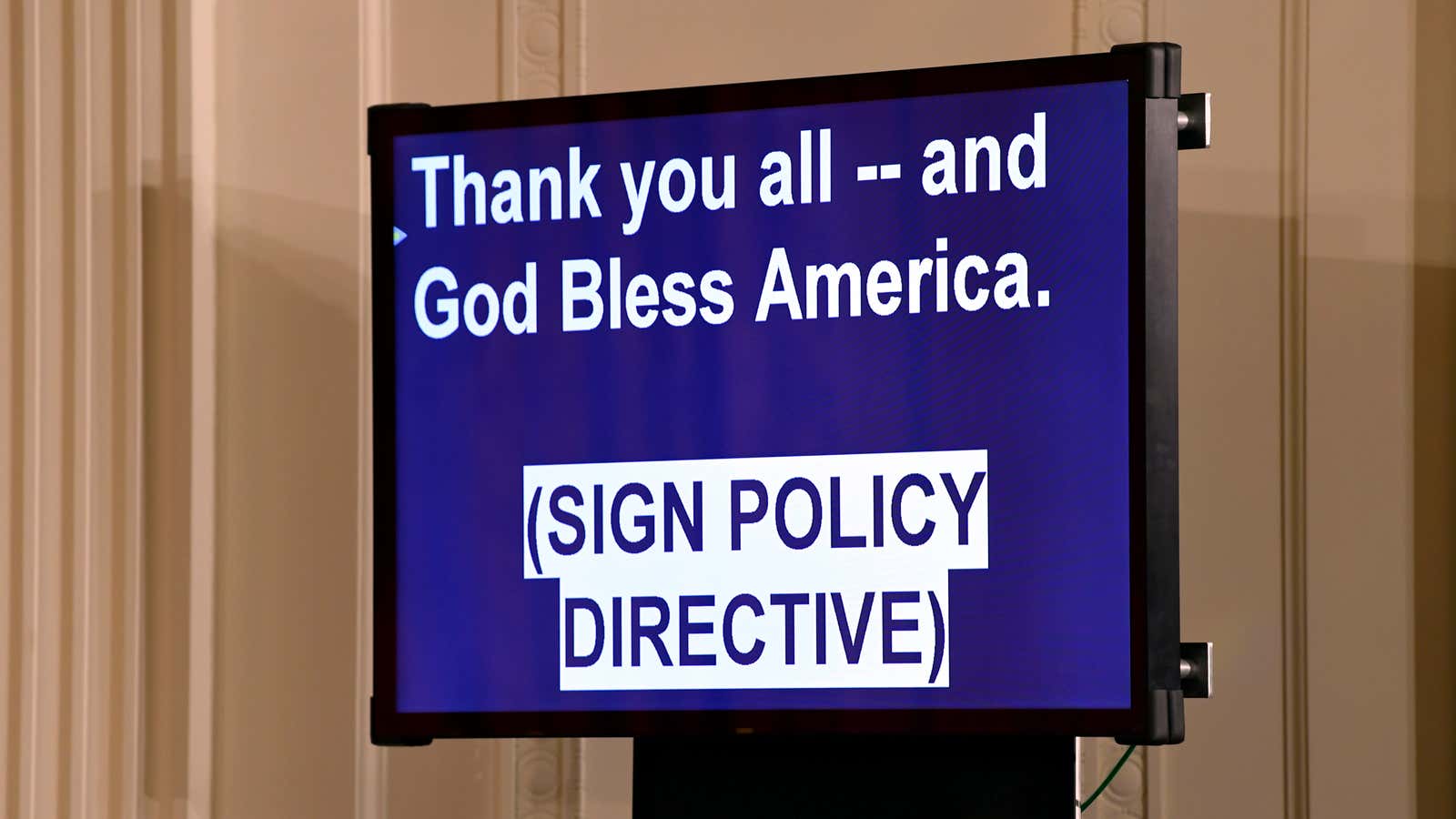

Today (Feb.19), Trump signed Space Policy Directive Four in a closed-door ceremony, for the first time outlining what he is asking Congress to do. What he now seeks is not a brand-new institution but a reorganization of military space operations underneath the aegis of the US Air Force, akin to the Marine Corps relationship with the US Navy.

The directive tasks acting defense secretary Patrick Shanahan to propose this plan to lawmakers: Consolidate all military space activity to be under the command of a general officer—the chief of staff of the Space Force—and a civilian undersecretary of the Air Force.

The Space Force will not include space-focused spy agencies like the National Reconnaissance Office or civilian space agencies like NASA or NOAA.

The White House calls this a step toward a sixth branch of the US military. Lawmakers have been skeptical of that vision—and its attendant costs—in the past. The more circumspect starting point is likely to give the proposal a better shot in Congress, where the new Democratic majority in the House is likely to question every assumption coming from the administration.

Re-organizing the military space capabilities currently scattered among the various service branches is seen by military experts and lawmakers as worth doing. Figuring out a manageable consensus on how to do so has proven elusive.

The argument for a single point of responsibility has less to do with visions of space warfare and more to do with ensuring service members have career paths that give them deep expertise and that billions of dollars in spending on military spacecraft are directed as efficiently as possible.

SPD-4 suggests the Space Force could include some 35,800 service members in the Air Force, Army and Navy who maintain and operate satellites that provide communications and intelligence for the military at a total cost of some $13.5 billion a year. Setting up the agency could cost between $3 billion and $13 billion over the next five years, according to wide-ranging US Air Force estimates.

The next step for this proposal will be planning for the 2020 fiscal year, which begins in October. Increased spending on military space, particularly around satellites designed to spot nuclear weapons before they are launched, is already part of that conversation.