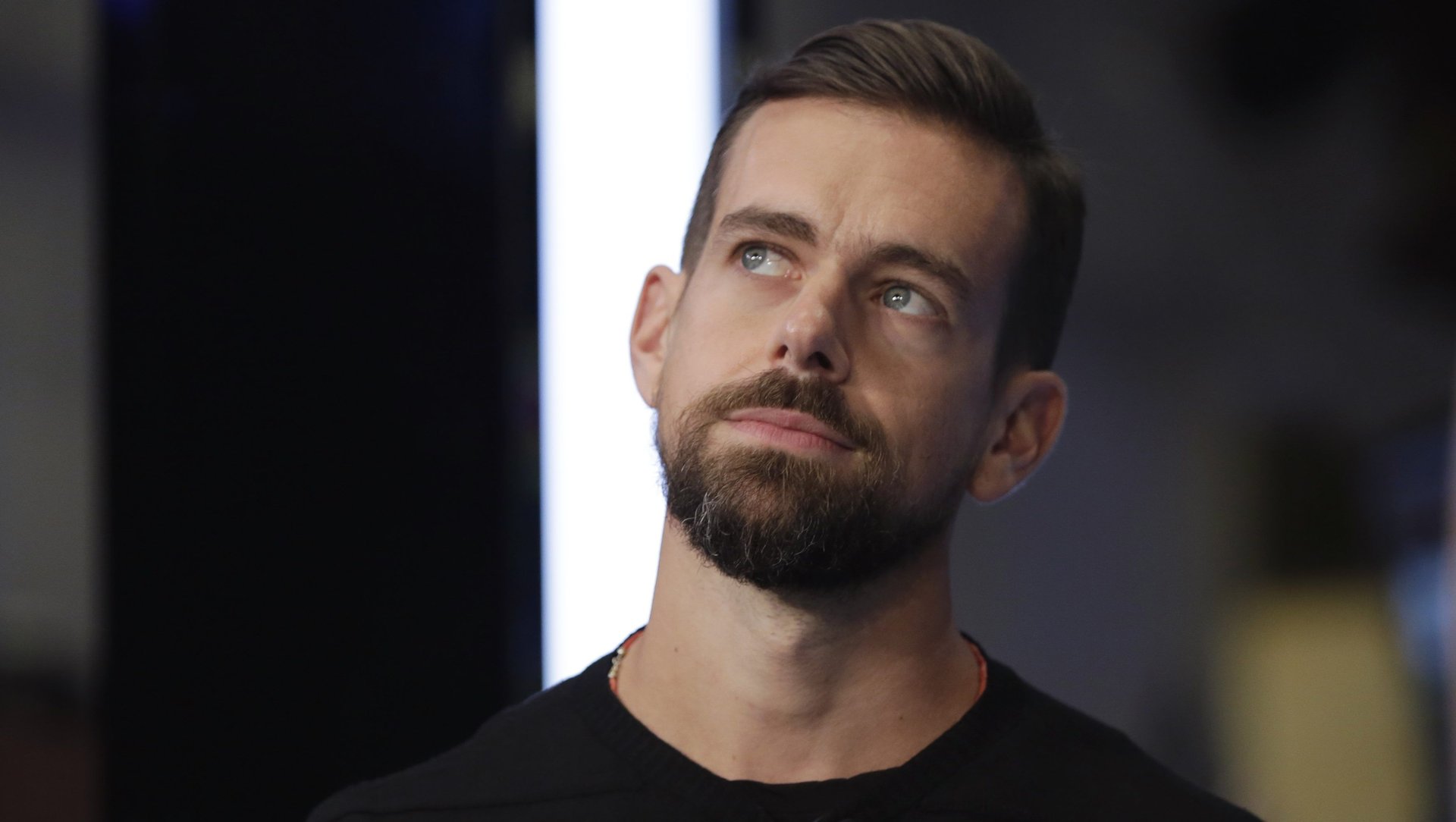

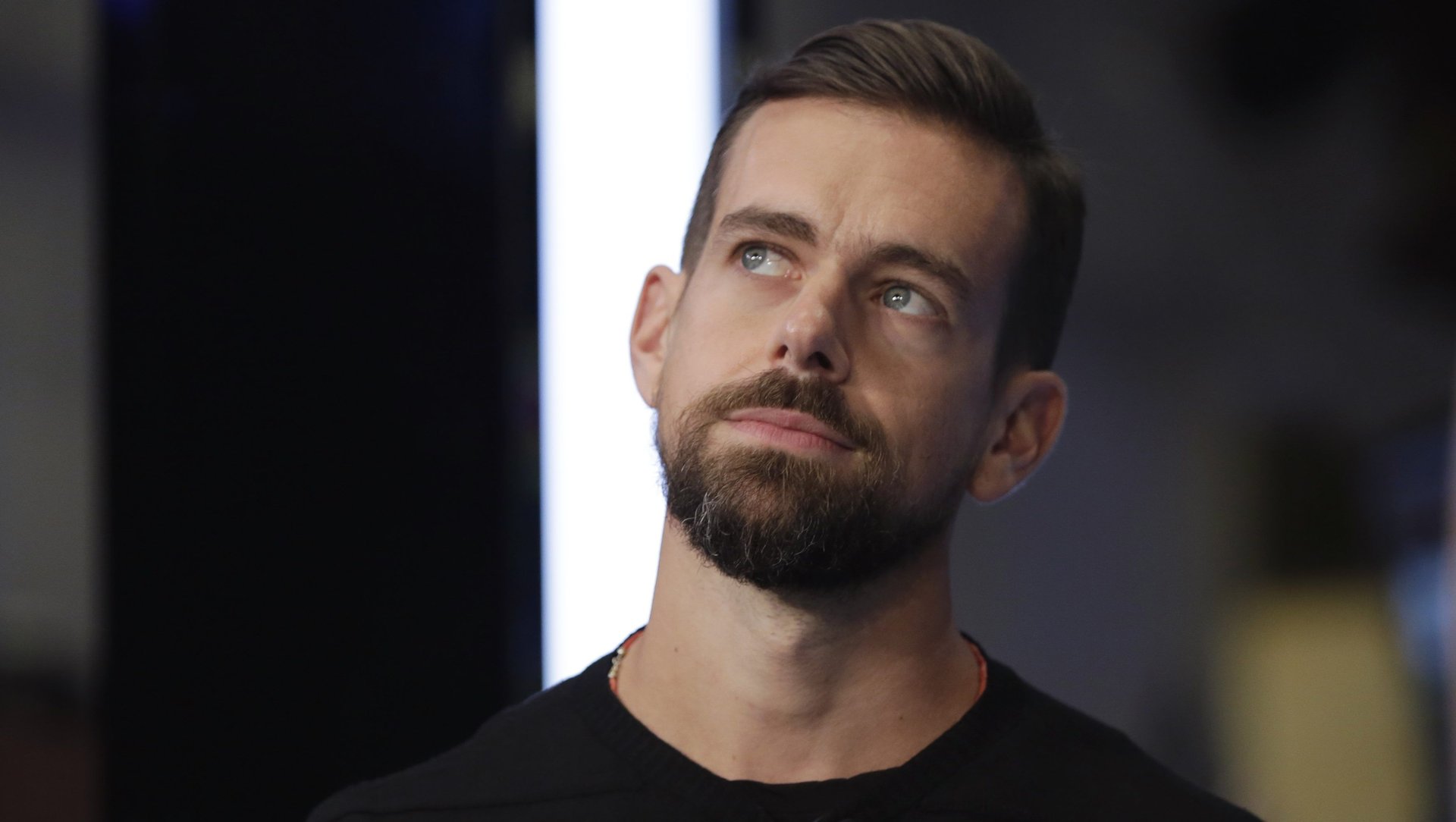

Jack Dorsey doubles down on bitcoin development

Jack Dorsey, the dual CEO of Twitter and Square, announced last week that he will hire a handful of engineers and a designer to contribute to the cryptocurrency ecosystem.

Jack Dorsey, the dual CEO of Twitter and Square, announced last week that he will hire a handful of engineers and a designer to contribute to the cryptocurrency ecosystem.

The new engineers “will focus entirely on what’s best for the crypto community and individual economic empowerment, not on Square’s commercial interests. All resulting work will be open and free,” Dorsey later tweeted.

Square’s support for open-source development was quickly applauded by the crypto community. “Jack gets it,” tweeted Changpeng Zhao, CEO of the Binance exchange. “Thanks Jack, this is awesome,” added bitcoin entrepreneur Matt Odell.

