Imagine sitting down to watch a movie and only being able to watch eight minutes of it at a time. That is Hollywood veteran Jeffrey Katzenberg’s vision for the future of TV, although you won’t necessarily be sitting down. The streaming-video platform he is developing, called Quibi (for “quick bites”), is made to be watched on smartphones only, wherever and whenever you find moments during the day. It is slated to launch in April 2020.

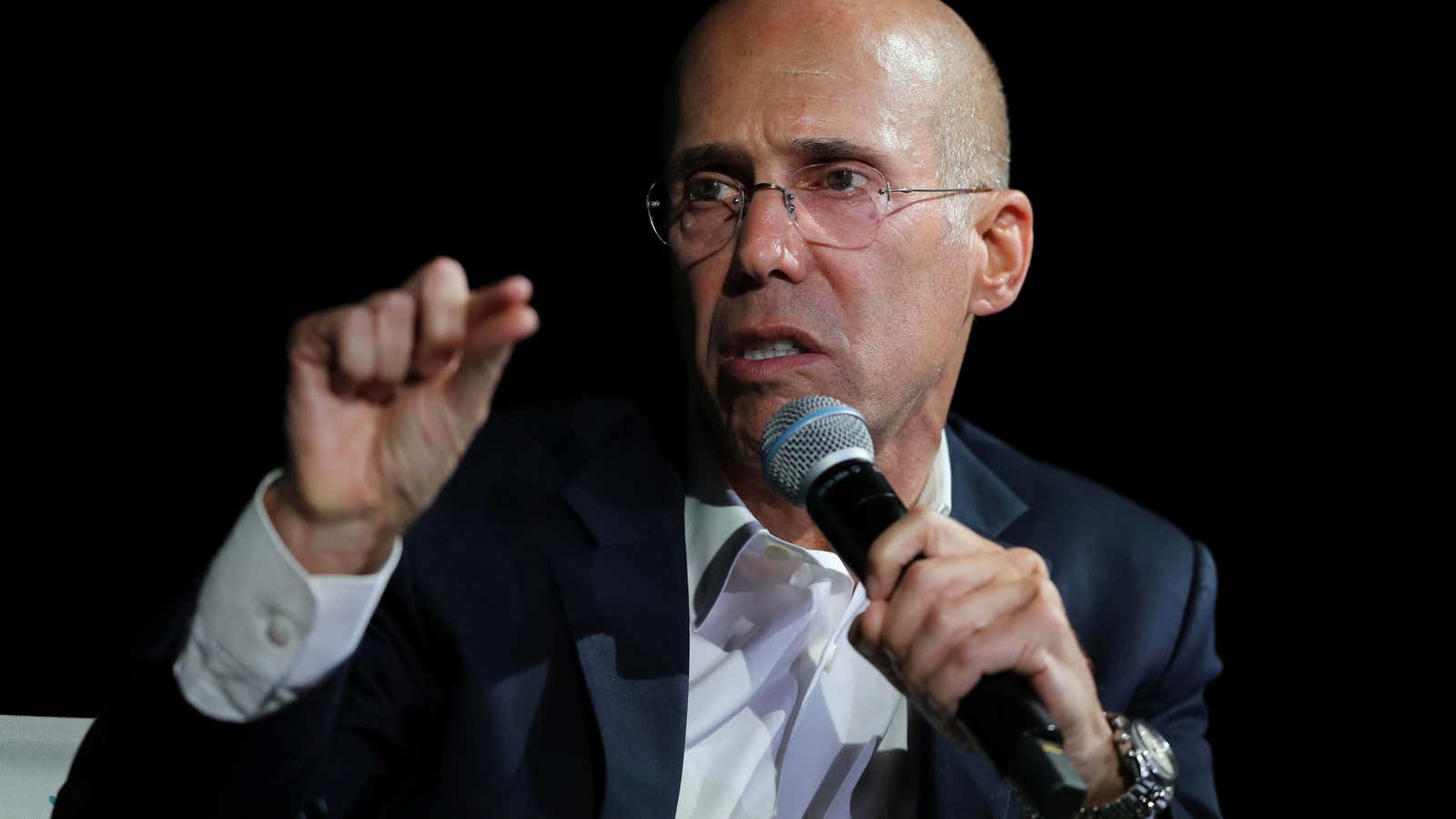

Katzenberg believes that, as people spend more and more time on their smartphones, there’s an audience beyond platforms like YouTube for storytelling from top Hollywood talent that is more easily digestible during people’s busy lives. Many people don’t watch long-form content during the day and very little of it is consumed on a smartphone, the former CEO of DreamWorks Animation and longtime producer told audiences Friday (March 8) at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas.

Quibi is thinking about content for the platform as feature-length films, two hours or longer, that unfold in eight-or-so-minute chapters, which is roughly the length of act breaks between commercials on traditional TV shows like This Is Us.

“What we’re setting out to do falls somewhere between improbable and impossible,” Katzenberg said. “That just happens to be our home address, and we love that.”

Asked by moderator Dylan Byers whether research shows there is an audience for this kind of snackable content, Quibi CEO Meg Whitman, who previously held top roles at eBay and HP, said the company is informed by market research, as well as intuition.

“It’s very hard to research and ask customers about something that doesn’t exist today,” said Whitman. “We’re using a lot of judgment and we’ll know if it works when it launches.”

The platform is currently targeting audiences ages 25-35, in the moments during the day when they might be watching user-generated content on platforms like YouTube, scrolling through social media, or playing mobile games.

Katzenberg likened the way Quibi is trying disrupt short-form video to the rise of HBO during the 1990s. At a time when broadcast TV was still thriving with popular series like Seinfeld and Friends, HBO began releasing expensive original shows like Band of Brothers and Sex and the City that didn’t have commercials and weren’t constrained by TV standards for language, sex, and violence. People were skeptical the model would work.

“They offered a creative challenge and opportunity for storytellers that was unique and differentiated from broadcast TV,” said Katzenberg. “Everything they did to differentiate themselves from TV is what Quibi is doing to differentiate itself from Youtube, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram.”

Quibi’s executives brushed off competition from Netflix and others, which Whitman said would “have to start from standing” developing a library of Quibi-like content, if the model takes off.

“What you can’t do is take an hour-long TV show and chop it up… it has to be written and shot for this use case,” said Whitman. “If we are successful, there will be plenty of competition. We will have accumulated a library [of content] that they can’t go buy.”