To read a man’s mind, first you have to outline his skull.

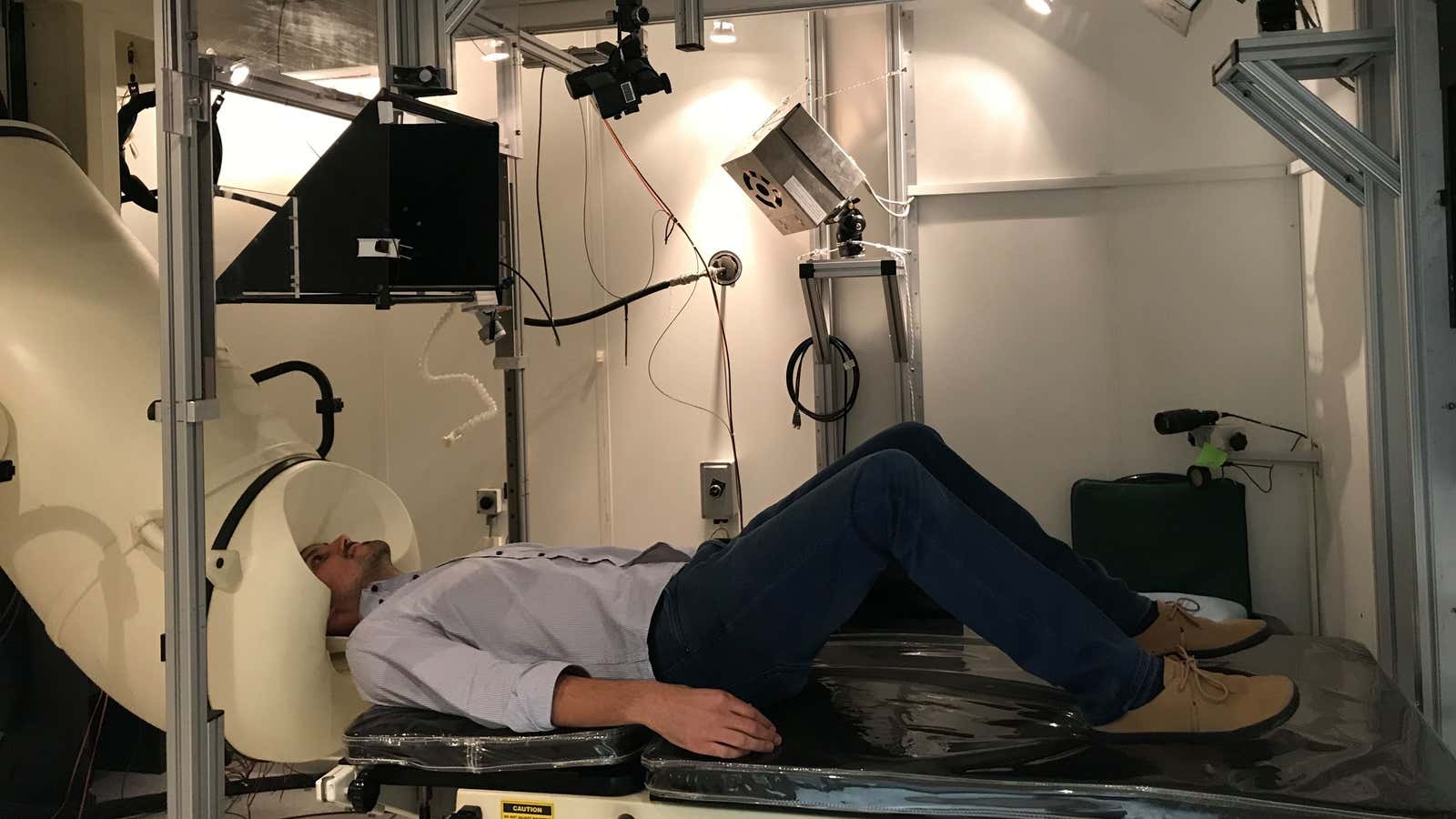

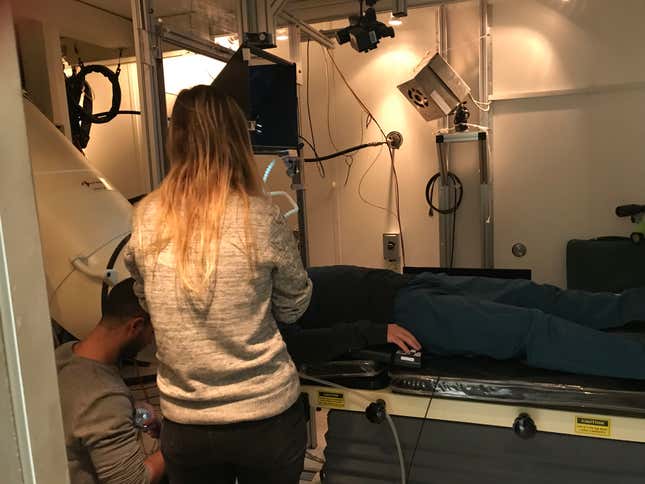

Last November, I watched a psychologist use a digital pen to draw the circumference of a man’s head. The coordinates of his brain were quickly mapped, pinpointing the precise areas within his skull that process emotions. Behind him, a massive magnetic mind-reader—a neuroimaging device called a magnetoencephalography, or MEG—emerged from the wall, funneling into an oversized white helmet. It took two scientists to slowly maneuver the apparatus into position around his head.

As the man lay still, staring blankly up at a screen, researchers crossed wires over his body and taped sensors to his temples. Yoav (a pseudonym, as he asked to remain anonymous), a 28-year-old political science student at Bar Ilan University in Israel, was paid 110 shekels (around $30) for his time, and didn’t know he was about to become part of an experiment attempting to change his mind about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

After Yoav was strapped in, a team of psychology researchers began to challenge his ideas using a technique called “paradoxical thinking.” The premise is simple: Instead of presenting evidence that contradicts someone’s deeply held views, a psychologist agrees with the participant, then takes their views further, stretching their arguments to absurdity. This causes the participant to pause, reconsider, and reframe their own beliefs.

Though interesting in its own right, the experiment is part of a grander mission. It’s one piece of a detailed program, run by social psychologist Eran Halperin at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya University (IDC Herzliya) in Herzliya, north of Tel Aviv, to understand the psychology behind the Israel-Palestine conflict—and to change it. His goal, more than publication in respected journals or academic accolades, is to create the psychological conditions for peace in Israel and Palestine.

