While in sheer numbers of voters the Indonesian election is no match for India’s ongoing polls, there are still plenty of reasons to consider it one of the world’s most impressive feats of electoral logistics.

Unlike the Indian election, which is staggered over weeks, Indonesia’s will take place on a single day (April 17) at some 800,000 polling stations spread over the Indonesian archipelago of 17,000 islands—about 900 of them permanently inhabited. For comparison, the US had around 117,000 polling places in the 2016 presidential election, with about 224 million eligible voters.

In Indonesia, nearly 200 million people are eligible to vote, and the election commission estimates some 17 million people (paywall), from guards to witnesses, are involved in the process. Six million workers will be involved in running the polling stations. The exercise requires 1.6 million bottles of halal-certified indelible ink for voters to dip their fingers into to prevent double-voting. It’s quite an achievement in a country that has a long history of military dictatorship, and has built its democracy only since the 1998 fall of the strongman president Suharto.

Polls open at 7am local time, and close at 1pm. The country has three different time zones so voters in the west of the country will still be voting after polls in the east have closed. The day will be a public holiday to encourage turnout.

President Joko Widodo is making a bid for a second five-year term, again facing Prabowo Subianto—a former army general he defeated in the 2014 elections. Jokowi, as he’s widely known, is leading in polls and has a fairly good economic track record. But voters are also interested in the religious credentials of both men, as conservatism around faith deepens in a country where nearly 90% of the 264 million people are Muslim. If neither man gets 50% of the vote, there will be a second round of voting.

Indonesians are also voting for national lawmakers and candidates for local assemblies. About 250,000 candidates are vying for more than 20,000 positions.

In a bid to strengthen his appeal to conservative religious voters, Jokowi chose cleric Maruf Amin (pdf) as his vice-presidential running mate. Maruf is head of the governing board of Indonesia’s largest mass Muslim organization. Events leading up to the 2017 Jakarta governor election underscored the importance of paying heed to conservative sentiments. An outcry by hardliners over remarks the incumbent candidate—an Indonesian Chinese Christian, Basuki Purnama—made about Islam while campaigning lost him the election and ended with him tried and convicted for blasphemy. Maruf was among those who called for prosecution of Basuki, who was appointed governor by Jokowi when he had to vacate the post after being elected president.

The coalition of parties supporting Jokowi and Maruf got roughly 60% of the vote in the last election.

Prabowo, the son-in-law of former Indonesian dictator Suharto, chose Sandiaga Uno, a well-known entrepreneur and deputy governor of Jakarta (and one of Indonesia’s 50 richest people), as his running mate. He’s expected to have strong appeal among young voters, who make up a large chunk of the electorate—Australia’s Lowy Institute think tank notes that some 40% of voters are between the age 17 and 35 (the voting age is 17).

Official election results are expected in late April but an unofficial “quick count” process will give an idea fairly quickly of what the result is. The winner will be inaugurated in October.

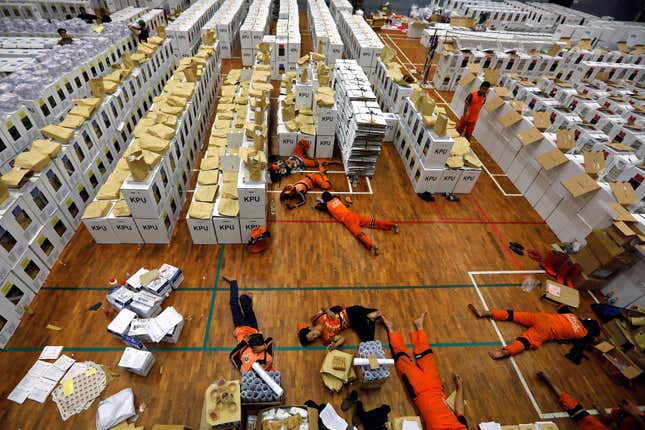

Here are some images of Indonesia’s marvel of a democratic process: