“Selling Rune Scimmy 15K.”

I punched away at my keyboard, hoping somebody would bite. I’d just acquired the scimitar sword for 13,000 gold pieces. Instantly, I was ready to sell—and seeking a profit. I tried again.

The letters danced across the screen. But as my character paced outside the bank, my sales pitch was lost in the crowd. Hundreds of players in an assortment of outfits also announced what they were trading: shields, feathers, gold bars, swordfish. Others wanted maple logs, magical stones, and party hats. My voice was one in the chorus of commerce.

Around 2004, when I was 10 years old, I, like millions of others, had my first online experience with RuneScape. With 3D graphics and an extensive map, the game was advanced for the early 2000s. The medieval fantasy world was (and is) a MMORPG, or a massively multiplayer online role-playing game. It’s full of quests to complete, monsters to kill, and best of all, other players to befriend.

In generations past, children entertained themselves exclusively through real-world play. Kids—especially boys—would read comic books, shoot marbles, and trade sports cards. Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, arcades offered a step into digital life, usually outside the home. But the rise of personal computing in the 1990s and 2000s provided a new and more intimate diversion: online gaming. My generation lived at the dawn of this change.

Young millennials, children of the aughts, were the first to spend their formative years on the internet, and our experiences in online games prepared us for the hyperconnected world we inhabit now. Millions played games like RuneScape, World of Warcraft, and other MMORPGs, many of which remain popular. Today, many of our interactions on social media and in mobile gaming are colored by their legacy.

Through MMORPGs, a generation of gamers explored the opportunities—and dangers—of a life spent mostly online. These experiences, had within the relatively safe space of a less sophisticated internet, foreshadowed the types of online decisions people must make today.