🧠 🧠 🧠

“Paradoxical thinking” was first devised in the 1980s to change people’s views about societal gender roles. Two decades later, as part of an effort to change the opinions of societies engaged in conflict, Halperin’s lab showed it also works to shift Israelis’ views about the ongoing confrontation with Palestine. In 2014, Halperin published a paper on the subject in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showing that people exposed to paradoxical thinking developed a more conciliatory attitude about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and were more likely than a control group to vote for dovish parties in the Israeli elections. The effects were still evident one year after the intervention.

The latest version of the experiment, which I saw late in 2018, used a MEG to monitor responses in the brain. The goal is to see if neuroimaging can identify specific brain activity corresponding to emotional responses sparked by paradoxical thinking.

The experiment was run by IDC Herzliya neuroscientist Yoni Levy, with assistance from master’s student Amir Ben-yair and two undergraduates. Ben-yair, who had many practice sessions in preparation for these conversations, conducted the paradoxical-thinking intervention via video, from just outside the MEG room.

“Jewish people are more moral than Arabs. Do you agree?” Ben-yair asked in Hebrew (which he translated for me after). “Yes,” Yoav, lying under the MEG, replied. “And so,” Ben-yair continued, “if you randomly selected one Jewish person and one Arab person, the Jewish person would always be more moral.” “Well, no,” Yoav resisted. “It’s not as straightforward as that.”

