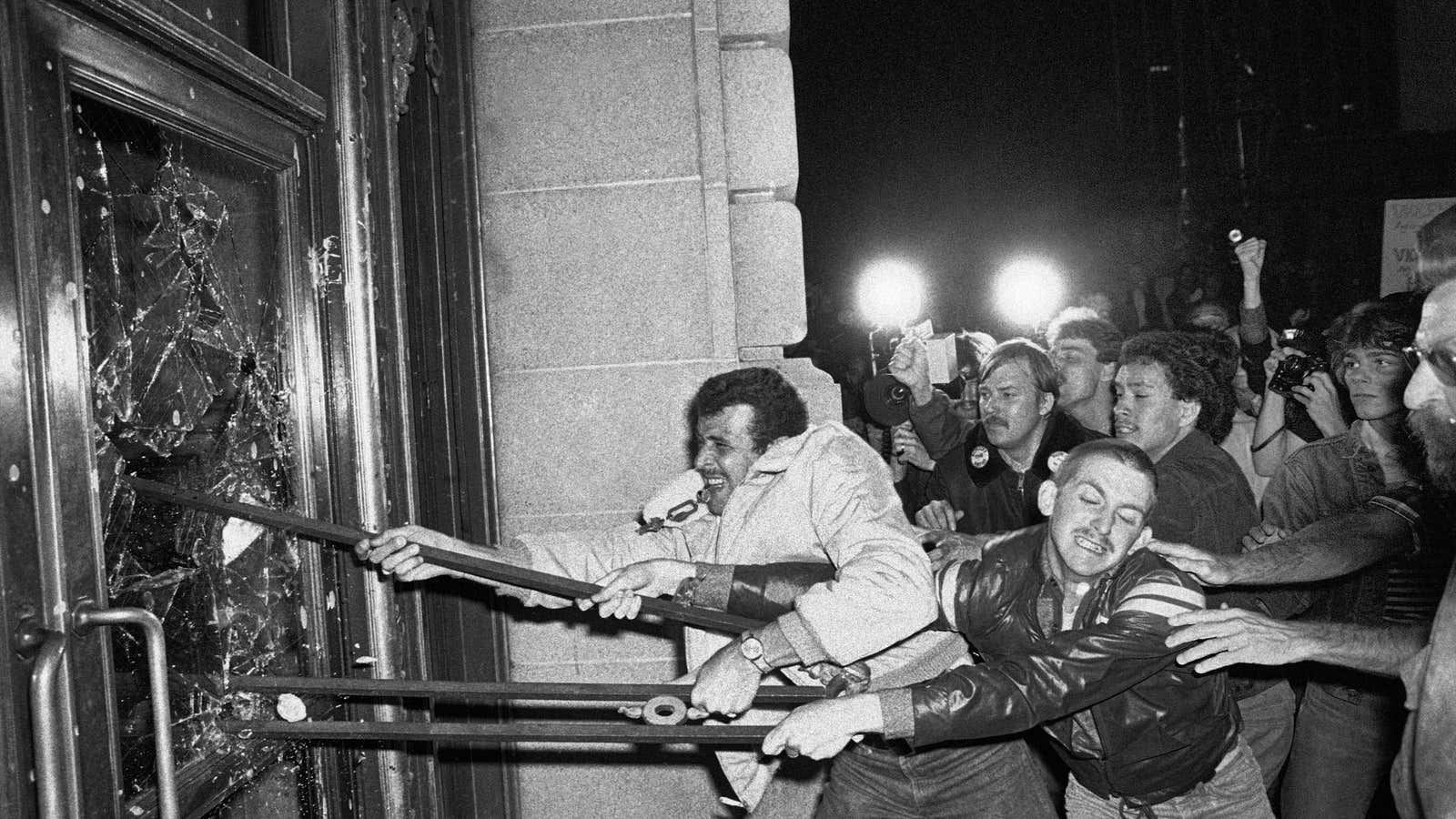

In the first hours of June 28, 1969, the NYPD raided New York City’s Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in the West Village that opened two years earlier. At the time, police often targeted gay bars. They would threaten to arrest patrons and disclose their identities, and demand fines for specious violations.

