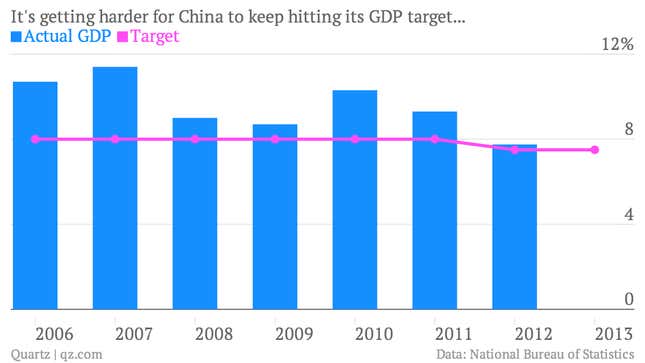

Should China’s economy aim to grow at a 7% clip in 2014? Or 7.5%? That was the biggest dilemma for China’s leaders as they sat down to the big Communist party economic planning pow-wow from Dec. 10-13 to set growth targets. Though the party will announce the target itself in March, the results of the China Economic Work Conference (CEWC), as the meeting is known, hints what that target will be.

That’s important because it telegraphs which priorities will earn provincial party leaders a promotion. A 7.5% screams “borrow, build and do whatever else you can to boost growth.” The lower one says to emphasize that much-discussed structural reform.

It looks like 7.5% is the magic number for 2014. The clues come from the renewed focus in growth evident in the CEWC’s commitment to “proactive fiscal policy and prudent monetary policy.” In non-bureaucrat speak, that means “keep stimulating, everyone—we’ll keep the easy money coming.”

More importantly, though, it signals that China’s leaders are putting those structural reforms on the back burner, even though many think they’re urgently needed for the country to avoid a financial crisis. To hit 7.5% growth, China will need to do the following:

- Generate a lot more investment, most likely in unneeded infrastructure.

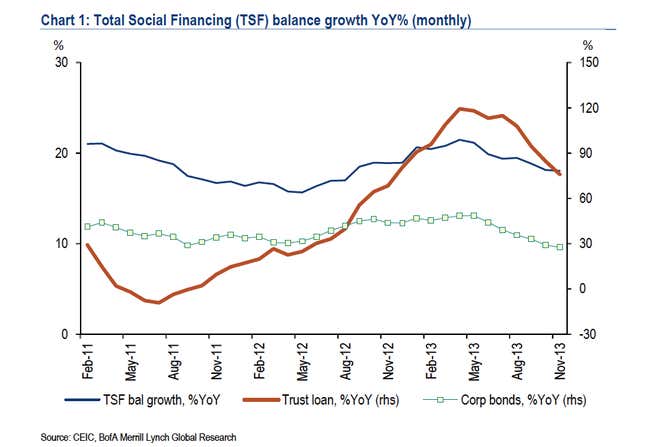

- Keep forcing down interest rates and pumping credit into the system.

- Postpone meaningful restructuring of inefficient state-dominated industrial sectors that produce far more goods than the economy actually needs—industries like shipbuilding, coal and steel.

- Let China’s frothy housing market keep growing.

That’ will make it really hard to reform. Here’s why:

- More state-led investment will only add to already high piles of debt encumbering Chinese businesses.

- Investing in more infrastructure and propping up sectors with overcapacity shifts money toward projects that create minimal economic value money. It also siphons money away from the many non-state businesses that could generate real returns were they not starved for capital.

- Property market reform—particularly a real estate tax and letting farmers own land—is crucial to preventing certain pockets local governments from taking on even more debt and seizing land from households.

Oddly enough the CEWC actually vowed to address a lot of these problems. Building on priorities laid out in the Third Plenum, the party meeting that set the agenda of president Xi Jinping and premier Li Keqiang’s rule, it called for slashing industrial overcapacity, controlling local government debt and promoting “balanced” growth. It also said tax reform for local governments was key to urbanization (or “town-ization,” more accurately).

At least on one topic, the government refrained from speaking out of both sides of its mouth. Last year, the CEWC mentioned “unswervingly maintaining property market controls” for the third time since 2010, as China Real Time flags. This year merited no such mention, even as housing prices, jumped nearly 11% in November (paywall), versus November 2012. But despite the admirable shift away from empty slogans, that’s another sign that growing 7.5% will be more important than reform in 2014.