Ben-yair ran through his questions in a soft, even voice, halting as he selected the best phrasing. He is skinny, with a gentle, boyish manner, and the ability to create a sense of calm even in tense situations. “Palestinians never really got hurt during the conflict, do you agree?” he asked, beginning a line of questioning that presses on the belief that the Israeli army does not harm innocent non-combatants. “Even if they do get hurt, it’s their fault,” he added

As the experiment continued, Yoav’s responses became terse. Around halfway through, he started laughing. “When I really take it far, participants laugh. It’s a way of coping,” Ben-yair told me afterwards. “It’s really hard to lie there and hear these opinions; it makes you uncomfortable.”

Ben-yair went through his own reevaluation process after he was conscripted into the Israeli army in March 2009. He grew up in a deeply patriotic family and never questioned the value of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) before experiencing it first hand, fighting in the 2012 and 2014 conflicts in Gaza. “The most profound thing I felt when I was there was the absurdity of fighting,” he said. “Suddenly you find yourself in a situation where you might randomly die.” After he left the army, he tried to talk with his friends and family about his new uncertainties, he said, but many were resistant to his new opinions.

There are clear psychological reasons why so many hold fast to their political beliefs, explained Ben-yair. “There are psychological needs that need to be met,” he said. People have a deep-seated desire to believe their opinions are, moral and good. If we want people to change their views, there’s nothing to gain by labelling certain opinions as “stupid” or “evil.” “If we dismiss these needs, and say it’s only a conservative view, we’ll never be able to create anything different than what we have now,” he added.

Working on the paradoxical-thinking experiments has helped Ben-yair understand why some conservative Israelis believe Palestinians are not open to negotiation. That understanding, he said, “gives me the tools to engage and…strength to intervene to create a better, peaceful society. The natural way is for us to [try to] influence only the people we agree with. Why convince liberals who are already convinced?”

In a small room after the experiment, Yoav—the study participant—agreed to tell me about his experiences and views. He doesn’t expect a resolution to the Israeli-Palestine conflict, he said, and would ultimately like the Palestinian population to be integrated with Jordan. During the experiment, he agreed with the statement that the IDF is the most moral army in the world. (Research has shown that members of all societies embroiled in long-term conflict predominantly assert their army is the most moral.) When I pressed him on it, Yoav said the IDF may not be especially moral, but it’s the only army that even tries. “I think the British army tries to be moral,” I ventured, and he shrugged: “Maybe not then.” Yoav said he found the experiment both uncomfortable and intense. “I think you feel very vulnerable and judged,” he added.

I had my own chance to lie on the table and answer questions, and I saw what he meant. I was presented with a series of statements designed to test my own values, such as, “Palestinian terrorists bear responsibility for the conflict.” I had to respond by pressing a button to indicate “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neutral,” disagree,” or “strongly disagree.” It was difficult to choose between these simplistic options. On the one hand, I disagree with using the word “terrorist” to describe those who use violence to fight oppression, and I believe that Israel, as the more powerful military force, bears the brunt of responsibility in the conflict. But, on the other, I question whether those who shoot families at bus stops bear no responsibility for adding to the cycle of fear and insecurity. I felt like a mouse, trapped on a table and under scientific scrutiny. I ended up pressing “neutral,” and regretting it.

🧠 🧠 🧠

Halperin has headed up his lab since 2010, leading more than a dozen postgraduate researchers who conduct experiments on subjects including how exposure to violence affects empathy, how to cultivate hope in a political stalemate, and the role of emotions such as contempt and humiliation in conflict. All are in service of moving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict beyond its decades-long stalemate.

In the lab’s early years, Halperin would take the results of its research to non-profits and NGOs, but he quickly realized it wasn’t having much of an impact. So, in 2015, he founded his own not-for-profit: The Applied Center for the Psychology of Social Change, which draws on psychological theories to create tailor-made interventions to influence political reality for NGOs, schools, and companies. This focus on stepping outside the lab to shape policy and behavior makes Halperin’s already-unusual research program even more remarkable.

