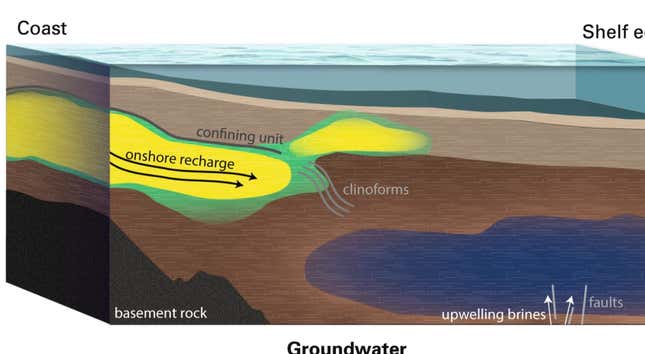

Thousands of years ago, glaciers covered much of the planet. Oceans receded as water froze in massive sheets of ice blanketing the North American continent. As the ice age ended, glaciers melted. Massive river deltas flowed out across the continental shelf. The oceans rose, and fresh water was trapped in sediments below the waves. Discovered while drilling for oil offshore in the 1970s, scientists thought these “isolated” pockets of fresh water were a curiosity. They may instead prove to be a parched world’s newest source of fresh water.

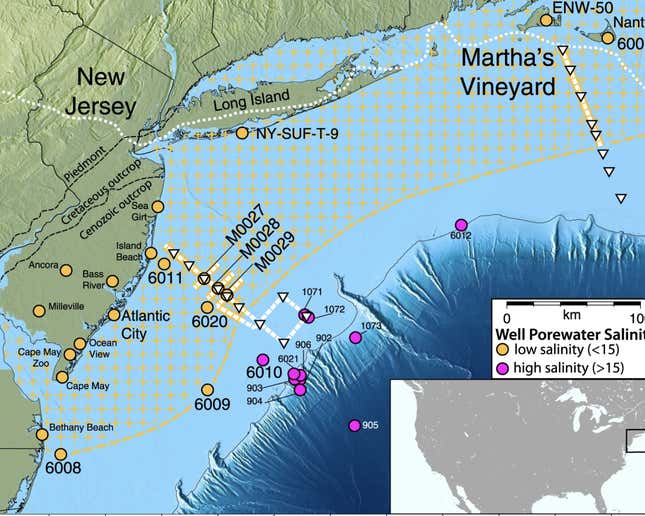

As told in the latest issue of the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports, scientists from Columbia University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution spent 10 days on a research ship towing electromagnetic sensors from New Jersey to Massachusetts. By measuring the way electromagnetic waves traveled through fresh and saline water, researchers mapped out fresh-water reservoirs for the first time.

It turns out the subterranean pools stretch for at least 50 miles off the US Atlantic coast, containing vast stores of low-salinity groundwater, about twice the volume of Lake Ontario. The deposits begin about 600 ft (183 m) below the seafloor and stretch for hundreds of miles. That rivals the size of even the largest terrestrial aquifers.

“We knew there was fresh water down there in isolated places, but we did not know the extent or geometry,” said lead author Chloe Gustafson, a PhD candidate at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, according to Phys.org. “It could turn out to be an important resource in other parts of the world.”

The size and extent of the freshwater deposits suggest they are also being fed by modern-day runoff from land—and may exist elsewhere with similar topography.

The water is not pure terrestrial fresh water, which contains salt concentrations of less than one part per thousand. Near land, the undersea aquifer has concentrations close to pure fresh water. Toward its edges, it may reach 15 parts per thousand (about half that of seawater). That’s still valuable. Desalination plants could easily turn that into drinkable water.