On Monday (June 3), an emotional, three-year inquiry into Canada’s treatment of aboriginal women came to an end—though the process of national reconciliation is only just beginning.

In 2016, the government of Canada launched a National Inquiry to investigate the murders or suspicious disappearances of about 1,200 indigenous women and girls between 1980 and 2012. The process opened up deep-seated national wounds: According to The New York Times (paywall), “more than 1,500 families of victims and survivors testified in emotional hearings across the country.”

Now, the National Inquiry has released its conclusion in the form of a two-volume report (pdf) that called the violence against indigenous women and girls a “deliberate, often covert campaign of genocide” and blamed the Canadian government and Canadian society for it.

Specifically, the report linked violence against indigenous women and girls with “systemic factors, like economic, social and political marginalization, as well as racism, discrimination, and misogyny, woven into the fabric of Canadian society.” It also said that “colonial structures” enabled the violation of indigenous rights, like the residential schools that the Canadian government forced thousands of indigenous children into attending in order to “break their link to their culture and identity.” In these schools, many children “were prey to sexual and physical abusers.” Finally, the report focused on the lack of security for indigenous women and girls. “The fact that there is little, if any, response when Indigenous women experience violence makes it easier for those who choose to commit violence to do so, without fear of detection, prosecution or penalty,” it said.

Experts say (paywall) the trauma of this repression and abuse has contributed to “persistently high rates of poverty, drug abuse, alcoholism, domestic violence and suicide” among indigenous populations, according to The New York Times. Indigenous women and girls in Canada are three to four times more likely to go missing or be murdered than their non-native peers. And indigenous people are more likely to be poor, incarcerated, die young and commit suicide.

“Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA [Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual] people in Canada have been the targets of violence for far too long,” reads the report. “This truth is undeniable. The fact that this National Inquiry is happening now doesn’t mean that Indigenous Peoples waited this long to speak up; it means it took this long for Canada to listen.”

After receiving the report in an official ceremony, prime minister Justin Trudeau promised to “conduct a thorough review” and create a National Action Plan to address the violence. He said, “To the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls of Canada, to their families and to survivors—we have failed you.”

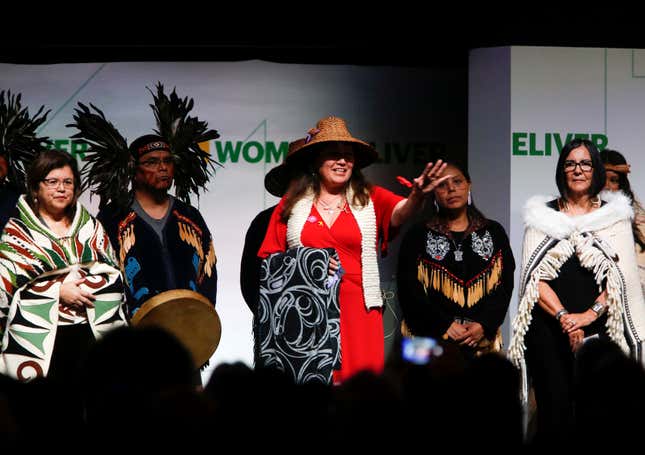

Indigenous activists present at the Women Deliver conference in Vancouver this week—where Trudeau spoke at length about the results of the inquiry—celebrated the release of the report but emphasized how much work remains to be done to reverse the effects of what the inquiry called “cultural genocide” enacted upon First Nations.

“What hinges on the disappearance of indigenous people … is the chasm that has happened in families,” said Carol Couchie, a midwife from North Bay, Ontario and co-chair of the National Aboriginal Council Of Midwives (NACM), a nonprofit group that advocates for indigenous midwifery. ”Family structure has broken up, tribal structure has broken up, leadership has been weakened, the self-esteem has been reduced to on the ground, and these things have all affected our ability to care for young people, to care for women.”

According to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, most of the violent crimes against indigenous women are perpetrated by individuals within their own communities. In a report published in 2015, they said that while indigenous women make up just 4.3% of Canada’s women, they are 16% of female homicide victims and 11% of missing persons cases involving women. Couchie and fellow NACM co-chair Claire Dion Fletcher said the root of this violence could be traced back to the erosion of indigenous culture. “Our values, our culture, our languages; all these things have been torn up and removed, and along with that went these women,” said Couchie. “There’s a hole in our souls that’s a mile-wide.”

“Nobody really understands what they took,” she added. “We are barely, in some cases, beginning to understand it ourselves.”

Throughout the three-year-long process, skeptics in indigenous communities had voiced concerns that the inquiry was not sufficiently transparent and that it would not lead to concrete change. Marion Buller, the chief commissioner of the inquiry and a former indigenous judge, told Quartz she “was aware of the criticisms.” “But it really comes down to our final report,” she explained. “That’s what’s important; that we properly and accurately recorded the truths that families and survivors shared with us, that we accurately and thoroughly did our research and properly stated what experts and knowledge-keepers told us, that we made the proper findings of fact, and that our calls for justice are grounded in our findings of fact.”

The report directed 231 “Calls to Justice” at the government, social-service providers, the private sector, and Canadian people intended to remediate the persistent inequalities between indigenous and non-indigenous Canadians and safeguard and promote indigenous culture and people. Buller said she was “hopeful” that these recommendations would be implemented. “First of all, the activists and frontline people who worked very hard to make this national inquiry even happen aren’t going to give up,” she explained. “The families and survivors who came forward and said their truth are… going to hold governments accountable.”

What happens next will be a litmus test for Canada’s process of national reconciliation. In its final report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission committed to ”restore what must be restored, repair what must be repaired, and return what must be returned.” And indigenous activists like Couchie and Fletcher will be waiting to see them do just that.

This story is part of How We’ll Win in 2019, a year-long exploration of workplace gender equality. Read more stories here.