It’s rare for psychologists to even create real-world experiments in geopolitical conflicts. Betsy Paluck at Princeton University, who won a MacArthur “genius” grant following her work using radio to promote reconciliation in Rwanda, is one of just a handful conducting such experiments. Separately, few academic psychologists use the results from their research to help shape policy; Stanford University psychology professor Greg Walton, who has done considerable work on the best resources and messages in schools to help children learn is a rare example. Combined, then, Halperin’s focus conducting experiments within a conflict setting, and his work applying the results outside of academia, make his efforts unique.

Halperin’s career began, as nearly all Jewish Israelis’ adult lives begin, in the army. Halperin, born in Tel Aviv in 1975, grew up in a politically left-leaning family, but he and his relatives still believed military service was a worthwhile duty. It was nearly unheard of, he explained, for anyone in his parent’s generation to think otherwise. Halperin was dedicated, and stayed in the IDF for three years longer than the minimal service time of 32 months. While he was serving, a group called “The Mothers,” composed of mothers of Israeli soldiers—including his own—protested Israel’s presence in Lebanon. “I looked at my mother back then and told her, ‘You’re a traitor,’” he said. “This is the kind of brainwashing that each society in conflict does to its citizens.”

In October 1997, during a relatively “normal” period of the ongoing conflict (which meant, at the time, regular but intermittent violence between the IDF and Hezbollah), Halperin—an officer at this point—was leading his troops in Lebanon when they were surprised by Hezbollah fighters. He was shot 10 times, losing a lung and the use of both hands for many years. His right hand has regained much of its function in the time since, though both hands are distorted by tissue fusions and scarring.

During months of frustrating recovery, Halperin decided to study political science and conflict resolution to make sense of the fighting he’d been part of. He studied psychology on the side, he said, in an attempt to better understand his own mind. Half of the soldiers in his squad of 20 died in service from 1996 to 1997, and Halperin spent this time wondering when—not if—he, too, would be killed.

He quickly decided psychology was a crucial missing element to conflict resolution and political science. “I realized that it’s too risky and too costly for leaders to make a move out of goodwill towards peace processes,” he said. Instead, leaders typically only take conciliatory action in response to public outcry, such as that issued by “the Mothers” in the 1990s, which is partly credited with persuading the Israeli military to withdraw from Lebanon.

“I realized that it’s more about bottom-up processes than top-down process,” Halperin said. “I was asking political questions and wanted to create a solution to a political problem, but most of the processes I identified as main engines to this are psychological.”

At the age of 26, Halperin began studying with Tel-Aviv University professor Daniel Bar-Tal, whose research has largely focused on the “psychological infrastructure of conflict.” As Bar-Tal and others in his field have found, nearly every member of a society in conflict believes they are not at fault for the outbreak of fighting, that their army is the most moral, and that they are the ultimate victims of the conflict—regardless of the context. Though the bulk of Bar-Tal’s research has focused on the Israel-Palestine conflict, his ideas have been tested and proven in Cyprus, Northern Ireland, and the Basque country of Spain.

Bar-Tal’s work emphasizes that ongoing warfare is an unusually high-stress circumstance, which leads people to develop certain psychological beliefs as coping mechanisms. Long-term conflicts create a sense of perpetual threat, and there are individual and political needs to establish a sense of normalcy in an extreme situation.

Halperin, like so many in Israel, has successfully managed to make the extraordinary quotidian. When we met, Halperin apologized for being slow in replying to some of my emails ahead of my visit. He was distracted, as Israel had been on the brink of war. “There were missiles all around us and bombing in Gaza. And a week after, it’s like a routine situation,” he said.

🧠 🧠 🧠

In the West Bank, traumatic normalcy reaches its heights.

