Direct-to-consumer genetic tests like Ancestry and 23andMe were mostly the result of innocent curiosity.

Geneticists at the turn of the century were hopeful that after the near completion of the Human Genome Project, they would be able to provide comprehensive personalized insights to everyone. While this idea may be true eventually, right now it’s still a pipe dream: Individual genetics have so many variations (membership), scientists couldn’t possibly understand them all in the few decades modern genetics has existed.

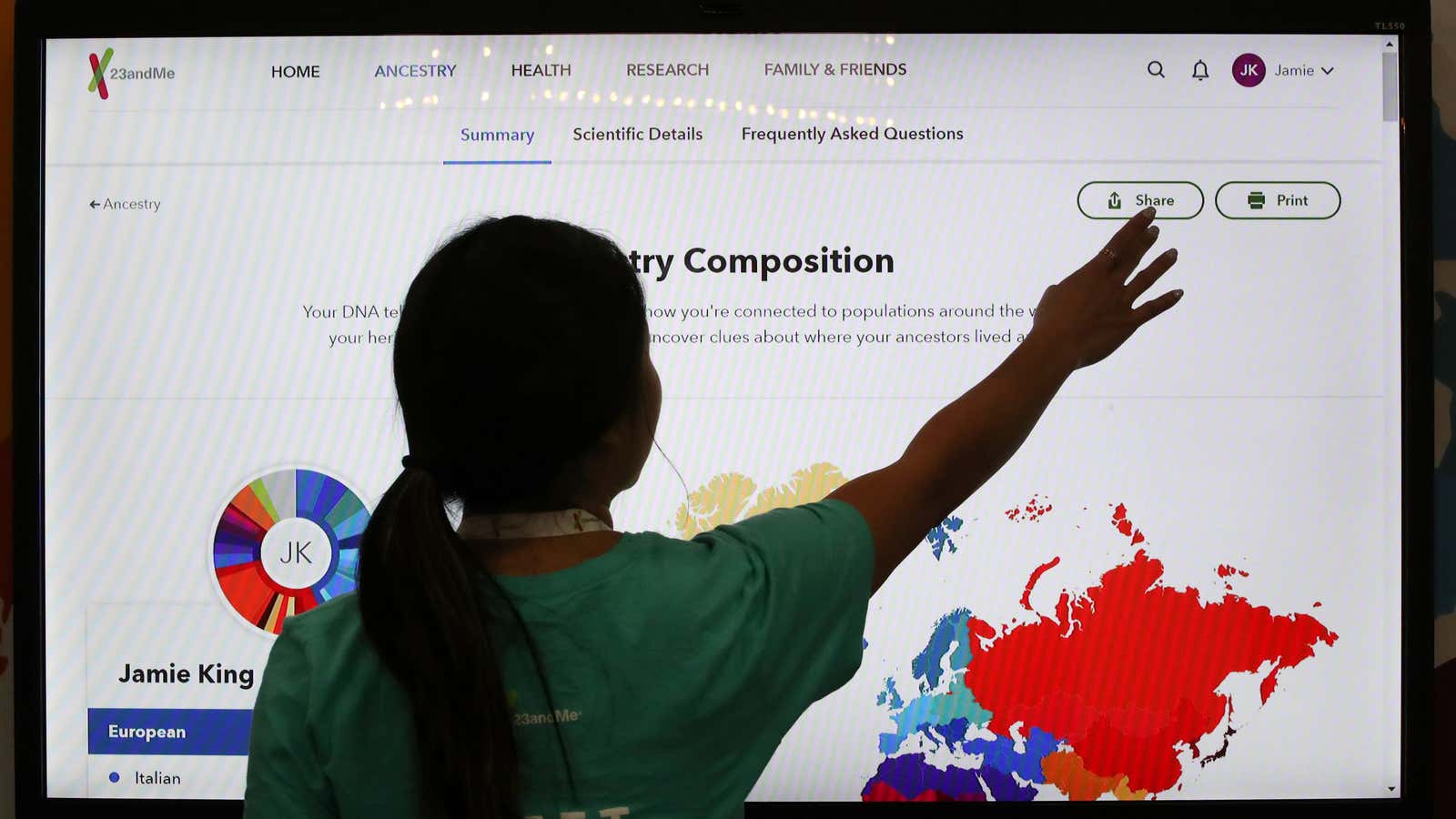

At-home genetic testing companies, though, immediately capitalized on the few variations scientists do understand: a handful related to health and wellness traits, and a few others associated with populations from across the world. The services filled a need (membership). Customers desperately want to understand their genetic material, and now they could, it seemed, with easy-to-read maps and donut charts.

But the designs of these popular tests raise ethical questions. On the one hand, simplified genetic reports make personalized science accessible. They’re also easily shared on social media, adding an element of entertainment. On the other, they obfuscate the nuances and complexities of a growing scientific discipline. Although most companies make their tests’ shortcomings clear in the fine print, users don’t have much incentive to read about them when sleek presentations fool them into thinking they have the full story.

In most cases, these companies risk spreading faulty science communication—a disservice, but not a tragedy. But if they lead customers to misinterpret information about their health, or propagate ideas that ancestral identity can be determined entirely through genetic estimates, the consequences could be disastrous. White nationalists, for example, have used ancestry tests to try to prove their “purity” (membership). And while there’s no data yet to suggest that customers are using genetic test results to justify forgoing medically necessary screenings, it’s easy to see how this could happen.

The growth of these services has been exponential in recent years: Globally over 26 million people have taken some kind of consumer genetic test, and in just five years, forecasts suggest, the industry will be worth $2.5 billion. It’s clear that the services’ popularity won’t go away anytime soon. The long-term effects they’ll have on consumers depend on how their creators choose to clarify the uncertainties of science.

This essay first appeared in the weekend edition of the Quartz Daily Brief newsletter and draws from guides to gene reading recently produced for Quartz members.