The World Health Organization (WHO) reports there are more than 112,000 confirmed cases of measles worldwide, as of this month—a 300% increase from the 28,124 cases this time last year.

The actual number of people afflicted is certainly higher. The WHO only collects data on cases confirmed through lab testing or clinical visits. There are likely thousands who never seek medical attention.

The virus causes severe flu-like symptoms and a characteristic bumpy rash. There is no cure, and the best course of action is to try to treat symptoms as they come. Usually not fatal in wealthy countries, it can cause permanent loss of sight. In poorer countries, the risks of dying are much greater.

Why this year’s measles outbreak is bigger

There are two main factors. First, there’s been a global trend of skeptical parents failing to get their children vaccinated due to false concerns about their safety. Measles has become largely preventable through two shots administered during childhood. In 2000, the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC) said that the virus had been eliminated in the US. Yet there have been more than 700 cases recorded in 22 states this year.

The WHO estimates that globally, only about 85% of people have received a first vaccine dose and only 67% have received the second to make them fully immune. To stop wide transmission of the virus, 95% of people need to have the vaccine. Measles is a highly contagious, spread through direct contact with someone who has it. “The only reservoir for the measles virus is people,” James Goodson, a senior measles scientist at the CDC, told NPR. Global travel only increases the chances of the virus spreading further.

The only way to stop the current outbreak is to make sure more children are vaccinated, Goodson told NPR. The trouble is many countries can point to reasons for why vaccination rates may be low—from lack of infrastructure to safely distribute vaccines, to distrust in vaccines and public-health care overall, or disruptions caused by conflict.

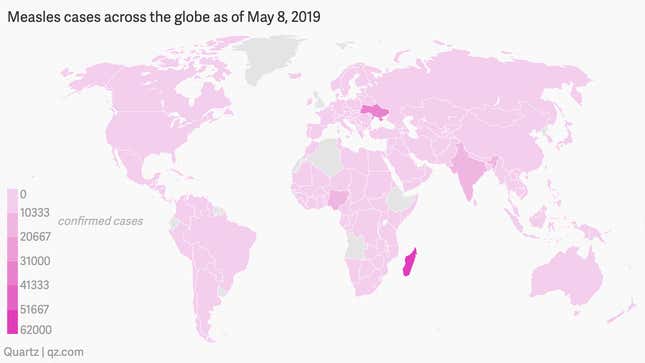

Where measles has hit hardest

The epidemic is worst in Madagascar, where poor resources, limited medical care, and malnutrition make the outbreak more widespread and deadly. There are 62,000 confirmed cases, and estimates suggest there are actually twice as many. Thousands of children have died. Only about 58% of the country’s 25.5 million people are vaccinated. The WHO says that cases are finally falling after it launched a campaign last month to get children vaccinated.

The Philippines is also having a severe outbreak, with more than 33,000 cases. Like the US, the Philippine government had assumed the virus was eliminated. However, distrust of vaccines—likely sparked by a hasty campaign to promote a vaccine against Dengue fever that has can have fatal side effects for some children—has meant that vaccination rates against measles plummeted. The Dengue vaccine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and recommended to all children by the WHO, despite the safety concerns. After hundreds of children died due to complications, the campaign was stopped. But the number of Filipino parents who believe vaccines are critical for their children’s health fell from roughly 80% to 20%.