In the jungle of online content, the house cat is king.

Felines cuddle, scowl and ninja-swipe their way through BuzzFeed, Huffington Post, and Reddit. Maru, a portly Japanese tabby with a tendency to get his face stuck in cups, has been viewed 236 million times on YouTube. And when Google’s X laboratory simulated a human brain last year with 16,000 computer processors that trawled 10 million random images from YouTube, the first thing that the electronic hive brain did was teach itself the concept of a cat.

A New York-based media company, Klooff, is trying to monetize this insatiable appetite for kitties—as well as puppy, parrot, and bunny cuteness—on a new image-based online media channel that also doubles as an open social network. Klooff’s CEO says his company has cracked the code of generating viral content—and has cut out the middle man.

“It is a crowd-sourced approach to pet media,” says Alejandro Russo, Klooff’s 25-year-old Chile-born CEO. “There’s a big group of people who love their pets, me included. And there’s an even bigger group of people who love watching pet stuff on the Internet… We decided to create an actual channel for that because it didn’t exist.”

The irony here is that pets (and literally, Pets.com) were once the symbol of the dot-com bust. Certainly others have tried in more recent years—there is the Fluffington Post, for example. Klooff tries to be different with an active curation process, an emphasis on social media, and a mobile-first approach.

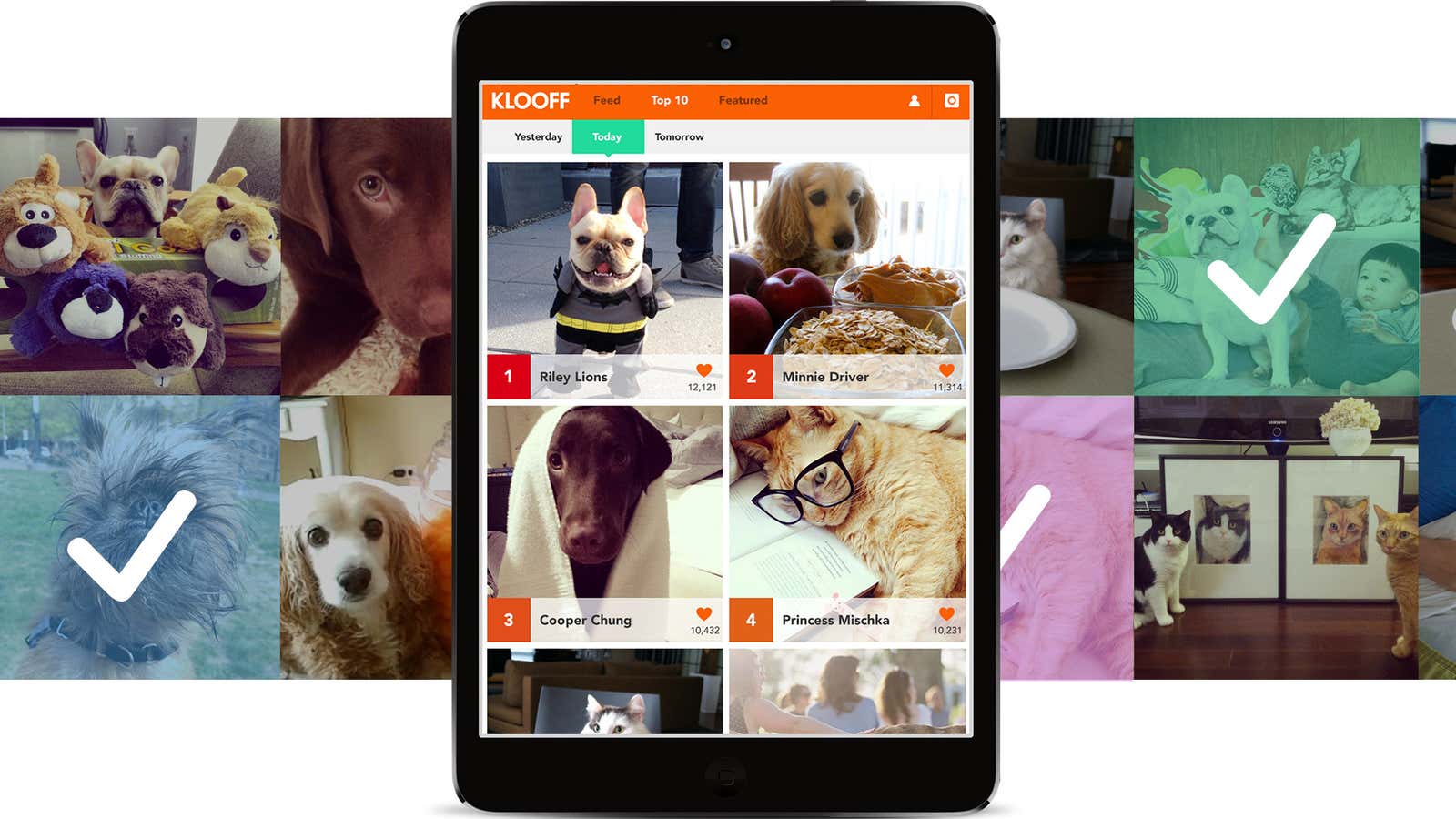

On the site—now in beta as an iPhone app—a member responding to Klooff’s invitation to “celebrify your pet” and “make him America’s favorite” can create a profile for Fido and upload videos, gifs and photos to the network. Once the site is fully launched across mobile devices and web browsers in January, the cute-hungry hordes will be able to view Fido’s naptime quirks, trapped-in-a-container episodes and hijinks, and to vote on and share the content.

Cute pet voyeurs will be able to see a feed of recently uploaded content, or to skip straight to the best of the multimedia litter–calculated based on algorithms, views and votes, and packaged in lists such as the day’s cutest canines. In Beta alone, Klooff (an invented word that means “happiness” in petspeak, according to Russo) already has an active user base of content creators of more than 15,000.

Klooff has figured out how to leverage a plentiful resource, says Geoff Cook, a partner at Base Design and a Klooff advisor: people’s eagerness to show the world their pets’ cuteness. And unlike, for example, baby photos, there are no privacy issues; the proud owners of that mewling bulldog pup are eager for as many views as possible.

