A future AI park in Malaysia shows how criticism is changing China’s foreign investment

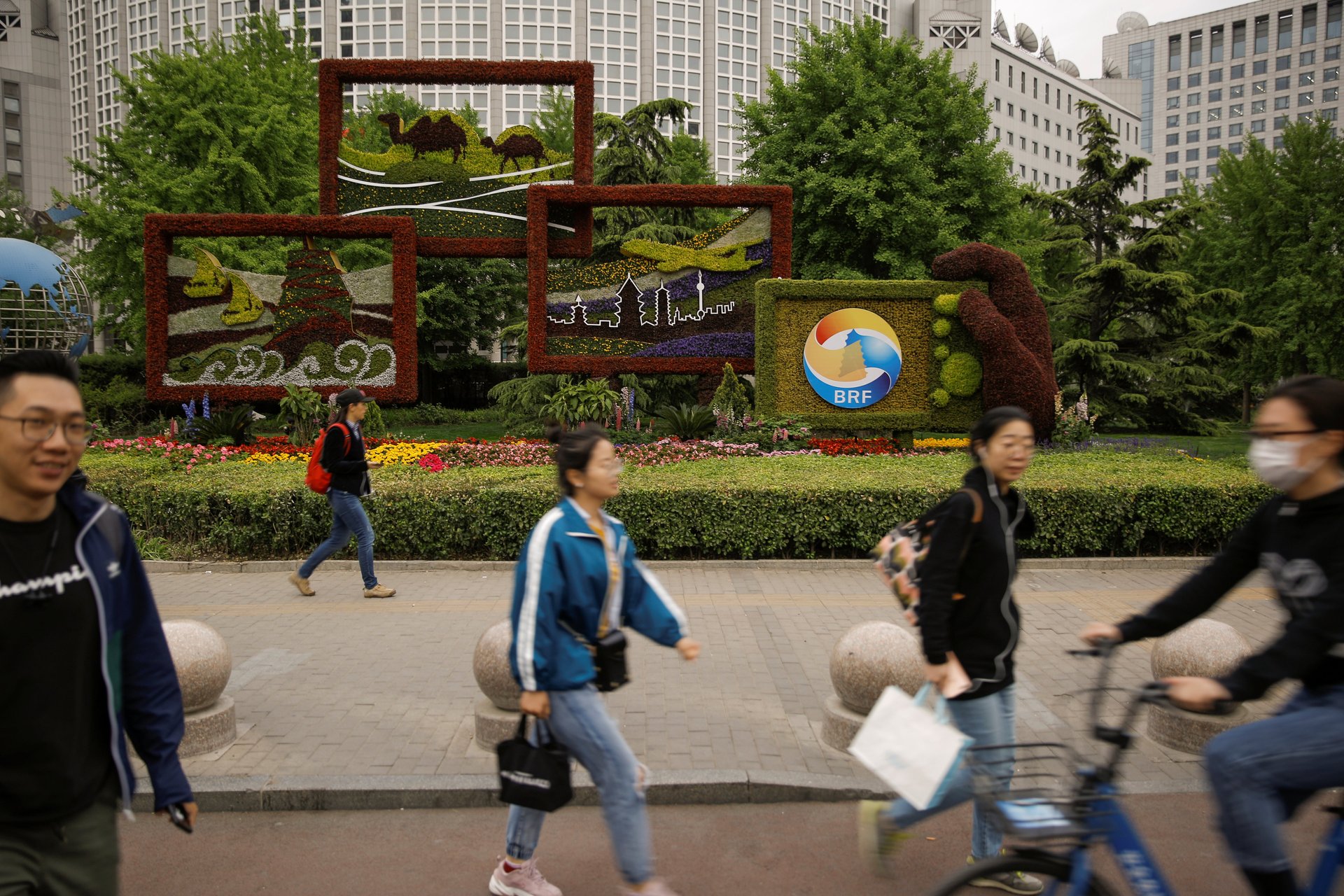

Malaysia was one of the most prominent skeptics of China’s Belt-and-Road investments last year. On Thursday (April 25), prime minister Mahathir Mohamad will be among the more than 30 leaders at the global infrastructure investment program’s second summit in Beijing, a canny symbol of how the controversial initiative is adapting to criticism.

Malaysia was one of the most prominent skeptics of China’s Belt-and-Road investments last year. On Thursday (April 25), prime minister Mahathir Mohamad will be among the more than 30 leaders at the global infrastructure investment program’s second summit in Beijing, a canny symbol of how the controversial initiative is adapting to criticism.

