Time is money: Duh. But how much money, exactly?

That’s the question to ask if you want to figure out how best to ship your global goods. Increasingly, businesses opt to send their merchandise through the air. Despite the fact that air shipment costs 6.5 times as much as sea freight, about one-third of US imports by value entered the country on a plane and about two-thirds left that way, and those proportions are increasing: Global usage of air cargo grew 2.6 times faster than ocean cargo between 1965 and 2004, according to analysis by economist David Hummels.

You probably know how the cargo container changed the world, acting as a force multiplier for the global shipping industry. But more recent trends have made time more important. One is that, dollar for dollar, traded goods are getting lighter (pdf, p.4). Another is just-in-time manufacturing, where components spread across international supply chains have to arrive at factories when they are needed; if they are late, facilities can stand idle and productivity stops. That’s likely why 41% of trade identified as components is shipped through the air.

Yet another reason is the need to respond to consumer demand. Whether it’s opening day for a new Apple product or a fast-fashion company like Zara catching a fleeting trend, speed is key. Even toy manufacturers get in on the game during the holiday season, waiting as long as they can to see which toys will be best-sellers and then getting more of them into stores. And of course, food and flowers face spoilage.

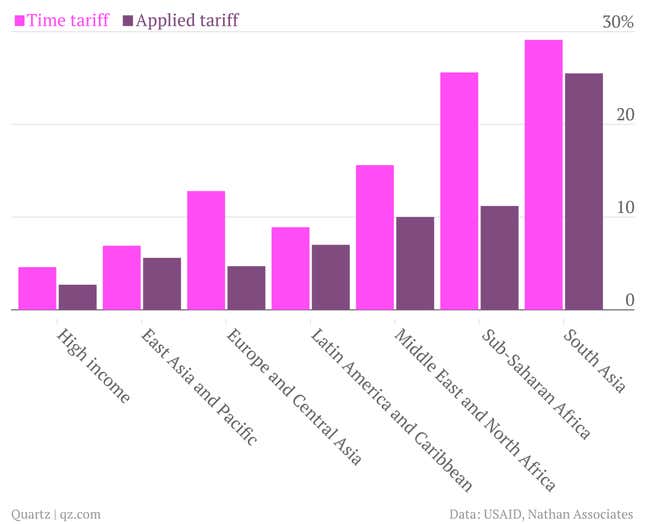

Despite air cargo’s expense, it’s worth it as a way to cut down on transit time. Even in high-income countries, it takes an average of 5.5 days for an imported good to clear customs, exit the port, and head inland to reach customers. In East Asia, it’s 8.7 days. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the slowest place, the average is 28.5 days.

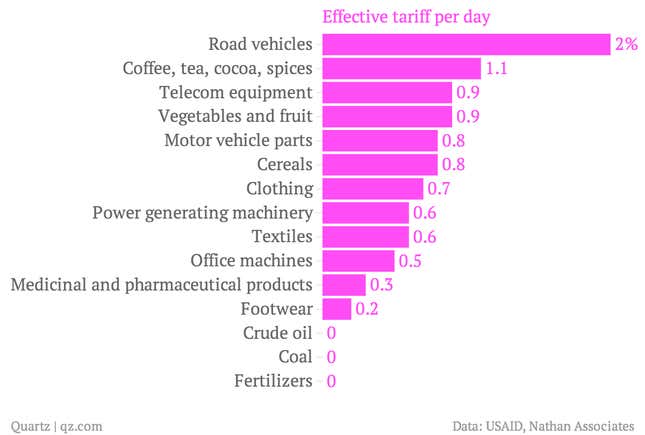

How much does that delay cost? It depends on the good, but Hummels and his colleagues calculated the cost of delays by expressing them in the same terms as import tariffs, i.e., as a tax on the good’s value. Vehicles, with their high storage costs, top the list—each day of waiting is like adding a 2% tariff—while bulk commodities like coal and fertilizer can sit pretty much indefinitely:

But air cargo is pricey, and it also has a far higher carbon footprint, which could make it pricier still if governments ever get around to imposing a cost on carbon. Merchants have looked for better ways to reduce the time costs of trade, which on average outweigh the costs imposed by actual tariffs:

That’s one reason people are bullish about the trade deal concluded by the World Trade Organization in Bali earlier this month. While there wasn’t much movement on tariffs, the deal—the first membership-wide agreement in the WTO’s 18-year history—does target the waiting time that’s arguably a bigger problem. It gets rid of red tape, streamlines customs procedures and gives countries incentives to invest in port facilities.

If the Bali deal works, the time savings could slow air cargo’s expansion. But the overriding importance of reaching consumers and manufacturers on time means air cargo is still likely to keep growing.