What the study of animal emotions shows us about being human

The Greek philosopher Xenophanes came up with the word “anthropomorphism,” meaning “human form” in the fifth century BC to protest the poetry of Homer, which described gods with human shapes and qualities. Xenophanes joked that if horses could draw their gods, those deities would look equestrian. And ever since then, “anthropomorphism” has been used derisively.

The Greek philosopher Xenophanes came up with the word “anthropomorphism,” meaning “human form” in the fifth century BC to protest the poetry of Homer, which described gods with human shapes and qualities. Xenophanes joked that if horses could draw their gods, those deities would look equestrian. And ever since then, “anthropomorphism” has been used derisively.

Today, the term refers more broadly to a human tendency to attribute our own traits and experiences to other creatures. And many scientists still resist this tendency, arguing that it’s impossible for animals to have inner lives that resemble ours.

Primatologist Frans de Waal has coined a term for the rejection of anthropomorphism, dubbing it “anthropodenial.” In his new book, Mama’s Last Hug, he argues that anthropodenial—discounting the complexity of other animals— persists because we’ve been able to justify a lot of cruel behavior by claiming that animals don’t really feel like we do.

Yet scientists are increasingly finding that there’s little distinction between the way animals and humans feel and behave—or, rather, that there are similarities and that animals also have feelings. They have a consciousness. They have cognition.

Our brains are similarly structured, with the same neurotransmitters. The differences between a fish and a person’s physicality and environment account for the fact that our inner lives aren’t identical—but just because a fish lives in water and doesn’t seem to grieve like you and me doesn’t mean the fish has no mental life or self-awareness, or sense of finality.

De Waal thinks anthropomorphism is positive. It seems to be a more correct understanding of animals. Of course we differ in details, but he has spent decades observing the behavior of primates, and it’s taught him quite a bit about humanity in the process. In his latest book, he explores the changing science of animal cognition and the evidence that people and creatures have an awful lot in common, writing:

Anthropomorphism is not nearly as bad as people think. With species like great apes, it is in fact logical. Evolutionary theory almost dictates it, given that we know apes as anthropoids, which means ‘human-like’… The simplest, most parsimonious view is that if two related species act similarly under similar circumstances, they must be similarly motivated.