Soon after he replaced former prime minister Najib Razak, Mahathir had suspended some $20 billion in China-backed projects—much of that towards a railway linking ports on Malaysia’s east and west coasts. For a while, it seemed they would be canceled. Then this month, he approved a slimmed-down version of the East Coast Railway Link, and also welcomed a project to create an artificial-intelligence hub in Malaysia with the help of Chinese AI unicorn SenseTime. The $1 billion park, which is supposed to help local tech businesses develop robots and speech recognition, and foster tech talent, will be built by an engineering contractor whose parent is building the railway.

High-tech investment often doesn’t involve large sums or major loans, unlike many past projects of president Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy plan. The AI park is a hybrid, notes Ngeow Chow Bing, deputy director at the University of Malaya’s Institute of China Studies, adding that the deal with SenseTime, in which China offers a “package” of technology transfer and infrastructure construction, might indicate a new BRI strategy.

“The Chinese advances in technologies such as AI, big data and robotics, are the things that the Malaysian government has always been interested in. And [it] hopes China will commit more of this kind of investment,” said Ngeow.

Less “debt-trap diplomacy,” more “digital silk road”

In the wake of fears spurred by Sri Lanka ceding control of a massive port (paywall) to a state-run Chinese port firm, Beijing has been seeking to reassure the world that its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a good thing for emerging markets. It got a chance to do that at a forum for African leaders last September, after months of warnings issued by officials, particularly from the Trump administration, about Chinese debt. In recent months, China has also begun working on better defining what should be considered a Belt-and-Road project, and rules for governing these projects.

The plan got a boost in March when Italy formally signed on to the BRI, becoming the first G7 country to do so.

The focus on technology, which Xi brought up at the previous summit in 2017, is a way to offer something China wants to be known for, and that other countries want, without the visibility of a large or wasteful project.

“We should pursue innovation-driven development and intensify cooperation in frontier areas such as digital economy, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology and quantum computing, and advance the development of big data, cloud computing and smart cities so as to turn them into a digital silk road of the 21st century,” Chinese President Xi Jingping said at a speech at Beijing’s first Belt and Road Forum in 2017.

As part of the so-called digital silk road, China’s also offering to help provide internet connectivity and satellite launches to other countries, as it begins developing a nascent commercial space industry, in addition to artificial intelligence know-how.

The AI park, which will be built over five years, will see China’s SenseTime partner with G3 Global, a Malaysian manufacturer of jeans that is now developing an artificial-intelligence business, the two firms said in a statement. China Harbor Engineering, a subsidiary of China Communications Construction, which is building the railway, will construct it.

SenseTime will provide technology expertise and technical support to G3, while also working with it to develop educational materials for schools in the country. “It is essential for AI courses to be offered in Malaysia as this will be one of the skills required by the future workforce,” the joint statement said. In return, G3 will manage and promote SenseTime’s products within Malaysia.

The two companies will also develop technology for national security, surveillance, immigration, and border security. SenseTime, valued at more than $4.5 billion, is well-known for its cooperation with Chinese police on facial-recognition surveillance. It declined to elaborate beyond the statement on the Malaysian partnership.

Another Chinese AI unicorn, Shanghai-based Yitu Technology, has partnered with Auxiliary Force—a member of the Royal Malaysia Police—to provide body cameras embedded with facial-recognition technology a year ago. It is also working with a Malaysian partner, Build Technology Converge, to deploy the camera system, Yitu said.