Halperin hires Palestinian and Israeli researchers for his lab, but both groups face difficulties traveling from Israel to the West Bank. There is, however, one researcher on his team who can easily cross the border.

“Alex” asked to be identified by a pseudonym for fear that those he works with in the Palestinian territories would stop talking with him if they knew he collaborated with Israelis. He’s a German national, and so has the cross-border mobility that most of Halperin’s researchers lack.

One afternoon in November, I met Alex at Mt. Herzl, the southernmost stop on the Jerusalem light-rail line. Together, we then drove over the border.

Driving into the West Bank was easy; there were no security checks to slow us down. The border checkpoints have been erected to prevent bombs and violence entering Israel, and there are no officials in place to inspect those traveling out of Israel and into the West Bank.

We journeyed through the hills; unused train tracks from the Ottoman era were etched in the green valleys below us. Alex was as intent on showing me the physical reality of the West Bank—the “geography of conflict,” as he calls it—as he was on discussing his research. He pointed out the farmed valleys of Battir, which straddle Israel and the West Bank. It’s a UNESCO world heritage site, Alex noted, and the only area along the border that isn’t divided by a wall.

We stopped on a hill called “Everest Lookout,” overlooking both the ultra-Orthodox settlement Beitar Illit and the Palestinian village Husan. There are less than five miles (8 km) between the two, and Alex said people from the two neighborhoods talk with each other and conduct business, despite political hostilities. Israelis sometimes watch sports in the Palestinian town, he added.

After an hour of driving, we parked in Bethlehem, where we walked through cobbled, crowded streets, past street vendors selling fresh pomegranate juice and roasted nuts, to the church where Jesus was allegedly born, 2,000 years ago. “This is also kind of what I want to want to show you…these are normal people, living their lives,” said Alex.

All of this created a different impression of the West Bank than the violence for which it’s known internationally. Though there are sometimes violent protests within the West Bank, Alex said these are scheduled events and so easy to avoid; he feels comfortable enough to live here with his young kids. There are three national parks nearby—a beautiful setting, he said, in which to raise his children.

And yet, even amid the beauty, the sense of perpetual oppression never fades; it’s interwoven with regular life. In Bethlehem, banners featuring the faces of Palestinian activists that locals believe were improperly imprisoned by the Israeli government are hung against railings. One of these is Marwan Barghouti, who helped plan the attacks in the Second Intifada and is now serving a life sentence in Israel for murder. He’s also a popular candidate for political leader.

More than 6,100 Palestinians were in Israeli-run prisons at the end of 2018, according to Amnesty International, some for minor offenses such as throwing stones. Alex said he’s noticed more bullying in school and increased aggression from husbands towards their wives compared to other areas he’s lived, and believes engaging in conflict leads people to express more physical aggression in their personal relationships. Research backs up his anecdotal observations. Violence breeds violence.

The West Bank is defined by how difficult it is to leave the region to travel into Israel—especially for Palestinians. When Alex travels alone through the checkpoints, he gets through easily, he said. But whenever he goes with Palestinians in the car (even those who are dual citizens), they’re met with intense questioning.

Alex was perplexed when I asked him what kind of solution he and those he talks to in the West Bank would like to see. Everyone he knows would like peace and equality, of course. After decades of trying, most people in the southern regions of the West Bank, where he works, just want to be able to make a living and go about their lives without harassment, Alex said, and they don’t care whether there’s a separate Jewish state. They just want the conflict to be over.

🧠 🧠 🧠

Halperin is used to being criticized for his work.

“When I give a presentation in Israel,” he said, “the first question is ‘How dare you do an intervention to change the minds and attitudes of Israelis about the conflict? This is not science, it’s politics!’” When he gives presentations at academic conferences outside Israel, other professors often make comments about how “passionate” he seems.