But this time was different: Instead of complying with the police, the customers started a legendary riot. The protest continued for two days and is now remembered as an important milestone in the fight for LGBTQ rights. It was not pretty. It was violent, a reflection of the tensions that brewed for years between the queer community, the police, and the establishment at large.

Five decades later, the whole of NYC seems to have turned into a rainbow as it marks Pride Month. The city (and many others around the world) is celebrating its LGBTQ community this month through a series of initiatives and parties. Even New York police stations now proudly display their festive support of the LGBTQ community.

These annual celebrations culminate in a parade, which has been held on the last Sunday of June since 2,000 people marked the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots in 1970. That first celebration was known as the Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day.

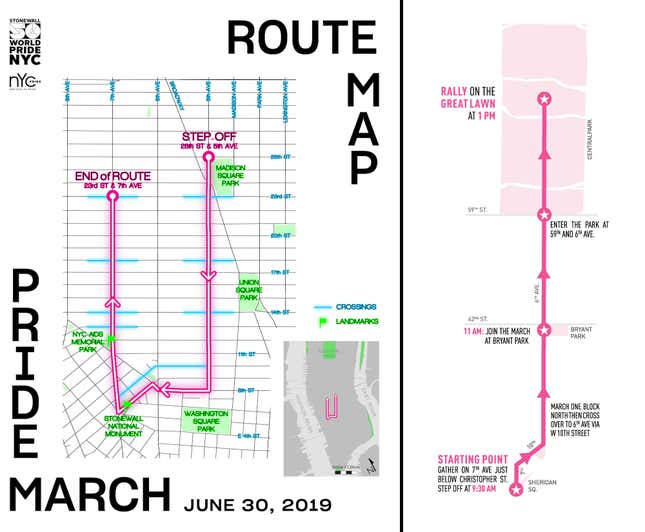

But this year, on June 30, there will be two marches: The NYC Pride march—which with 4.5 million expected participants is believed to be the largest pride parade in the world; and the the Queer Liberation March and rally, which is expected to draw tens of thousands.

Organized by Reclaim Pride, the smaller march wants to be an expression of the more radical soul of the LGBTQ community, and to pay homage to the legacy of Stonewall by remembering its riotous, anti-establishment nature. It wants to be more than just a celebration, and it does not want to be an event that is increasingly a parade of corporations, as its organizers claim NYC Pride has become.

Both marches will pass by the Stonewall Inn, but while NYC Pride will set off at noon from the Flatiron district, the Reclaim Pride march will follow the route of the original 1970 march, starting at 9:30 am from Christopher Street, and ending with a rally in Central Park, where that first march held a “gay be-in.”

The Resistance Contingent

A coalition of dozens of LGBTQ groups, Reclaim Pride is, in a way, a product of the Trump administration. After the 2016 election, some of the more radical and progressive groups and members within the LGBTQ community organized what they called the Resistance Contingent. Their goal was to resist the threats posed by the current administration on issues related to the queer community, as well as other intersectional matters.

This radical contingent rejects the increasingly corporate nature of NYC Pride. These days, in order to march in the main parade, you must join as part of an organization or business. And, in a move the Resistance Contingent sees as a surrender to police, the parade is now held behind barricades, preventing casual participation. For many, the parade, and NYC Pride more broadly, is losing some of its original meaning.

“The LGBTQ community is one of activism and creativity,” said Natalie James, one of the co-founders of Reclaim Pride and an organizer with the Democratic Socialists of America. But by becoming more mainstream, pride marches have allowed corporations to use LGBTQ identity to “pinkwash” their image. She notes, as an example, weapons manufacturers marching in support of LGBTQ rights.