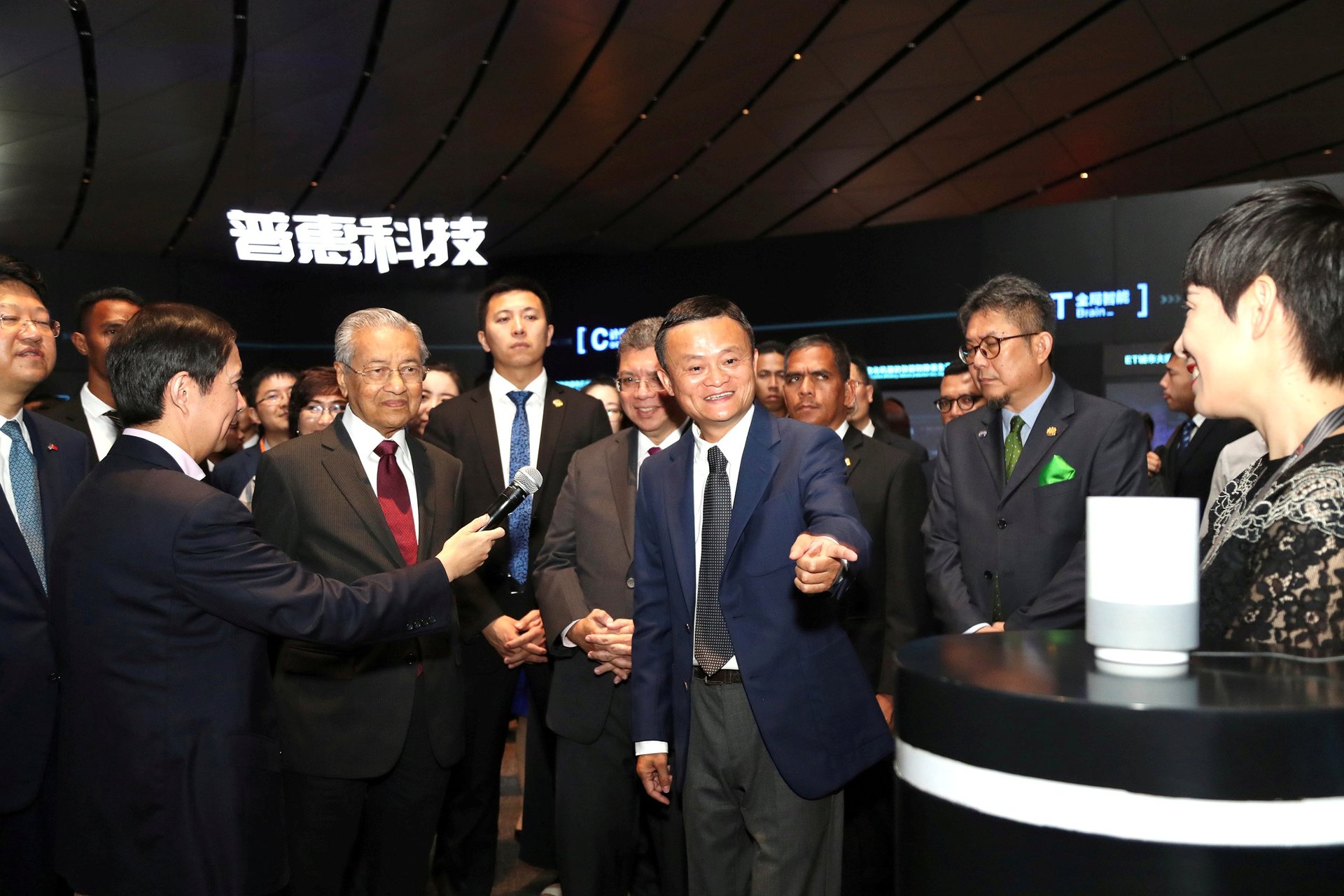

Last June, Alibaba founder Jack Ma, something of an informal ambassador for China’s economic rise, visited Malaysia to open a regional office amid what seemed to be a new prickliness between the two countries, and received a warm welcome. “[W]e will support and empower as many small businesses and young people as possible to use technology to become local kings and benefit from globalization,” said Ma at the time. “This is the beginning of our story in Malaysia.”

Skepticism remains

In recent days China has pointed to Malaysia as a sign that it’s flexible, and willing to adapt its investments to its partners’ concerns. In an editorial in the New Straits Times ahead of the Beijing gathering, China’s ambassador to Malaysia said the East Coast Rail “was rebooted.”

He also pointed to a partnership with China’s Geely automobile firm, which was planned under Najib but finalized under Mahathir, that has helped Malaysia’s homegrown car manufacturer, Proton, roll out its first SUV.

“The Malaysian government is committed to achieving economic transformation, propelling the Industry 4.0 revolution,” wrote Bai Tian in the New Straits Times. “Abundant funds, advanced technology and experiences from China could just be the wind that Malaysia needs during its sailing.”

Some observers say Malaysia shouldn’t become too reliant on any one supplier or lender in technology—and that the AI park may at its heart be basically another construction project.

“This idea that there needs to be an industrial park dedicated to this seems like a very Belt-and-Road idea because it necessarily then involves a lot of construction,” said Jonathan Hillman, director of the Reconnecting Asia Project at the Center for Strategic & International Studies think tank in Washington. “Chinese state-owned enterprises benefit from building those buildings. And it might increase the total amount that Malaysia is borrowing.”