“In a way, when they say how passionate I am, they’re saying it’s not as professional or as scientific as they’d want it to be,” he said. Scientists are supposed to be objective, and Halperin strives to achieve this by working with Palestinians and Israelis across the political spectrum. Nevertheless, he thinks he would be praised more for the exact same research were it done elsewhere in the world. “The fact that we’re part of the conflict creates a tension,” he admitted. “On the other hand, I do think it’s an important and meaningful experience for me to study conflict as someone who’s part of a conflict.”

Halperin wanted his research team to be half Israeli, half Palestinian. He accepted an equal number of Israeli and Palestinian master’s applicants, he said, but Palestinians who work in Israel have far less job security and economic prospects for future work, and many who completed their master’s did not stay for a PhD.

Siwar Hasan-Aslih, the team’s only current Palestinian PhD student, studies what makes people less likely to engage in advocacy, and how to foment hope among those fighting for Palestinian rights.

She’s had to personally reckon with her decision to collaborate professionally with Israelis. She knows other Palestinian PhD students, she said, who felt their Israeli supervisors suppressed their political freedom of speech, and of one Palestinian researcher whose supervisor pressured her to reflect the Israeli narrative in her work. At Halperin’s lab, however, Hasan-Aslih said, “There’s space for me and there’s room for me to bring the voice of the disadvantaged. I happen to be in a place that I can voice my opinion.”

Though Hasan-Aslih can’t force her lab to not hire settlers (some 500,000 Israelis live in West Bank settlements, which are widely condemned as illegally occupied territories), she can avoid colleagues whose political actions she views as active oppression. As such, she refuses to acknowledge her fellow Phd student, Tziporit Glick, who lives in an Israeli settlement in the West Bank. Halperin said he purposely designed his lab so that everyone has the freedom to choose who they collaborate with.

Glick said she would like to talk with Hasan-Aslih, but respects her decision. Glick lives in Efrat, an Israeli settlement in the West Bank close to Jerusalem and, while she believes in Palestinian rights, does not see the settlement as an affront to those rights. “Where I live was an ancient Jewish settlement known in the Bible,” she said. “So I don’t feel it’s occupied land, I think it’s part of the Jewish land.” She has good relationships with her Palestinian neighbors, she said; she’s often invited to their celebrations, and in turn invites them to Jewish festivities.

“I think [Hasan-Aslih] and I have a lot of common. It sounds weird but I think we do,” she said. Both have suffered from the ongoing fighting; Glick’s brother was killed in the army. They are both young women working on social psychology and studying conflict—Glick is researching the differences between right- and left-wing moral beliefs, and how morality motivates political action. Glick believes dialogue is essential to the peace process. “Although we have very different ideologies about our understanding of the situation in Israel, I think if we could talk about it, it would be helpful to settle some of the social differences between us,” she said.

Talking isn’t good enough, Hasan-Aslih believes. Communication and negotiation were staples of the Oslo process, which was supposed to bring peace, she said, but instead led to more oppression of Palestinians. “I do believe in peace as a value, but I think that this should be based on equality and justice,” she said. “I don’t believe in the peace of the oppressor.”

🧠 🧠 🧠

Halperin aims to be impartial. He doesn’t advocate for any one specific political solution, but instead has three ambitions for the psychological health of Israelis and Palestinians.

One is for Israelis to recognize that Palestinians are a heterogeneous group, and vice versa. Both societies are made up of many groups and a variety of opinions; it’s senseless to ascribe any one viewpoint or action to all Palestinians or Israelis. The second is to create a sense of identity, for both Palestinians and Israelis, independent of the conflict. Finally, Halperin wants to foster a belief in change. Too many Israelis and Palestinians believe the conflict cannot be resolved and, to puncture this pessimism, Halperin’s team has done considerable research on how to create hope.

“If people cannot imagine a future that is different from their current situation, then you cannot even entertain the idea that they’ll do something in order to promote peace,” he said.