After marching with NYC Pride in 2017 and 2018, the Resistance Contingent eventually formed Reclaim Pride and decided to organize its own event.

Why two marches?

“We don’t have specific demands, it’s a symbolic and performative action,” James said.

The two parades represent two different souls within the gay movement. It’s comparable to the Democratic National Convention and Indivisible: One is established, mainstream, effective, supported by big organizations, and open to compromise. The other is much younger, radical, won’t take corporate sponsors, and isn’t afraid to displease some power brokers.

Through the years, NYC Pride—like many other LGBTQ marches around the country and the world—abandoned much of its radical roots, shedding its more feisty elements to become the fun party millions are now used to attending. It’s done wonders for the acceptance and support of the Pride message from the broader community. “Millions of people come to the march,” Cathy Renna, a longtime LGBTQ activist and spokesperson for NYC Pride, told Quartz.

But Reclaim Pride is more interested in maintaining the original spirit of the Stonewall riots and Liberation Day than what they see as an effort to assimilate into a predominantly heteronormative lifestyle and a neoliberal social order. “We hope it’s a global moment of re-radicalizing pride and queerness,” James said.

Reclaim Pride does not accept corporate donation, allows individuals to attend the Queer Liberation March independently from their organizations, and aims to be an affordable and open to all in the spirit of the early marches. Further, there is no official NYPD representation, which James says would allow the police “to market itself as a LGBTQ friendly employer while brutalizing transgender people, especially of color.”

Being diverse—together

Naturally, NYC Pride sees things differently. Its organizers reject much of Reclaim’s criticism. Renna said the LGBTQ movement is not a stranger to internal disagreements. In fact, she says different currents have been part of the community from the time of the Stonewall riots. Other parades and protest marches have amicably coexisted alongside the main event for years, too, including the Dyke March (scheduled for June 29), the Trans Day of Action (June 28), or the Drag March (June 28). “Some persons are more mainstream, others are less so—different parts of our community care about certain issues more than others,” she said.

While acknowledging that Reclaim Pride is right in its criticism of some corporations, and even the NYPD, NYC Pride doesn’t think excluding all corporate sponsors, and indeed banning LGBTQ members of the police from marching, is an effective or fair strategy. “They are not allowing queer cops to march; and what about queer veterans—do they not matter?” Renna asked. Allowing LGBTQ members of the police to march in their uniform, she said, can coexist with demanding that the police stop brutalizing transgender people and people of color.

Similarly, corporations aren’t just there to “pinkwash” their reputations, Renna said. NYC Pride demands their sponsors show actual commitment to the cause of LGBTQ rights, she pointed out.

“We demand a lot more than showing rainbow flags in June,” she said, adding that the corporations supporting NYC Pride all give back. Further, she says, corporations supporting pride are important for the LGBTQ community around the country. “It makes people outside the New York bubble feel seen.” Young queer people in conservative environments, for instance, could find comfort and strength in a Target decked out for Pride. The queer community depends on businesses financially, but also ideologically: In many cases, she says, business have been faster to move their internal policies to be LGBTQ-friendly than the government, and corporations have the power to put effective economic pressure on lawmakers, by threatening boycotts of cities or states that don’t give equal rights to queer people, for example.

The rights, respect, and visibility that the LGBTQ community has achieved would have been unimaginable at the time of Stonewall, Renna said. But the fight is still very much ongoing. Much of the progress made in the past few years, particularly when it comes to the rights of transgender people, has disappeared under the current administration, and Renna thinks this is the time to join forces. “I find the divisiveness to be not helpful,” she said.

For Reclaim Pride, however, the issue isn’t just one of stating differences from the mainstream march. It is instead about drawing attention to a different way of celebrating pride, outside capitalist dynamics and interests. “I like to think that we are part of the zeitgeist of the time, which is one against the neoliberal order,” James said. “Now is a time when issues of social justice are rising and I think and hope we are part of that.”