Barely 10 days after army tanks rolled onto Tiananmen Square and crushed the student protest movement there on June 4, 1989, the Beijing Public Security Bureau issued a most-wanted list of 21 student leaders.

For weeks, students had gathered at the sprawling public plaza in the heart of Beijing to demand democracy, government accountability, and civil liberties like the freedom of press and speech. As many as 1 million people occupied the square, making it one of the largest protests in modern Chinese history.

Then on June 4, 1989, Chinese troops entered the square and fired on civilians. As many as 10,000 were killed, according to a secret diplomatic cable sent at the time.

The majority of activists on that most-wanted list now live in the US, according to information compiled by Human Rights in China, a non-governmental organization with offices in New York and Hong Kong that promotes fundamental rights and freedoms in China.

Here is a snapshot of where some of them are now.

No. 1: Wang Dan

A 20-year-old history major at Peking University in 1989, Wang played a leading role in organizing hunger strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins. He was arrested in July 1989, and later sentenced to four years in prison but was released early in 1993. He was arrested again two years later and sentenced to 11 years for subversion, but was released on medical parole in 1998, after which he left for the US to study at Harvard University, where he obtained a Ph.D in history.

Wang taught for several years in Taiwan at the National Tsing Hua University, and these days focuses his energy on activist work. In 2017, he left Taiwan for the US, where he founded a Washington-based think tank called Dialogue China the next year, with aims “to influence the overseas Chinese international students” and to research ways in which China can transition to democracy.

Writing in the April issue of the Journal of Democracy, Wang took stock of his role in Tiananmen and the meaning of June 4. The protest movement, he argues, ”laid a foundation for democratization in China’s political culture and in popular mindsets.”

Wang said he believes he would do it all over again if confronted with the same choices today. “When one is young, embracing social ideals is not a matter of rational choice, but rather something closer to an emotional necessity,” he wrote. “…That is why I have absolutely no regrets for the price that I have paid. This is my own life choice.”

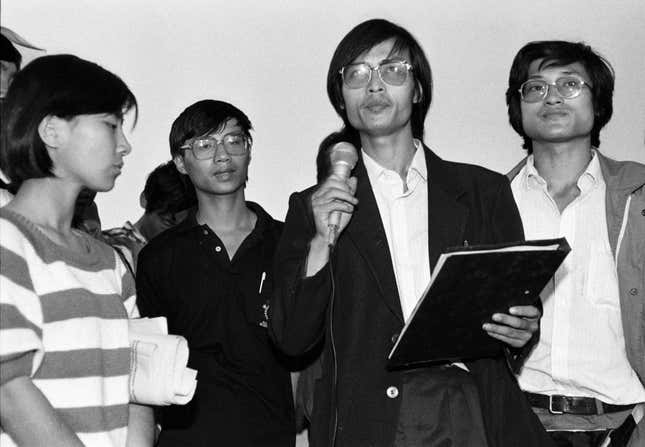

No. 2: Wu’er Kaixi

An ethnic Uyghur, Wu’er was a student leader and freshman at Beijing Normal University in 1989. In a defining moment of the protest movement, Wu’er, who was on hunger strike and dressed in striped hospital pajamas, met with Li Peng, then China’s premier. The meeting was broadcast on television. As Li launched into a paternalistic address to the students, Wu’er interrupted him and proceeded to rebuke him.

“This bold assertion of equality by a pajama-clad student electrified television viewers accustomed to seeing state leaders treated with fawning servility,” wrote Louisa Lim in her book, The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited. “It turned Wu’er Kaixi into a household name, and eventually number two on the government’s most wanted list.”

Wu’er managed to escape to Hong Kong after the crackdown, and from there headed to France and the US, where he enrolled as an undergraduate in the fall of that year. Wu’er moved to Taiwan in 1996, where he has lived since, and is a frequent political commentator. He has tried on multiple occasions to return to China to see his ailing parents, to no avail. In 2016, he tried, unsuccessfully, to run for a seat (paywall) in Taiwan’s legislature.

Speaking at an Overseas Press Club of America event this month, Wu’er recalled what it was like to fight for democracy as a student—despite not knowing very much about the concept. “We never lived in democracy. But how come we fight for democracy?” he said. Well, because we have a damn good knowledge of lacking democracy.”

No. 3: Liu Gang

A graduate of Peking University, Liu was arrested 15 days after the crackdown and sentenced to six years in prison for “counterrevolutionary crimes.” After his 1995 release, he faced police harassment and fled China for the US in 1996. Liu enrolled at Columbia University, where he earned a masters degree in computer science. He subsequently worked at Bell Labs and on Wall Street. After messy divorce proceedings in 2011, activists in the US say they lost touch with Liu (paywall).