Despite his efforts at nonpartisanship, Halperin’s work can be felt as deeply threatening for some of those who live in Israel. Halperin teaches an undergraduate class on psychological barriers in conflicts, where he tells his students that all societies locked in conflict adhere to certain narratives, such as that their armed forces act with more morality than their combatants. In Israel, this narrative is often repeated by politicians and political groups at pains to point out how the IDF seeks to avoid civilian deaths.

The response in the classroom is the same every time, Halperin said: At least one student says, “Yes, this may be a psychological barrier in most conflicts, but here it’s a fact. We are really the most moral army in the world.”

Then, another skeptical student will chime in, asking how supporters of Hamas, the fundamentalist group acting as the de-facto government of the Gaza Strip, could possibly believe their armed forces were acting morally. Halperin answers by sharing his experience of giving lectures internationally, where he always gets the same question—but about Israelis.

🧠 🧠 🧠

Israeli citizens must reckon with the guilt for their country’s transgressions, believes Noa Schori-Eyal, 38, a post-doctoral researcher in Halperin’s lab.

“I keep going back to shame,” she said, as we walked through the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya University campus. “I’m always intrigued by the stories people tell themselves [to avoid these emotions.]” Shame and guilt are necessary to prompt reflection and improvement, and yet these are unpleasant emotions, and many people go to great lengths to avoid them.

Schori-Eyal said she has friends and acquaintances who excuse Israel’s actions. She finds it difficult to talk with them, but tries to do so anyway. “They should not be waived away as incompetent or stupid,” she said. “Their thinking is motivated, but then so is mine and we look at the same set of facts and sometimes we construe them differently.”

Much of Schori-Eyal’s work at Halperin’s lab uses virtual reality to encourage people to, quite literally, see situations from a different perspective. During my visit last November, she was in the middle of an experiment that puts participants into a VR scene where two Palestinians—a pregnant woman and a man—approach an isolated rural checkpoint manned by IDF soldiers. Participants are shown the encounter from either the Israeli soldiers’ or the Palestinians’ perspectives. In the scene, the soldiers are agitated, and the Palestinians feel threatened in turn. The interaction ends with the Palestinian man reaching inside his jacket, saying he’s getting his papers, and the Israeli soldiers reacting with alarm, brandishing their guns.

I watched the VR scene from the Palestinians’ perspective. I put on a headset, and entered an empty field of sun-worn grass and the occasional tree. I was told to look at the ground until the grass started gently blowing in the wind, then to look up. When I did, I found myself walking down a path to the checkpoint, a boulder guarded by two Israeli soldiers. They didn’t see us until we were close; when they did, they reacted with agitation, clutching their weapons. My partner spoke with them in Arabic, tensions rose, and they forced me to open my bag, spill the contents onto the floor, and kneel. At the end of the scene, when I saw my partner reaching into his jacket, the soldiers were yelling.

Schori-Eyal has found that those who experience the scene from the Palestinians’ perspective will, afterwards, express higher levels of empathy towards the Palestinians compared to those who saw the VR from the Israelis’ perspective. They’re also less likely to view Palestinians in general as threatening. This effect has been shown to stick for at least five months after viewing the VR.

When I visited the lab, one participant, a 23-year-old Israeli undergraduate, was, like me, shown the scene from the Palestinians’ perspective. “I don’t think they wanted to attack,” she told me afterwards. I asked her if the scene made her more aware of how scary checkpoints are for Palestinians. She paused, fiddling with her rings. “It’s scary on both sides,” she says, looking down. I’d briefly forgotten that, like all Israelis, she’d spent time in the army. “You don’t know what’s going on,” she said.

Another Israeli participant, a 25-year-old man, saw the scene from the Israelis’ perspective. Omer (who asked to be anonymous and so is referred to by a pseudonym) said he’d seen similar scenes during military training and active duty. He knows there are Israeli soldiers who behave badly, and he knows there’s fear on both sides. “It’s a terrible feeling standing at these places because every day people come and, you know, you’re looking for the 1%, which means 99% of the people I’m going to bother for no reason. And you do it anyway because you have to.”