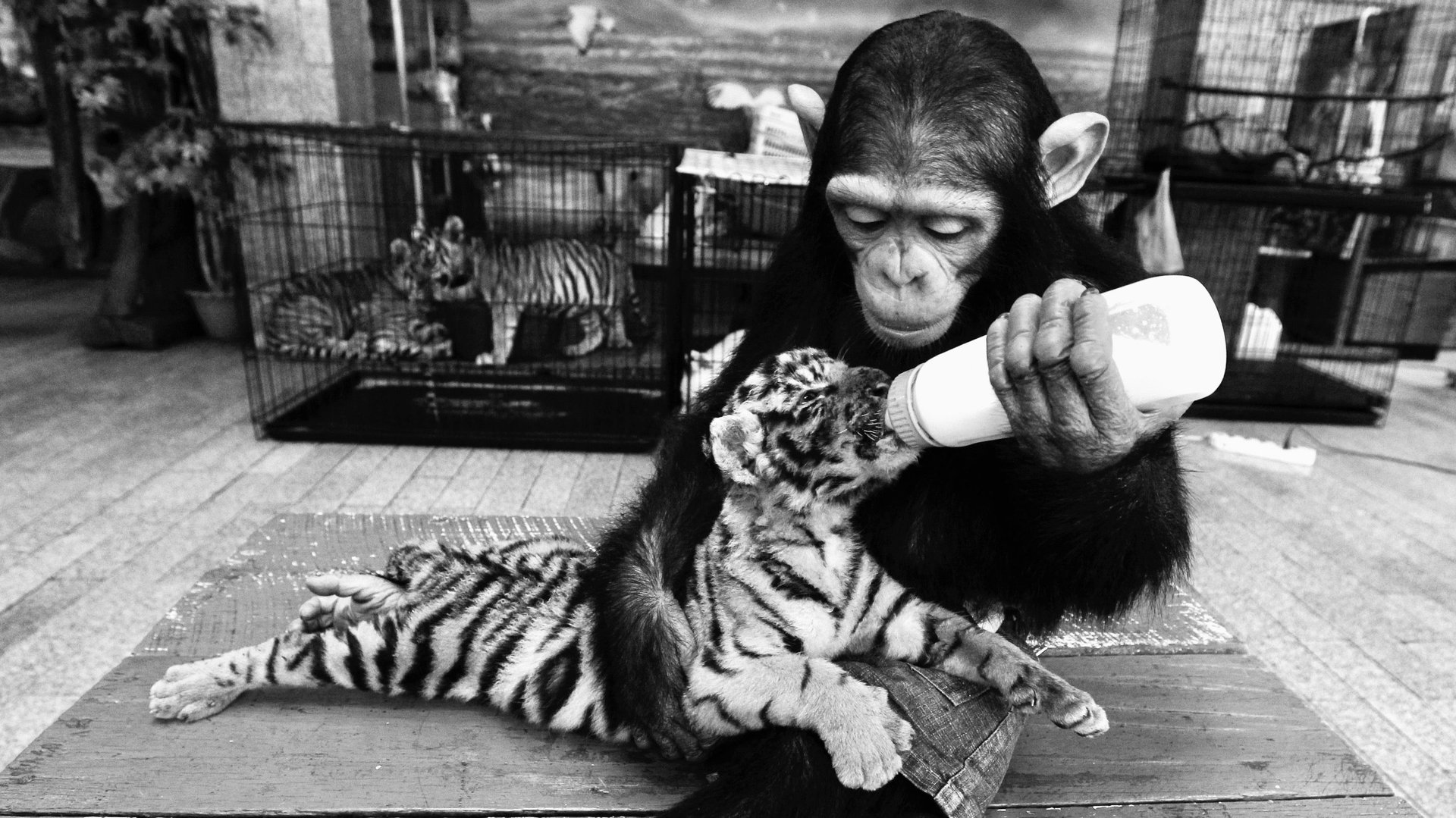

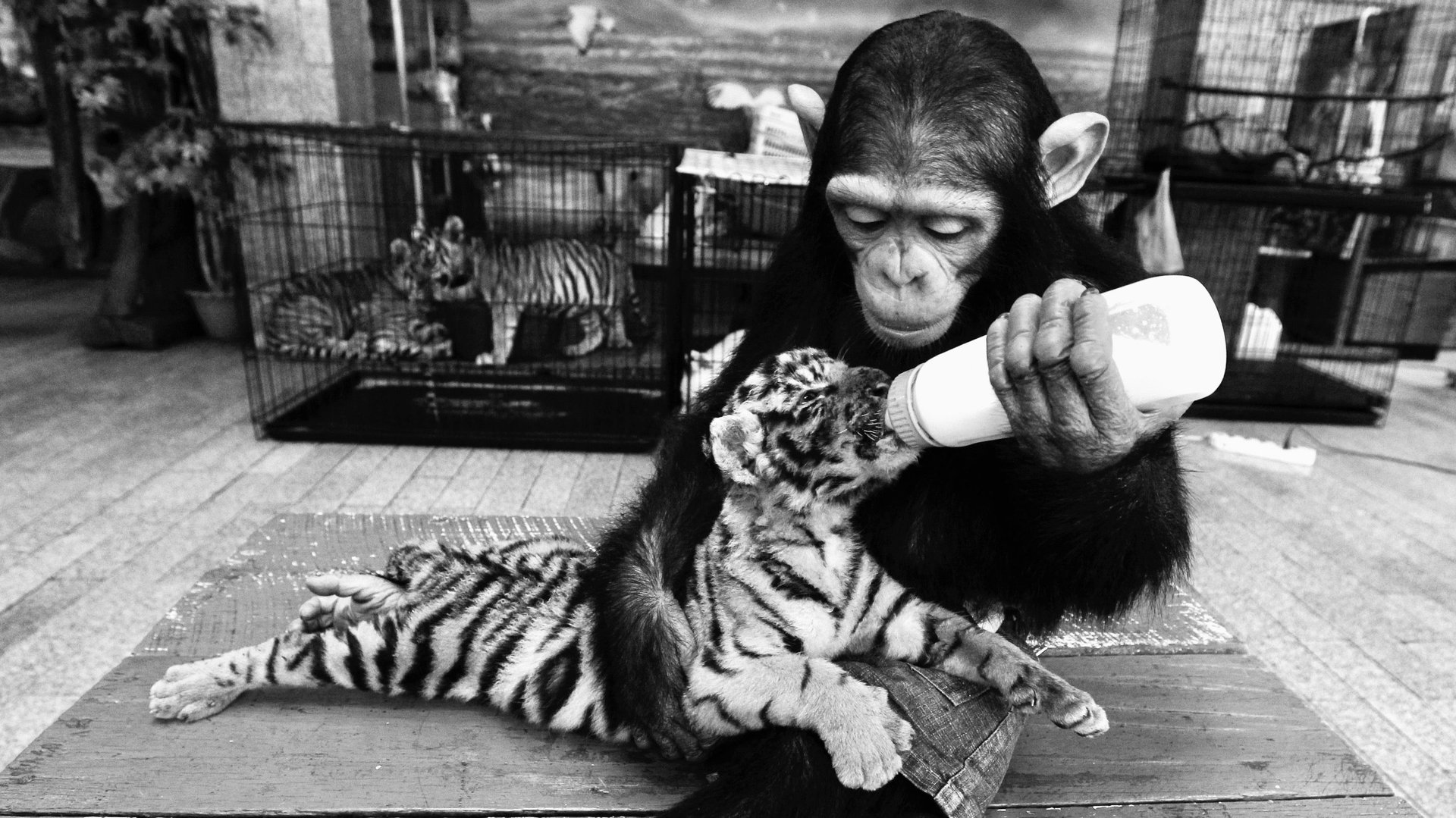

And we do act much like primates. De Waal tells the story of Kuif, a female chimpanzee who didn’t much care for him at first. Kuif didn’t take to the primatologist until he did her a kindness that changed her life. The chimp had difficulty lactating after birth and lost her babies—when de Waal and his colleagues gave her a baby bottle and allowed her to feed a newborn, she kissed them with gratitude and fed the infant expertly. Kuif was able to save her next baby using the bottle method and became de Waal’s close lifelong friend.

De Waal sees depth in the creatures he’s spent years observing. He’s watched their relationships, the expressions on their faces, their fights and friendships, and come to see that they love, hate, reconcile, relate, play, plan, work, grieve, and rear young a lot like us.

The primatologist sees the individuality and intelligence of the creatures he studies. And he notes that people with pets are often more capable of granting animals their due than scientists because the dog or cat or bird lover simply relates to the animal in their lives and doesn’t have to categorize or quantify or prove anything—they just experience their pets’ depth.

Hiding from ourselves

We have no problem acknowledging that humans are emotional creatures, and that our feelings often stem from knowledge. For example, when a loved one dies, we grieve because we know we won’t see them again—the knowledge informs the sense of sadness. But when it comes to animals, scientists have long been reluctant to attribute depth to emotional expression, relegating everything to primal drives instead.

Yet de Waal has observed the grieving rituals of chimpanzees and he sees little difference between their behavior and ours. The chimps touch, wash, and groom bodies of the dead. They mourn. This indicates then that they have a sense of finality—which implies a sense of the future, some knowledge that this companion won’t be around tomorrow. While chimps don’t bury corpses, de Waal argues that it’s because they roam in the wild and so are not conscious of how the dead attract carrion and scavengers if left in the open to decompose. But de Waal doesn’t put it past the primates to learn and cover or move corpses if they did hang around long enough to discover as much.

He points to experiments on dogs awaiting treats in brain scanners that show activity in the same region of the brain, the caudate nucleus, that lights up when businessmen are promised a monetary bonus as more evidence of our many similarities. In de Waal’s view, the more we know about animals, the more it’s apparent that we are animals and that our minds are not unique. “Instead of treating mental processes as a black box, as previous generations of scientists have done, we are now prying open the box to reveal a shared background,” he writes. “Modern neuroscience makes it impossible to maintain a sharp human-animal dualism.”

Amongst some professionals, there’s still resistance to embracing our animal brethren and acknowledging we’re family. De Waal believes it’s because seeing the full range and depth of animal feelings will expose our own animality to us. He notes that we refer to the human drive for power as “leadership” and don’t discuss the fact that we are a hierarchical species and some of us want to dominate, just like some apes want to climb to the top of ape culture. When de Waal once discussed the human power drive at a psychology conference he was taken aback by the negative response. He writes, “You’d think I had shown them pornography!”

Yet no amount of euphemism use can disguise the truth from de Waal and an increasing number of animal researchers who contend that we are hiding from ourselves when we deny the humanity of animals or the animality of humans, whichever way you prefer to put it. And these scientists are changing the way we understand ourselves and other creatures, shifting the burden of proof on those who refuse to acknowledge similarities to show that there really is a stark divide between the inner lives of animals and our own, rather than vice versa.

Throwing down the gauntlet and declaring a new age, he argues that it’s now time for the anthropodeniers to show there’s reason to believe humanity is unique. But he doesn’t think they’ll succeed. De Waal writes, “Anyone who wants to make the case that a tickled ape, who almost chokes on his hoarse giggles, must be in a different state of mind from a tickled child has his work cut out for him.”