The White House is filling in the blanks on its promise to return astronauts to the lunar surface by 2024, requesting another $1.6 billion in funding (pdf) on top of the $21 billion already proposed in US president Donald Trump’s budget for the 2020 fiscal year.

But it is far from clear if Trump or the agency can win over a skeptical Congress. The administration proposes to get the money by repurposing unused funding earmarked for Pell grants, the government financial aid program for low-income college students.

A budget official told the AP that the cuts would not affect current Pell Grant recipients, but the optics of cutting the grants in a time of rising student debt may leave the ambitious moon mission dead on arrival.

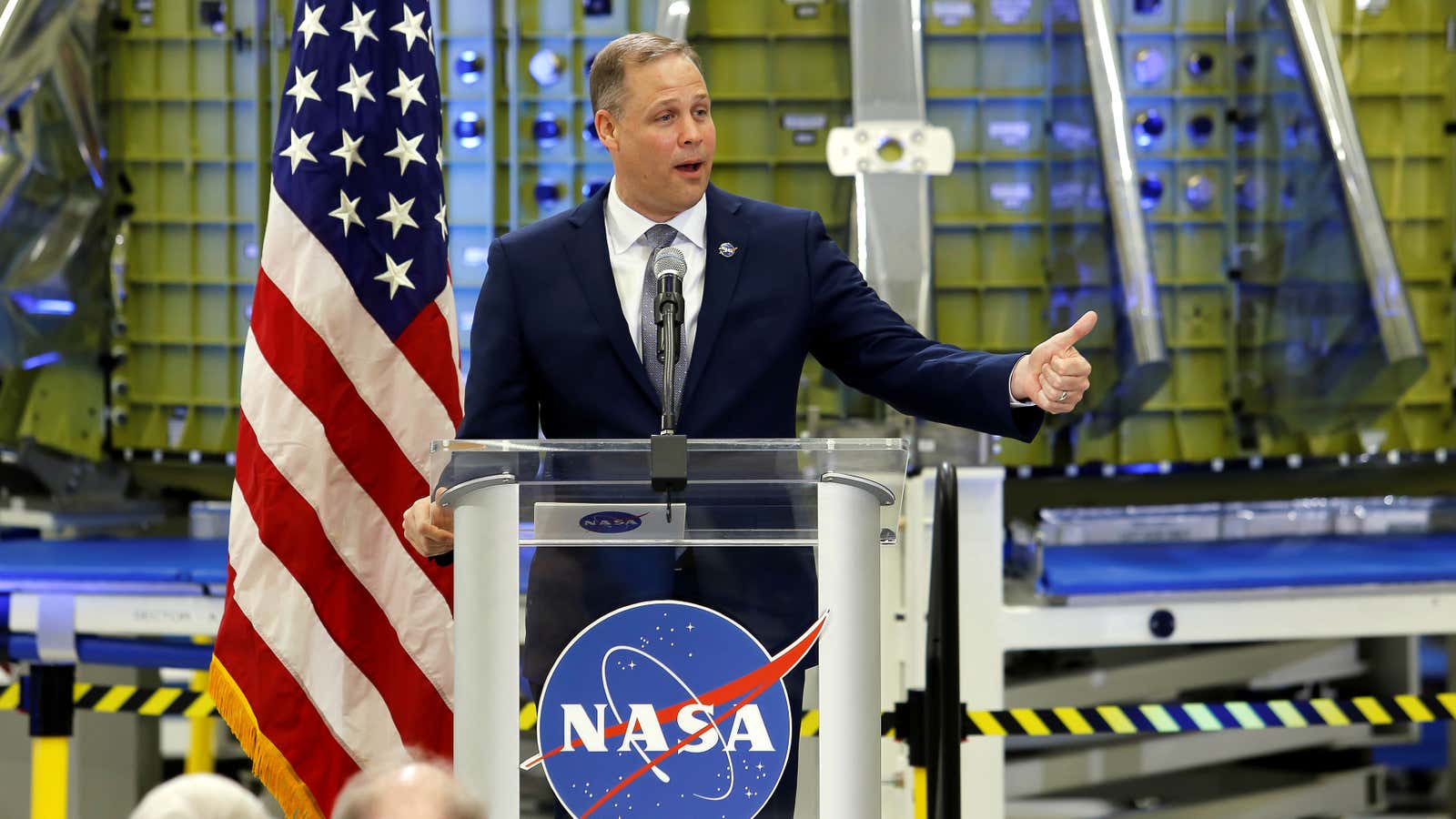

Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, called the tardy budget request a “downpayment” on the expenditure necessary to get to the moon, but could not say how much more would be required in the future. He did say that a rumored total program cost of $8 billion was more than what the agency would consider.

The new moon-landing program is dubbed Artemis, after the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology. The name was chosen in part because the plan is to include a woman in the next human expedition to the lunar surface.

US vice president Mike Pence announced the 2024 goal in March—just weeks after telling Congress the goal was 2028, and well before White House budget officials or the space agency considered how to achieve the deadline.

The amended budget request is “not likely to result in people on the surface in 2024,” Casey Dreier, a policy advisor at the Planetary Foundation, said in a tweet. “If this had been included in the original budget and presented without the rhetoric, it would have been unremarkable.”

The request does not include major programmatic changes that some space engineers believe would be necessary to meet the deadline, like relying on cheaper commercial rockets and abandoning a plan to put a lunar waystation in orbit around the moon.

Instead, the funds would go to complete SLS and Orion, the long-delayed heavy rocket and space capsule NASA hopes will carry humans to the moon. It also includes funds for new technologies that will augment the mission, like tools to convert lunar ice to water, and precursor robotic expeditions to scout the territory.

Its largest line item is $1 billion to purchase a commercially built lunar lander to ferry astronauts to the surface from the orbiting waystation, which NASA calls the Lunar Gateway. Not coincidentally, Jeff Bezos’ space company, Blue Origin, revealed a lunar lander design just last week.

But that $1 billion will only be priming the pump, considering that the two commercial spacecraft for carrying humans currently under trial by NASA—Boeing’s Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon—cost $4.8 billion and $3.14 billion respectively. Those vehicles will travel to low-Earth orbit, not into deep space and to the lunar surface. (Their price tags are still lower than the $16 billion spent on the Orion spacecraft so far.)

NASA researchers, eager to investigate lunar craters and assess the potential of water ice on the moon, back the mission.

The bigger problem for Artemis may be funding an audacious space-exploration program at a time when the administration is pushing deep cuts in other programs.

“I’m skeptical that any Congress, Republican or Democrat, will add billions of taxpayer dollars for a moon program,” says Phil Larson, an assistant dean at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who worked on space budgets in the White House during the Obama administration. “What is needed instead are more innovative ways of doing business with the $20-plus billion in taxpayer dollars given to NASA each year.”

One key voice in the debate will be representative José Serrano, the Democrat who chairs the House committee that approves NASA funding. Born in Puerto Rico, Serrano has been deeply critical of the White House’s stingy approach to disaster relief funds for the island after it was hit by a devastating hurricane in 2017. His support for additional spending will be vital, but Bridenstine, a former lawmaker himself, told reporters that he had not been able to discuss the funding request with Serrano yet.

“It is important for us to understand how important it is to get strong bipartisan support from the beginning,” Bridenstine said, adding that there is “a lot of excitement on both sides of the aisle.”