The game

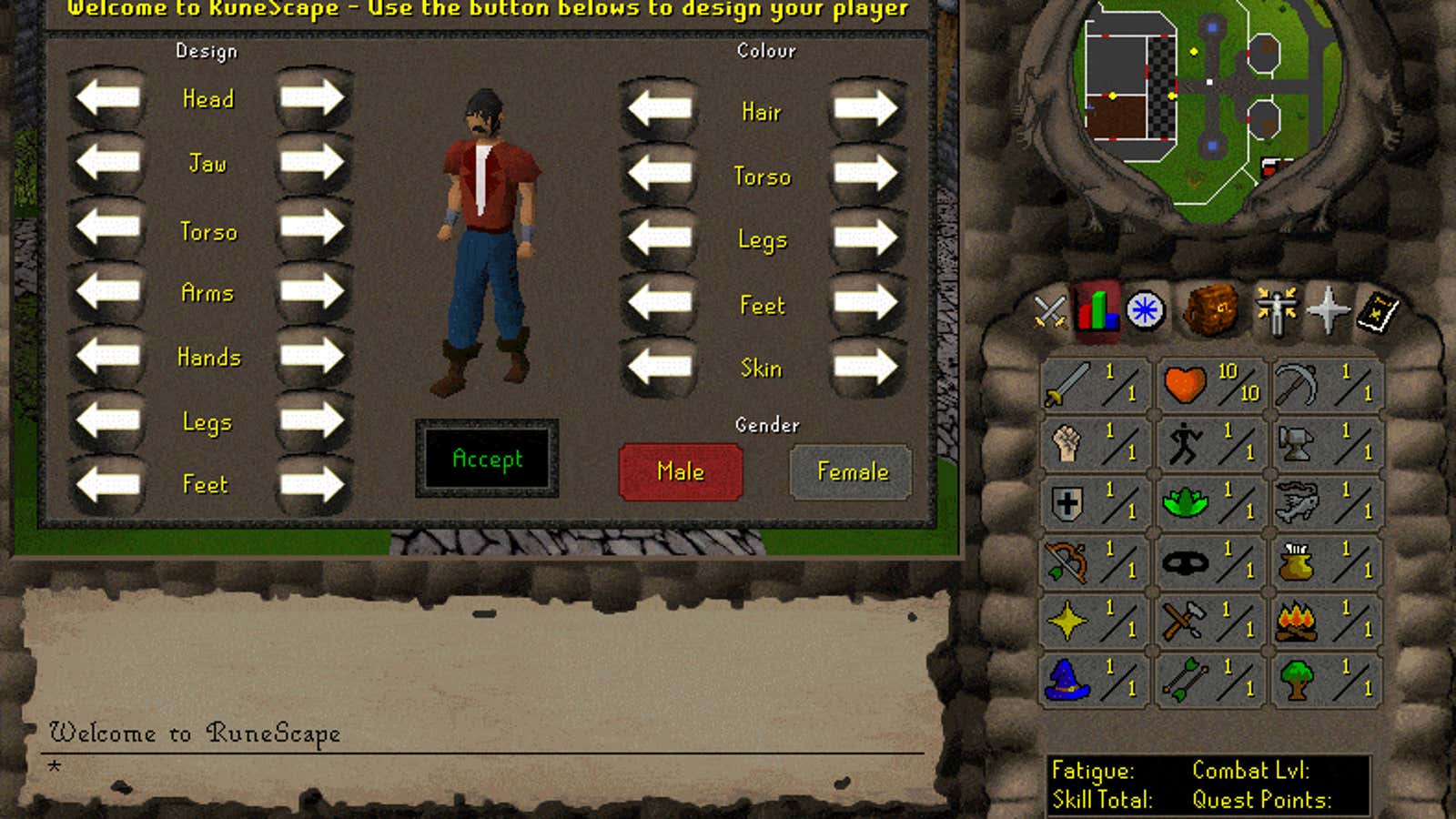

When a person joins RuneScape, they create a character, selecting their name and appearance before a brief training session on “Tutorial Island.” New players can customize various traits such as gender, skin tone, hairstyle, and clothing. For example, I am Slayer201100, a man with spiky turquoise hair.

RuneScape is boundless. You can become a warrior, a priest, a farmer, a fisherman, a blacksmith, a chef—the list goes on. You don’t have to pick just one specialty though; with 27 skills to train, you can build your character however you’d like. You can even resort to petty crime, if your heart desires. I’ve always considered myself—er, Slayer201100—a merchant and part-time mercenary.

Unlike many video games, in RuneScape, there isn’t a specific “goal,” like killing a final boss. Instead, the game presents players with an entire realm. How you amuse yourself is entirely up to you.

The narratives players explore in RuneScape can be silly, like baking a cheesecake, or honorable, like slaying an evil vampire. Some of the game’s most passionate fans have painstakingly written guides for virtually every quest. But players aren’t limited to structured gameplay. They can freely wander around wherever they please, creating their own stories along the way.

My MMORPG, my self

Online games usually feel welcoming to a wide audience because they have something that appeals to everybody. “MMORPGs allow people to play in lots of ways,” explains T.L. Taylor, an MIT professor and ethnographer who has focused on internet and game studies for more than two decades. Some participants may prefer one aspect of the game, like casting spells or mining for ore, while others are drawn in by mini-games, like player versus player (PvP) duels.

MMORPGs grew out of text-based gaming predecessors, like multi-user dungeons, says Taylor. These “MUDs,” created in the late 1970s, had their own roots in tabletop games such as Dungeons & Dragons.

RuneScape’s audience—its players—are people who love fantasy and adventure. They’re the kinds of people who might hang out at Renaissance fairs or particularly enjoy Medieval Times, the jousting and horsemanship show. Kids, in particular, seem to enjoy this creativity. It’s an accessible and non-judgmental environment, where you can be as nerdy as you please.

The MMORPGs of the early 2000s were extra special to young players because they provided a digital canvas. It meant so much to us to customize our characters with a colorful “team cape” and armor of our choosing. These games were something we kids could control, and they felt completely natural. Our characters were like virtual action figures, reflections of ourselves and who we aspired to be. They granted us a sense of personhood.

Every evening, my schoolmates and I would gather online to kill goblins and fire giants while chatting aimlessly. Through RuneScape we enjoyed playing together for hours on end, sometimes teaching one another how to optimize skills. The digital world gave us an opportunity for sustained, collaborative, and consistent playtime. In our collective fantasy, we dedicated hour after hour to our virtual pursuits.

Hunched over clunky computer monitors, we crafted rich digital lives, forged alliances, vanquished enemies, and even pursued professions. Online, there was real action (however simplistic) and it was invigorating because the game could connect you to people across the world.

Digital friendship

MMORPGs gave young players one of the first tools to stay in touch with childhood companions during the early 2000s. Those were the days of dial-up internet connections and landline telephones. Those lucky few who had flip phones faced onerous text messaging limits. We weren’t on Facebook yet, but through online games, children of the internet could circumvent those limits. These nascent social networks gave us license to chat freely and at length, regardless of distance or time—well, at least until we were ordered to go to bed.

For some, games complemented real-life relationships. But for others, it afforded the comfort of anonymity—participants could adopt an online persona different from their real-life one, if they chose to do so. (Of course, this abundant social opportunity comes with significant risks as well. More on that later.)

For adolescents, the chance to test boundaries was invaluable. Moderators appointed by Jagex, RuneScape’s development team, could rein in abusive behavior, like offensive language or harassment. But for the most part, MMORPG communities policed themselves. There was a kinship in playing the game, and while there were competitive elements, being a RuneScape player was a chance to bond with others. At public libraries on the weekend, clusters of 12-year-olds could be found sitting side by side, clicking away for hours on end—usually in dereliction of homework.

