Elizabeth Warren’s political awakening came as she pored over long lists of American losers—people who declared personal bankruptcy.

Like any good wonk, her passion was data driven. She was a law professor in Texas, with a conservative bent. When she told me this story in 2009, she was serving as a member of a non-partisan board overseeing the bank bailouts, and declined to specify her political preferences as anything other than “cranky Okie.”

In the 1980s, she and a colleague teamed up with a sociologist to examine the realities of personal bankruptcy. “I undertook the first empirical study to show how families were cheating the system. I thought, ‘I’m going to do the study and uncover abuse,'” she said. “When we got through with the study, and I got a good hard look at the actual facts of bankruptcy, my outlook was never the same. In fact, my personal life was never the same.”

The line of inquiry took her to Harvard Law School, and after the financial crisis, into public service and now a presidential campaign. One turning point on that road brought her directly into conflict with a key rival for the White House, then-senator Joe Biden.

Who loses in a bankruptcy?

In the 1990s, the increasing number of US consumer bankruptcies led to a push by the financial sector to make it harder for people to seek relief from the courts. Lenders argued that deadbeats who had been borrowing to fund lavish lifestyles would then use bankruptcies to erase their debt. It was called the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA).

Warren, a nationally recognized expert on the topic, used her research to argue that the real problem could be found in lax lending practices, like credit-card companies opening accounts for teenagers with no incomes, or the impact of sudden, enormous medical bills on family finance.

Nonetheless, the legislation was enacted, but president Bill Clinton refused to sign it, in part thanks to Warren’s lobbying of first lady Hillary Clinton. With George W. Bush in the White House following the 2000 election, the legislation was reintroduced, and eventually became law. Its top champion among Senate Democrats was Biden of Delaware, a state called home by several major lenders whose employees contributed generously to his campaigns.

BAPCPA proponents note that bankruptcies have fallen since it became law in 2005. But researchers say its main effect has been that financially strapped consumers simply delay filing for bankruptcy, piling up more debts they can’t afford.

Face-off in the Senate

One of the decisive moments came in a February 2005 hearing, when Warren testified before the committee on which Biden sat as the senior Democrat. The collapse of Enron was fresh economic trauma. Warren criticized an aspect of the bill that allowed the Houston-based energy company to conduct its bankruptcy proceedings in Delaware, a jurisdiction where its employees found it difficult to challenge decisions that included the future of their pension fund.

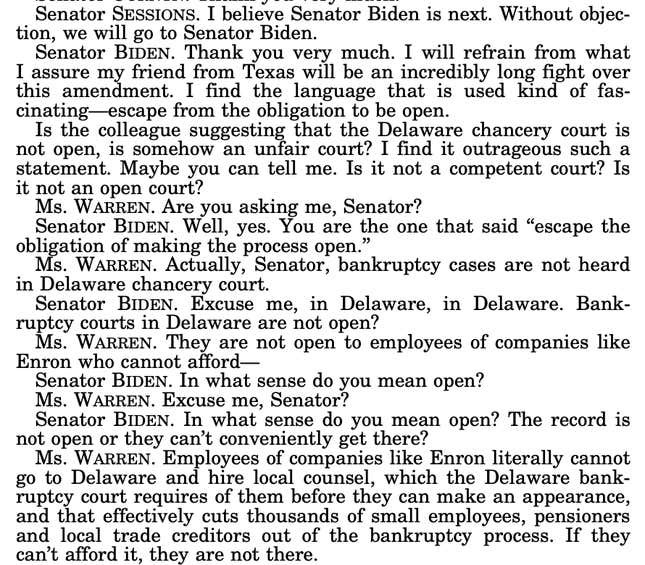

Delaware’s economy is founded on cozy relationships of its courts with corporations, and Biden took umbrage in a series of testy questions for Warren:

Biden then launched into a critique of Warren’s views, suggesting that she was thrusting the responsibilities of the government on innocent businesses. (No, really. It starts on page 30 (pdf).)

“We are going to ask the gas company, the drug store, the automobile dealer to pay for the broken system instead of having the nerve to come and say it is a moral obligation of a nation to pay for that broken system,” Biden complained.

“Until we fix the broken healthcare finance system, those families have to turn somewhere and that means now they turn as a last-ditch effort to the bankruptcy courts,” Warren replied.

Then Biden suggested that Warren’s real complaint was the usurious rates charged by credit-card companies, not bankruptcy law itself.

“But, senator, if you are not going to fix that problem, you can’t take away the last shred of protection from these families,” Warren protested.

“I got it, OK,” Biden replied. “You are very good, professor.”

A 2020 rematch

Warren has said that the experience of seeing the bankruptcy bill pass was a wakeup call. Being right was not enough; the political power of entrenched interests made traditional remedies for consumers obsolete. Two years later, she would publish an article calling for the creation of a federal Consumer Financial Protection Agency as a new, direct solution for the problem of unsafe financial products.

She would also lose patience with members of her own Democratic party who made compromises with the financial sector. When she found herself an adviser in the Obama White House, with Biden as vice president, she clashed with treasury secretary Tim Geithner over the powers that should be given to the new agency when it was created by the Dodd-Frank financial reform law. Ultimately, Obama gave the job of running the new agency to Ohio attorney general Richard Cordray, and Warren ran for a Massachusetts senate seat in 2012.

Warren was one of the first candidates to throw her hat in the 2020 Democratic presidential ring, running on a platform of policy ideas that can be traced to the views of the American economy she developed in her research into bankruptcy. When Biden, a frontrunner in the polls, finally got in the race last week, Warren didn’t waste any words.

“Our disagreement is a matter of public record,” she said. “When the biggest financial institutions in this country were trying to put the squeeze on millions of hardworking families who were in bankruptcy because of medical problems, job losses, divorce and death in the family, there was nobody to stand up for them. I got in that fight because they just didn’t have anyone, and Joe Biden was on the side of credit-card companies.”

In the 2016 primaries, Hillary Clinton’s support for the same bankruptcy law proved a potent critique for Bernie Sanders, who’s also in the Democratic race this time around. On a future debate stage, Biden will have a difficult time changing the subject when Warren lays into him about his links to the financial industry.

His campaign did not respond to Quartz questions about his 2005 vote. Still, it is, as Warren insists, a matter of public record.