A dollar goes a lot further than it used to.

We’re not talking about how much a dollar buys. We’re talking about how long it lasts.

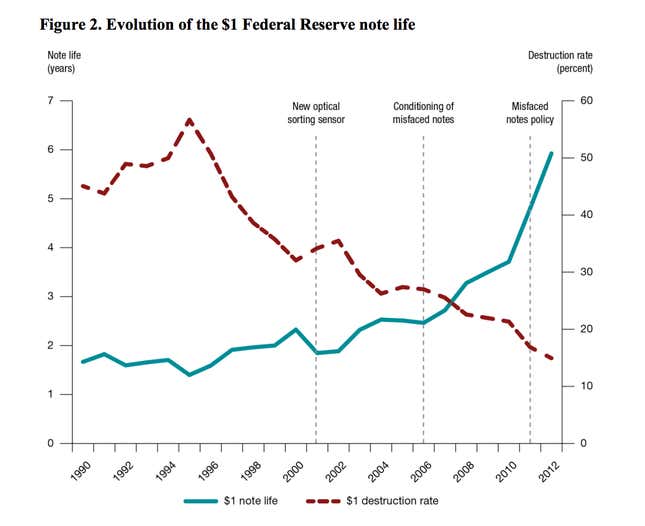

According to a fresh report (pdf) from the US Federal Reserve, the average lifespan of a $1 note was just 18 months back in 1990. By 2012, it had grown to 70 months, or about 289% longer.

Why? Mostly because the Fed, which is the issuing authority of the US currency, is destroying fewer dollars than it used to. Check it out:

The Fed used to destroy a ton of otherwise serviceable dollars for one simple reason: They were upside down (pdf) when run through the central bank’s high speed sorting equipment:

Misfaced notes are notes that are reverse-side up rather than portrait-side up. Before April 2011, for operational reasons, misfaced notes were destroyed during Reserve Bank processing even if they were otherwise fit for recirculation. During 2010 and 2011, the Reserve Banks installed new sensors on their high-speed processing equipment, which enabled them to authenticate notes regardless of facing.

Toss in a couple policy changes, and the average lifespan of a dollar bill has skyrocketed. That’s a good thing. After all, money isn’t free. In 2012, the Fed paid the US Treasury Department’s Bureau of Printing and Engraving, the entity that actually prints the currency, about $688 million to produce around 7.8 billion greenbacks of all denominations.

Correction: A previous version of this post said the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Printing and Engraving produced 7.8 million banknotes for the Fed in 2012. The correct number was 7.8 billion.