Online games extended social opportunities beyond school or scheduled playdates. They allowed people to be part of one another’s world, even at home. Just as we’ve seen the digital erosion of barriers between work and home, online games made friends available at all hours of day or night. Simultaneously, they highlighted the digital divide. Kids who didn’t have computers, or who weren’t allowed to play games, would sometimes feel left out from these online communities.

Some players also took gaming to an extreme, prioritizing computer time over other people or activities.

Taylor noted that connections formed online could be ephemeral or lasting. If a player joined a guild, a semi-formal group of players focused on one skill or activity—or in the case of RuneScape, a “clan”—they might get to know other members over time. Gradually, players may share more intimate details of their personal lives. Taylor refers to this interplay between online and offline culture as “Play Between Worlds,” a phenomenon she studied in Everquest, another popular MMORPG.

Online games also make the boundaries between digital and analog life blurry, Taylor observes—on some servers, players truly “assumed character,” but for many, play became an extension of their real world. One moment, a player could be fighting one of RuneScape’s “Lesser Demons.” The next, they might be asking a friend about the math homework through private chat. (As gaming scholars realized the “role-playing” component of MMORPGs wasn’t as dominant as they once believed, they shortened the term to just “MMO,” Taylor explains.)

Computer games fostered sedentary and physically isolated play, and may have foreshadowed the environment we occupy today, where scores of people live with their noses in their phones, communing with friends and family at a distance rather than interacting with their immediate surroundings. Daily life becomes an interlude to online life, and there’s an ever-present risk that we’ll miss something in the “real world” because we’re preoccupied with our digital selves.

Addiction

Online games can be exceptionally compelling because they give players the opportunity to advance incrementally. That constant feedback—and the leveling up—is exhilarating.

Playing requires patience and persistence, and that can border on addiction. I still remember desperately wanting to achieve level-55 attack and level-55 strength, so I could wield a granite maul. (It’s only a bit embarrassing that those numbers are still engrained in my memory today.) I was overjoyed—and I still am—that I got there! It’s so cool to swing a massive hammer, crushing my enemies, and I look like such a badass carrying it around in the game.

By encouraging players to become invested in the game and rewarding players with small carrots (i.e., higher levels) along the way, RuneScape effectively keeps its fanbase engaged, always striving for more. Although arcade games, such as PacMan, also feature various levels, RuneScape was one of the earliest games to make measurement so explicit—every action helped you acquire experience points. (Fireworks even explode to celebrate each minor achievement.) Later, games like Call of Duty fine-tuned and amplified that feedback mechanism, enticing gamers to dedicate years of their lives to digital achievements. Driven by in-game social status, many players pour thousands of hours—and dollars—into their characters. As long as they enjoy and derive meaning from it, I think gamers, like others, should be able to do what they like (within reason, of course).

Online dangers

MMORPGs indirectly taught players about online safety at an early age. To avoid getting scammed, you had to pay close attention to trading interfaces. Sometimes, a deceitful player would initiate and cancel an exchange. When they restarted the swap, they might offer substantially less gold, or another item altogether. If you agreed to the new deal, you could lose a lot of money—well, gold pieces. Other RuneScape players have said the game spurred their interests in personal finance and accounting.

More perniciously, games could also expose young players to online threats. Anonymity and private messaging could facilitate self-exploration, but they could also be weaponized by online predators—parents of gamers rightly worry. Today, such abuses have spread to more modern games and apps, like Fortnite and Snapchat.

Like the illegal drug trade, online games also spawned massive shadow economies, with bot accounts generating and selling gold pieces for millions of dollars.

Digital Literacy

Today, as I write about digital currencies like bitcoin for a living, the connection to my childhood passion seems obvious. And though the links might not be as explicit for other former players, MMORPGs played a critical role in how we learned to interact online. Really, how different is social media from a role-playing game? We continuously curate ourselves online for friends (Facebook, Instagram) and employers (LinkedIn). And how different are swindles on RuneScape from scams on Twitter? “Send me $5 and I’ll send you $50 back.” (Please, don’t fall for that.) For many of us raised in the early 2000s, our identities and skills as digital natives stem from the games we played as children.

Of course, as gamers have grown older, MMOs have taken a backseat to responsibilities of adulthood—after all, it’s tough to kill dragons while changing diapers. Since many gamers can no longer play for hours uninterrupted, companies have created titles like Fortnite and PlayerUnknown’s Battleground, which allow players to drop in and out as necessary Taylor says. Mobile games in particular have become a dominant part of modern culture, she adds.

Indeed, as a genre of gaming, MMOs have waned in the popular conscience, but they remain a cultural touchstone. They evoke a time when private and public life were not so deeply interwoven, when online gaming was still in its infancy. Games like RuneScape gave children a personalized arcade, a chance to experiment and engage with the internet on their own terms.

As commonplace as online games are today, the lessons from their beginnings should help us be conscious users, aware of the risks and joys of digital life.

So, this is Slayer201100 logging on once more. Anybody want a Rune Scimmy?