As Florida governor Rick Scott likes to boast, everyday 500 people move to his state. Its population is set to hit 20 million in 2016, surpassing New York to become America’s third most populous state (after California and Texas). That’s great news for a state with no income tax. With most of its budget coming from property and sales taxes, the best way to earn revenue is to attract more Floridans.

Just don’t tell them about this:

That’s a sinkhole—what happens when brittle and porous sediment collapses. Sometimes whatever’s on top sinks into the ground. Other times the ground gives way entirely, forming earthy maws up to 100 feet (30.5 meters) deep—big enough to swallow a boat, a pool and parts of two homes. In February, a sinkhole killed a man when it opened beneath his bedroom. Here’s footage of a sinkhole that sucked up a resort in August:

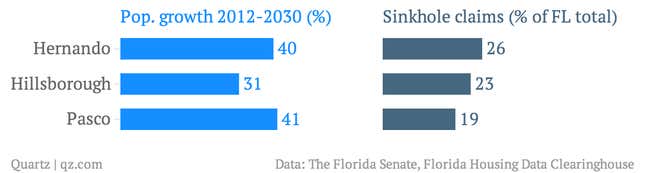

Every year, hundreds of new sinkholes dot Florida’s terrain. Though they’re divided on whether sinkhole incidence is increasing, scientists generally agree that Florida’s surging population means more people are encountering sinkholes. Either way, expect to be hearing a lot more about them. Scarce land in southern Florida is driving the state’s new masses straight for what’s called “Sinkhole Alley“: three counties around Tampa, in Florida’s central swath. From 2012 to 2030, populations in Hernando, Hillsborough and Pasco counties—which accounted for a combined 68% of sinkhole insurance claims (pdf, p.17) in 2010—are set to grow way faster than Florida’s overall 22% increase.

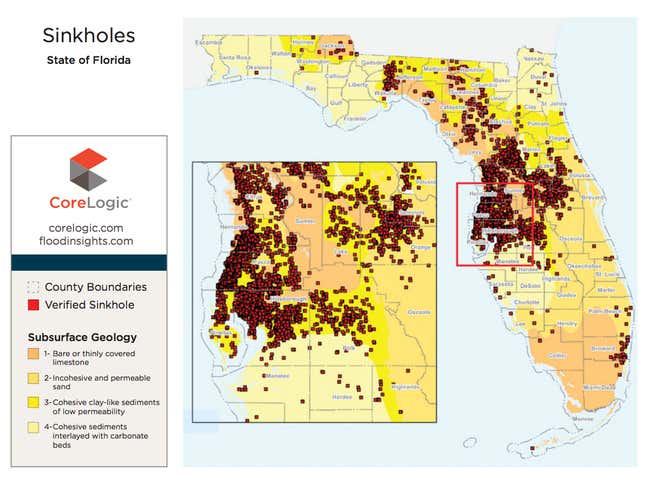

Not that sinkholes only happen in Sinkhole Alley. (To the question of whether any area in Florida is safe from sinkholes, the state website says, “Technically, no.”)

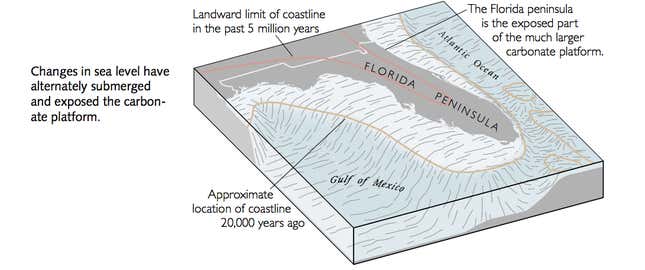

For the statewide nature of its sinkhole menace, Florida can thank its fragile limestone bedrock and its coastal location. Over time, rain and layers of sand from prehistoric beaches erode that rock, creating underground caves.

When the top layer of ground falls into a cave—voilà, sinkhole. Dramatic changes in the land’s weight distribution can cause that to happen. Some factors, such as water from heavy storms, are natural. In 2010, nearly 200 sinkholes formed in Hernando County after Tropical Storm Debbie. Drought, too: Water drained without replenishment hollows out wells.

But many of the causes stem more directly from humans. Winter sinkholes often have something to do with Florida’s massive citrus and strawberry industries (pdf, p.134). To prevent frost damage, growers pump warm water onto crops, emptying wells and shifting water weight to the surface. Then there’s paving over ground, which prevents the ground from absorbing water evenly. Plus, Floridans generate 50% more waste (pdf, p.62) than the national average.

They also simply use too much water, says the US Geological Survey. Yet the Florida government has steadily slashed funding for water management. That’s not exactly surprising. Water conservation efforts require more taxes. And that could deter the 500-strong daily influx of people hoping to make Florida their new home.