No. 4: Chai Ling

A graduate student studying child psychology at Beijing Normal University, Chai played a central role in leading the protest movement. After the crackdown, she went into hiding for 10 months with her then-husband, fellow student leader Feng Congde, before they were both smuggled out of China in a cargo box to Hong Kong. From there they made their way to France, and later to the US, where the pair divorced. Chai went on to earn a master’s in public affairs from Princeton and an MBA from Harvard.

In 1998, Chai founded an educational software company, Jenzabar, with her husband Robert Maginn, who she met when she was working at consulting firm Bain. Chai is now president and CEO of the firm. Over the years, however, Jenzabar has faced numerous lawsuits, including a 2012 suit in which the company was sued for religious discrimination (paywall) for allegedly firing an employee who refused to pray at work.

The lawsuit came after Chai’s dramatic conversion to Christianity in 2009, when she set a new goal of bringing “God’s love and freedom to the Chinese people.” In a 2012 op-ed, she announced that she had forgiven all those who were responsible for the deadly crackdown at Tiananmen Square, including Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng. “Because of Jesus, I forgive them,” she wrote.

No. 5: Zhou Fengsuo

Zhou was a senior studying physics at Tsinghua University in 1989. His sister and brother-in-law turned him in to the authorities the day the most-wanted list was issued, and Zhou spent a year in prison before leaving for the US in 1995. Having previously worked in finance, he is now an activist based in New York. He is also a co-founder of Humanitarian China, a non-profit group that promotes civil society and the rule of law in China.

“There’s a strong feeling of urgency in terms of keeping the memory [of Tiananmen] alive,” Zhou told Quartz. He sees the Tiananmen protests as “the most beautiful moment in China’s history, before the massacre,” and is working hard to reach out to Chinese students in the US.

Looking back, Zhou thinks that he and his peers could have pushed for more power during the protests.

“Even when we were completely in control of Beijing, we were not thinking about political power. That was within reach but that wasn’t our intention,” he said. “We could’ve occupied the radio and television stations. That would have completely changed the picture. It would have defeated the purpose of the military.”

In January, Zhou found out that his LinkedIn page had been censored in China in accordance with the “requirements of the Chinese government.” The website restored access to his profile page, but for Zhou it was a sobering reminder of the Chinese Communist party’s long reach.

“This is how censorship spread from Communist China to Silicon Valley in the age of globalization and digitalization,” he wrote on Twitter.

No. 13: Feng Congde

A graduate student at Peking University, Feng was getting ready to defend his thesis and head to Boston University on a scholarship for his Ph.D when found out that he was on the list of most-wanted student leaders. He went into hiding for 10 months with his then-wife, Chai Ling, and arrived in France in April 1990 by way of Hong Kong. He obtained a Ph.D in the religious sciences department at the Sorbonne University, and wrote his dissertation on Chinese medical cosmology.

Feng currently runs 64 Memo, a website that contains a deep archive of documents chronicling the history of the protest movement. In 2009, he published A Tiananmen Journal: Republic on the Square, detailing the events of the movement. He currently resides in the US.

In 2009, Feng accused the Long Bow Group, a US-based non-profit organization that produces and distributes documentaries about China, of seeking to “intentionally discredit Chai Ling and the student organizers of the movement” in its 1995 film The Gate of Heavenly Peace. Chai’s company, Jenzabar, sued the Long Bow Group in 2007 for defamation and trademark infringement. A court dismissed all of Jenzabar’s claims in 2010.

The irony that both the Chinese government and leading members of the exiled Chinese dissident community criticized the film was not lost on observers (paywall).

No. 18: Li Lu

Li was studying semiconductor physics and economics at Nanjing University and served as Chai’s deputy during the protests. He spent 10 weeks on the run after the crackdown before being smuggled through Hong Kong and onto the US, where he earned business and law degrees at Columbia University. He has since had a highly successful career as an investor and hedge fund manager, and founded Himalaya Capital in 1997. Political activism quickly became a side pursuit.

“Pretty soon, we came to the realization it is just unrealistic to really continue Tiananmen demonstration on the street of New York City,” Li told CNN in 1999.

Li has such stature in finance that some have called him the Chinese version of Warren Buffet. Earlier this year, Buffet’s right-hand man, billionaire investor and vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, Charlie Munger, said that the only person he would trust with his money besides his boss is Li.

“I’m 95 years old. I’ve given Munger money to some outsider to run once in 95 years,” Munger said. “That’s Li Lu.”