Russ George, a businessman and self-styled “plankton evangelist”, and his team of scientists dumped 100 tons of iron dust from a fishing boat bobbing in the Pacific.

It’s part of an audacious plan to fight—and profit from—global warming by altering the ocean’s chemistry to trigger massive growths of plankton, the tiny animals floating in the sea. These plankton blooms consume carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and then, in a few weeks, die, sinking to the bottom of the ocean and taking the carbon with them. And, in theory, George sells carbon offsets to companies wishing to meet emissions requirements.

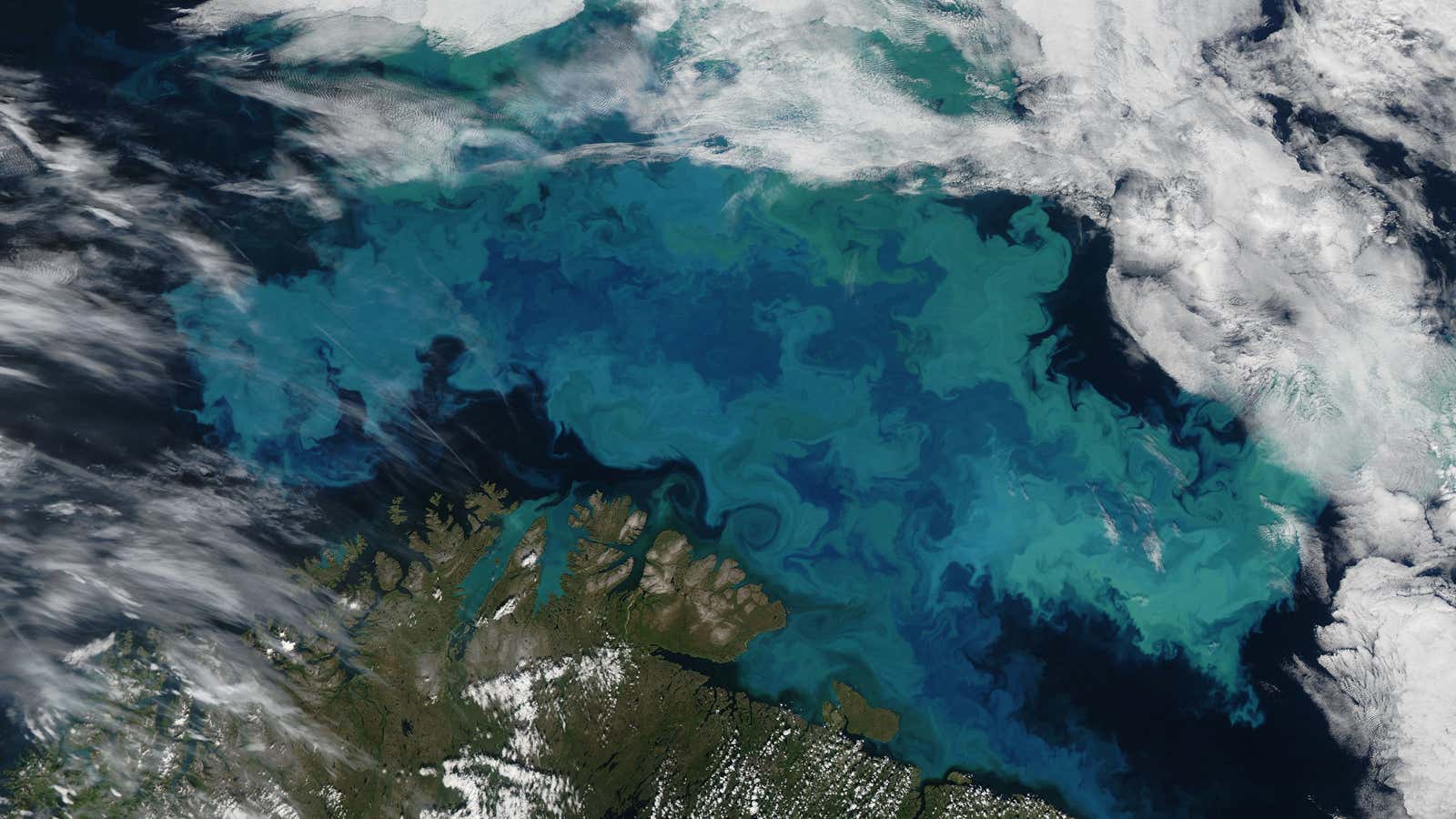

The Guardian investigation that revealed George’s latest escapade said that satellite photos appeared to confirm the creation of a 10,000 square kilometer plankton bloom.

George says this is the world’s largest geo-engineering experiment, and reports that he received more than $1 million from an indigenous group. He told a village of the Haida nation that the project would enhance salmon fisheries 200 miles west of Haida Gwaii, an island off the coast of British Columbia, by filling in for dust that no longer blows from the Gobi desert. (He describes his plans starting at about 30 minutes into this video.) He also expects to earn about a million tons of carbon offsets.

George, who has also dumped iron with the musician Neil Young in his sailboat Ragland, had attempted a similar project near the Galapagos islands in 2007, but criticism from environmental groups led the Ecuadorean government to ban his vessels; the Spanish government forbade him from dumping near the Canary Islands as well.

Though scientists estimate that iron-seeding at scale could contain about 1 percent of global emissions, they are also concerned about the unexpected consequences of dumping so much of anything into the ocean. Some fear that the process could actually rob the ecosystem of nutrients or merely depress plankton production elsewhere, eliminating any real carbon offset.

While the idea of altering the global environment to counter global warming has been kicked around—especially as agreements on capping carbon emissions have foundered—governments have been reluctant to back those projects because the potential for surprises is so high. But George is just one of several entrepreneurs and companies hoping to turn massive projects like iron-seeding, pumping sulfur dioxide into the sky, or creating building-sized carbon filters into lucrative business opportunities.

In the near-term, though, George’s biggest challenge isn’t climate change, but international law: The project is likely to violate conventions against dumping waste and altering biological diversity at sea. Even this week, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity is meeting in India, and banning experiments in geo-engineering is on its agenda.

Without more evidence, it’s easy to scoff at George’s plans. But if governments continue to show limited interest in acting on climate change, maybe a man dumping metal in the ocean will turn out to be an environmental pioneer.