Dorsey’s mini-hiring spree was apparently inspired by a conversation he had with Mike Brock, a Square engineer who helped integrate bitcoin payments into the company’s Cash App, a competitor of Venmo. Brock’s suggestion—to “pay people to make the broader crypto ecosystem better”—was a simple answer to a difficult question. Indeed, how do you advance or modify networks, like bitcoin, that aren’t owned by anybody? It’s like drumming up support for world peace. Nobody’s in charge, but there are hundreds, maybe even thousands, of people whose support could prove influential. To some extent, sponsoring open-source crypto developers is like funding a think tank devoted to ending war—you have to start somewhere.

If you want to alter bitcoin’s speed, storage, or economics, there isn’t a governing body to petition or a CEO to approach. Nobody can force anyone else to adopt a bitcoin update. Instead, a loose community of participants—miners, bitcoin buyers, and developers—coalesces around suggested changes. Cryptography message boards and social media channels play a vital role in organically building support for potential changes to bitcoin’s protocols. Ultimately, a small group of software developers, who have access to bitcoin’s code hosted on GitHub, decides what makes it into production. But if, for some reason, the wider community of users loses faith in these “core developers,” bitcoin can continue without them. That’s part of what makes bitcoin robust and virtually unstoppable, but also slow to change.

In a February interview, Dorsey said he believes “the internet will have a native currency” and of course, bitcoin is the leading candidate for that role. The cryptocurrency has mainstream name recognition and first-mover advantage. Bitcoin’s market cap is $71 billion. Its closest competitors, ether and XRP (Ripple), are each at least $50 billion behind. Furthermore, bitcoin has persisted despite network attacks and vulnerabilities while retaining its price edge over offshoots and alternatives. In its decade of existence, bitcoin has become part of the cultural fabric of being online, first on the dark web and now among the investing public.

Dorsey, though, envisions bitcoin the same way it was billed by its anonymous creator in 2008—as an online currency, not as “digital gold,” the way it’s been treated by some speculators. In fact, last March, Dorsey backed Lightning Labs, a startup that’s trying to make bitcoin payments faster, so that it really can be used as money.

By hiring open-source developers through Square, a publicly-traded company, Dorsey is not-so-subtly blurring the line between corporation and community. Square, which didn’t respond to a request for comment, could benefit from increased bitcoin usage on its Cash App—last year, the company generated $166.5 million in revenue from sales of bitcoin—but how the crypto community responds to the company’s open-source contributions remains to be seen.

Square’s hires are an important reminder that open-source development isn’t really free. Somebody out there is expending time and energy, and they should probably be compensated for it, particularly if their resultant work is a public good. Regardless, as the first major company to explicitly support open-source cryptocurrency development, Square arguably sets a new standard for making financial infrastructure globally accessible. If more companies commit talent to the crypto revolution, then maybe bitcoin will become the online currency that Dorsey imagines.

“I love this technology and community. I’ve found it to be deeply principled, purpose-driven, edgy, and…really weird. Just like the early internet! I’m excited to get to learn more directly.” Dorsey tweeted.

🔑🔑🔑

What you need to know—and why

Central bank digital currencies could threaten the financial system

Digital payments have been readily embraced by retail consumers, who use mobile applications to send and receive money. However, taking that a step further to make money entirely digital could negatively impact the balance between commercial and retail banking, warned Agustin Carstens, general manager at the Bank for International Settlements. Carstens, the former governor of Mexico’s central bank, expressed concerns about central banks potentially becoming lenders and worried that a premium could emerge between central bank deposits and retail bank deposits.

This isn’t a problem particular to digital currency, but one that’s specific to central bank-issued currencies. Cutting out retail banks is potentially destabilizing and digital currency makes a direct relationship between citizens and central banks more feasible, more likely, and more dangerous. Referring to the “huge operational consequences” of central bank money, Carstens also noted that while central banks have studied the possibility of CBDCs, hardly any plan to issue such a currency in the short or medium term.

Takeaway: As Carstens pointed out, “The important part of the acronym CBDC is not the ‘D’ for “digital.” Instead it’s about the first two initials—”CB,” or central bank. A central bank-issued digital currency would not offer a clear advantage over the existing financial system, and may actually undermine or destabilize the retail banking sector, he observed. The impetus for CBDCs seems to have arisen from the crypto community’s belief that inflation is theft, but for society at large, the answer is clear: CBDCs are a rotten idea. ➡️