The Nile and its waters have historically been the lifeblood of Egypt. The country’s population occupies just 5% of the land, almost all of it along the Nile. But Egypt’s scorching deserts beyond the Nile delta hide a bounty: vast groundwater resources, which have usually been deemed not worth tapping.

Recently some farmers have begun to move outwards into the western desert to exploit the vast expanses of land, using diesel-powered pumps to pull up the groundwater for their crops. Diesel is cheap (the government subsidizes it) and the pumps run 20 hours a day. But they are noisy and polluting, and transporting diesel to these remote areas is costly and hard. “A logistical error in providing the diesel could result in powerless pumps, and therefore the loss of entire crops,” explains Xavier Auclair, founder of KarmSolar.

Four years ago Auclair, an engineering graduate, was based in his home country of France working for a strategy consultancy. He did well financially and progressed rapidly up the company ladder. But a few years in he found himself sitting in a closed-door meeting with an investment firm. “600 people were to lose their jobs due to that meeting’s decisions,” he said. After the meeting he resigned, and spent the next four months sailing halfway across the world, eventually moving to Egypt and learning Arabic. In reaction to what he had seen at the job he left behind, he decided to use his engineering training to pursue a “more moral” line of work. He began investigating the potential of renewable energy products, and with Ahmed Zahran, a former colleague, he started Karm Solar.

KarmSolar hopes to persuade the farmers to swap their diesel for solar power. Egypt is considered a “sun belt” country, lying in an area that receives 1970-3200 kilowatt-hours per square meter (kWh/sq m) of solar energy each year. By comparison, India receives between 1600 and 2200 kWh/sq m per year. The photovoltaic cells convert the sun’s energy into an electric current. (A kilowatt-hour of electricity powers a standard 100-watt bulb for 10 hours, though in the conversion from solar energy to electricity some of the energy is lost.) This can then be stored in batteries or used to power the pumps.

Although Egypt has more than its share of hot sunny days, the majority of Egypt’s renewable-energy solutions have been in the fields of hydroelectricity (Aswan dam) or in wind turbines (the recently built 200 megawatt wind farm in the El Zayt Gulf on the Red Sea). In another country the government might have systems in place to help a company such as KarmSolar. But in Egypt “they are actually more of an obstacle to us,” said Auclair. “They are subsidizing their fossil fuels to such an extent that we are effectively being priced out of the competition. This is one reason why we are moving off grid.”

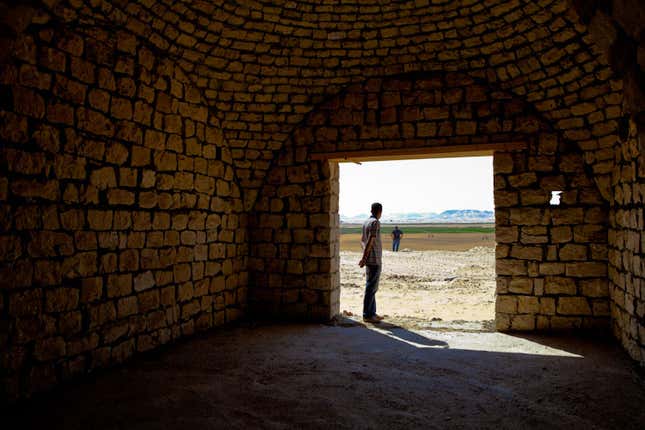

KarmSolar has been commissioned to create a proof-of-concept “model farm” within a larger farm in the western desert, over 200 miles from Cairo. KarmSolar and its architectural partner, Green Architecture & Urbanism, spent days in the desert looking for possible sites. They want to design an area that would incorporate some 700 sq m of solar panels and a further 300 sq m for the buildings and workshop, to be built using locally procured materials.

Another partner of KarmSolar’s is WorldWater & Solar Technologies (WWST), a company based in Princeton, New Jersey, which is helping it improve its technology. As farms grow, technological hurdles appear. If a farm requires more than 20kW of solar power for its pumps, the bigger batteries needed to store the energy become much more expensive to produce and maintain, thus pricing the energy out of the market.

One of the problems with working off the grid is that every water pump needs to be designed to suit the conditions where it will be used—variations in the wind and the depth of the water table, for instance, must be considered. WWST helped KarmSolar write software that designs the farms and makes projections of their efficiency, overheads and returns, so they can pitch to potential investors.

Changing a country’s established methods takes time. Because the model farm is being built at a farm that already exists, Auclair is under no illusion that this first project will be everything he imagined. The pumps will still be using diesel power 60% of the time (due to restrictions, they can only use solar power on one well; the extra water required comes from diesel pumps). They will also be unable to implement a water-efficient, hydroponic “closed water system”; the rotary irrigation system that farmers are used to and prefer loses some ground water to evaporation.

The end goal is to one day create an entirely sustainable community off the grid. In the process Auclair hopes to create a cleaner, more sustainable Egypt by using the country’s massive quantities of land, groundwater, and sunlight, allowing farmers to be less tied to the crowded boundaries of the Nile.