The military pushes you, he said, into horrendous situations and actions. In a quiet, tense voice, he described being sent into a man’s home in a raid in the middle of the night. “In that case we were right, they had a bunch of weapons in his house under the floorboards, but his mom was there, his kids were there, which is awful.” The man’s mother started yelling, and tried to stop the soldiers. “It’s a woman, an old woman who theoretically won’t do anything wrong,” he told me. But, “anyone can be dangerous. She can be dangerous and you’re just a lot more rough with her than you think you would be.” He breathed out, his voice steeped in shame and defensiveness. “I didn’t punch her in the face or anything,” he said, “but I pushed her away onto the couch.”

Omer said he knows Palestinians are brainwashed. One of the officers in his squad could read Arabic, and so when they arrived in a new Palestinian city they would browse local events on community center websites. One time, they learned of a school play performed by 13-year-old kids, in which they acted as Palestinian adults who go to a border checkpoint. In their enactment, an IDF soldier plants a knife in one of the Palestinian’s bag, and then the soldiers shoot and kill all the Palestinians. “That situation has never happened, but that’s what they’re taught,” said Omer. “So, of course, there’s no reason not to hate us.”

I asked if he thinks Israelis are brainwashed too. “Sure,” he replied, “everyone is, a little bit.”

🧠 🧠 🧠

Many charities and community organizers try to get Israelis to question the view that Palestinians are unwilling to work towards peace by showing them videos of Palestinian leaders saying, in Hebrew, that they are in fact open to negotiatiation.

“This is a classic mistake,” said Halperin. Telling people they’re wrong and presenting the evidence only makes them more defensive. Paradoxical thinking creates far stronger results, and Halperin has shown various nonprofits how to use this approach to encourage people to think differently. But he’s learned from experience that it’s not enough to demonstrate the most effective psychological methods. Which is why, at his Applied Center, Halperin’s researchers work directly with individual schools and companies to create programs based on the insights from their studies.

Yossi Hasson, head of research at the Applied Center and a PhD candidate in psychology at IDC, explains that his team works by diagnosing the problem in each specific environment, training those working there on how to respond, and then implementing an intervention. So far, they’ve worked with 14 schools (which includes 520 teachers and 3,400 students) as part of a pilot for an Israeli government program, Israeli Hope Standard, designed to create collaboration between the four different education tracks in Israel: secular, religious, ultra-Orthodox, and Arab.

In one school, Hasson’s team found that the overall perception of Palestinians was more positive than in the average school, but nevertheless, in a survey, the school’s students reported often hearing their fellow students make derogatory jokes and use other offensive comments about minorities. To address this, the team identified the student in each class who had the highest number of positive connections to others, and asked these social leaders to participate in a weekly “leadership group meeting,” where, for two hours, they’d discuss the current use of and how to eliminate offensive language. Researchers at the Applied Center are now studying the data gathered from this particular intervention, and will have results by the end of the year.

In another Israeli school, the Applied Center found that while students reported less offensive language, they displayed a more homogenous perception of Palestinians. Past studies have shown that seeing all members of a group as sharing the same traits—even if these supposed shared traits are not negative—leads to bias. In addition, previous experiments have found that it’s possible to decrease one group’s homogenous perception of other groups by showing them posters of images of members of other groups featuring individuals of different ages and backgrounds, to demonstrate their diversity. The Applied Center plans to replicate this experiment in this particular school, and to measure the posters’ efficacy in shifting perceptions in this real-world setting.

Halperin was careful to emphasize that psychology is not a quick fix. “There are no magic messages and magic words that will change everything,” he said over coffee on our last day together. Changing the opinion of an entire society takes years. But, by gradually taking research outside of the lab, Halperin believes psychology research can shift the groundswell of opinion. On my final afternoon with Halperin, as I drove with him to a conference titled “Removing Barriers to Middle East Peace,” I asked what he hoped to achieve with his lab. He replied simply: “Peace.”