“Principally, Klooff is a media company that can generate massive amounts of page views using free content,” Cook says. Those clicks will attract advertisements, Klooff’s founders hope, which will be integrated into the site in native formats and sponsored content.

Currently, about 2% of all social links are “some cute fuzzy animal,” according to Bitly’s chief scientist, Hilary Mason.

Currently, many people discover their new favorite mean-mugging cat or dancing dog on curated lists that are compiled, headlined and captioned by paid journalists. On Klooff, algorithms that analyze responses to the content replace the work of an editorial staff. Along with Russo and his two cofounders, Mario Encina, and Jane Chung, the company employs a team of 13 engineers.

It remains to be seen whether this algorithmic Darwinism will succeed. Gawker wunderkind Neetzan Zimmerman, renowned for his ability to create instantly viral content, has expressed some skepticism about the algorithmic approach—and about cats. In a recent Wall Street Journal profile, Zimmerman was asked about whether a machine or formula can predict virality:

He doesn’t think so. While machines have lots of data, Mr. Zimmerman says they wouldn’t be very good, yet, at intuiting subtle, collective changes in human preferences as quickly as he can. “I’m following the big story arcs online, like in a soap opera,” he says. “Like within a trend of cats, different cats will have moments where they’re popular: Grumpy Cat is not popular now, but maybe it’s Lil Bub.” Zimmerman doesn’t track this with a spreadsheet or any formal system. He just sort of feels the changes, on a day-to-day basis, as the viral news turns.

If Klooff’s approach proves successful, it could have wider implications than the world of pet videos. Indeed, traditional media companies are experimenting with algorithmic publishing—for example, The Guardian, which has started a robot-generated version of the newspaper, The Long Good Read, and Narrative Science, a company that produces algorithm-derived writing. But creating revenue may be more of a challenge than Klooff’s co-founders might expect.

Still, Cook remains optimistic about Klooff’s prospects. He is working with the company to establish Klooff as a brand, he says, rather than just a product. This, he hopes, will bring in more moneymaking opportunities—new products, licensing opportunities and brand partnerships. “Klooff is inherently about generating happiness,” he wrote in an email. “Can you imagine the number of companies that will want to align themselves with such a positioning?”