We charted the ideological lines along which each Supreme Court justice voted

The US Supreme Court last week wrapped up the 2018 term, having decided on the merits of 72 cases. These matters yielded many opinions, revealed surprising alliances, and proved you never know how the justices will vote.

The US Supreme Court last week wrapped up the 2018 term, having decided on the merits of 72 cases. These matters yielded many opinions, revealed surprising alliances, and proved you never know how the justices will vote.

New data from Empirical SCOTUS (pdf) provide a snapshot of the term and how it compares to years past. Quartz charted the stats on everything from narrowly decided cases to long drawn out opinions, prolific writers to enthusiastic questioners, which justices most often agree with each other, and also those least inclined to see eye to eye.

Close calls

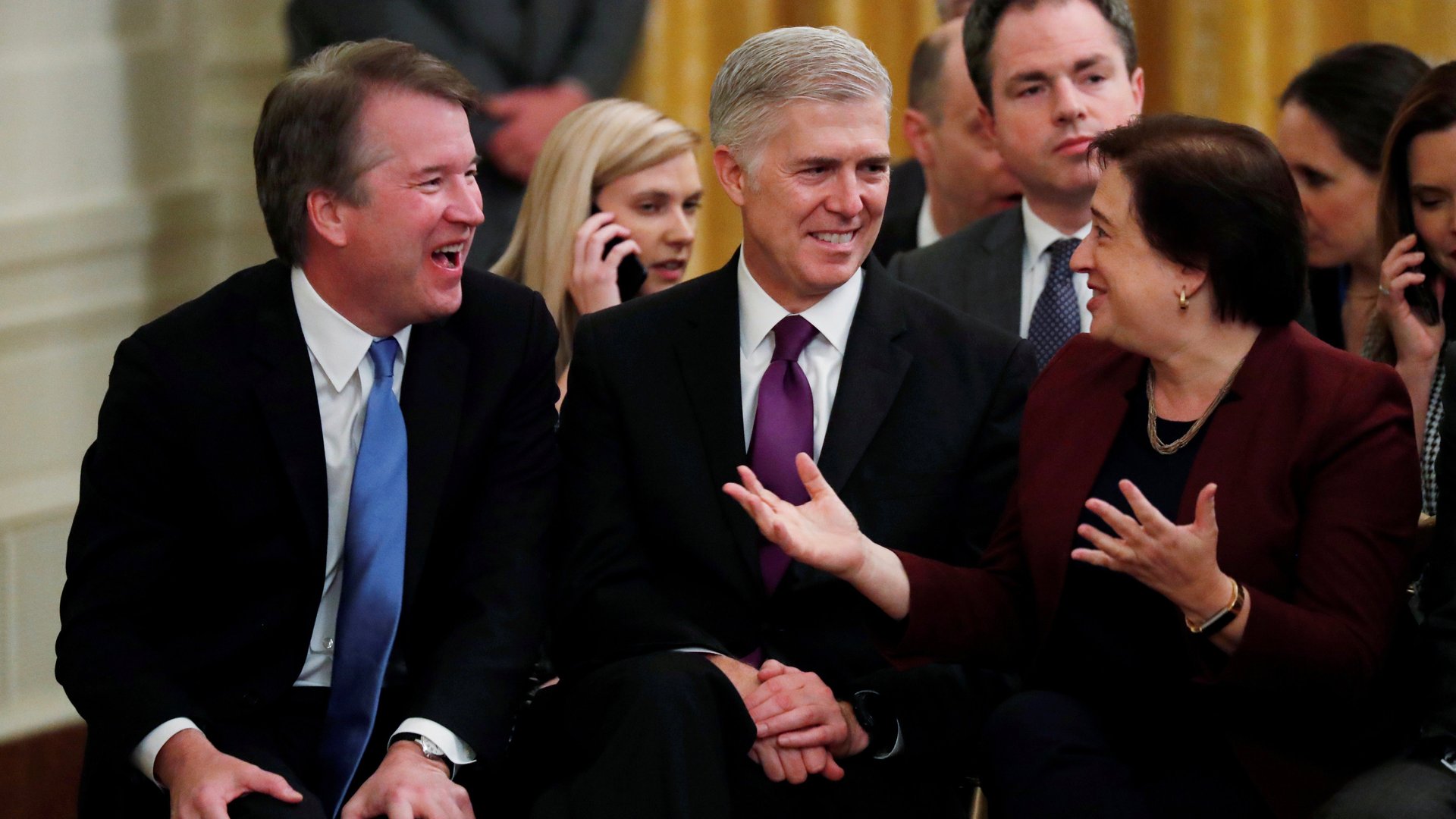

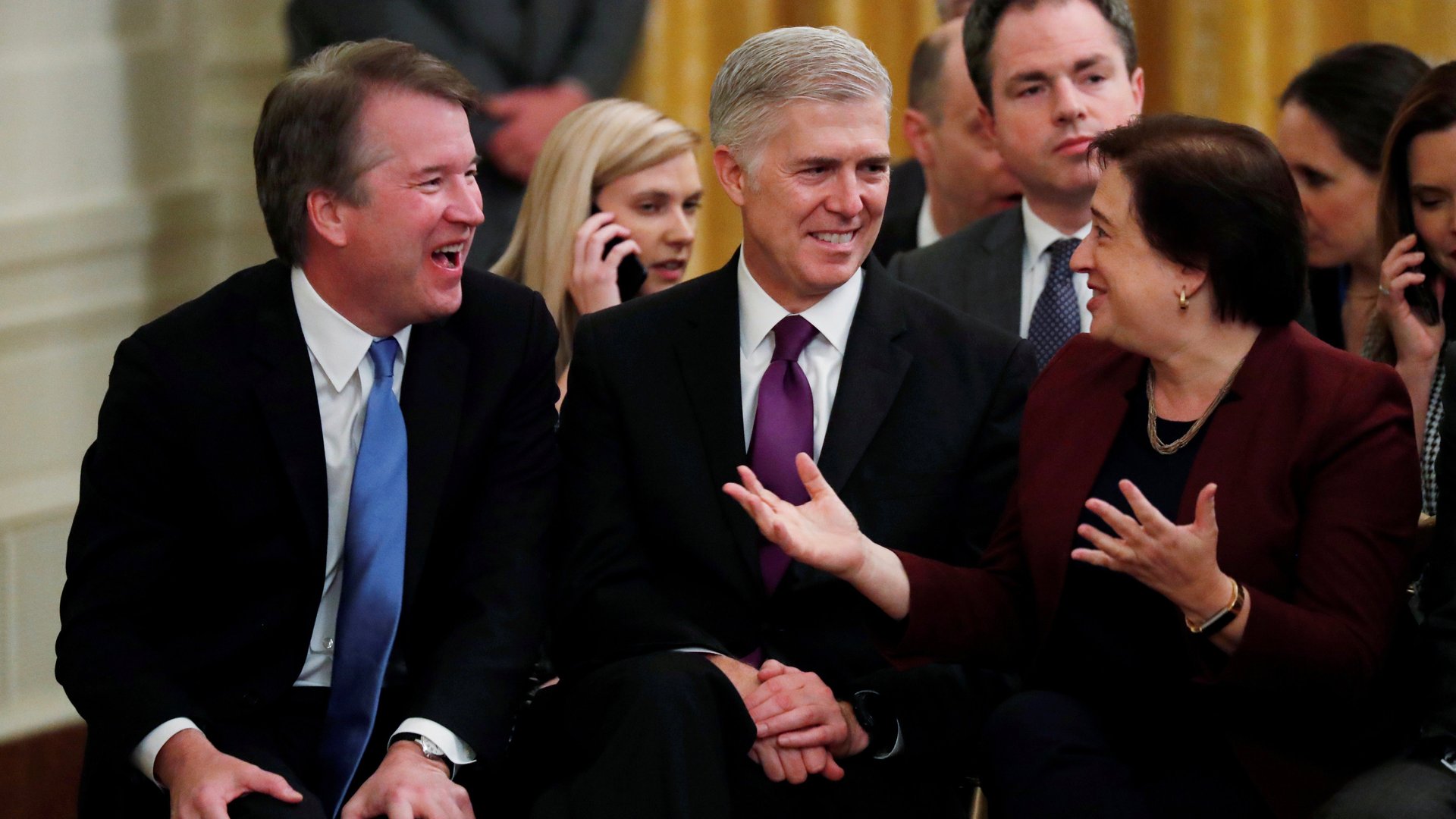

Of the 72 cases this term, 20 were narrowly decided in 5-4 decisions. Notably, the court’s conservative majority didn’t vote together for most of those cases. The conservatives on the bench are chief justice John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh. They agreed with each other on only eight of those 20 matters.

Meanwhile, the minority of liberals—Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor—won just as often as their colleagues on the ideological right. That’s because one conservative justice agreed with them on eight other close cases. And in the four remaining 5-4 decisions, the justices did not vote along expected ideological lines.

What’s most surprising about the liberal victories in these close cases is who among the conservatives emerged as their consistent ally. While one conservative justice each joined the liberals in four different narrowly decided matters, Gorsuch sided with the liberal wing four times, or in 20% of close cases. Without him, liberals would have won only half as many of these disputed decisions.

A look at the court’s closest cases since 2005 revealed that there aren’t usually so many 5-4 splits. That said, there have been a few sessions with a bunch of narrowly decided cases before. In 2006, for instance, there were 24 close calls.

What is striking about the most recent season is that there were 10 different alignments among justices in 20 contested cases, which is far more than seen previously. In 2006, for example, there were only six different alignments for 24 close cases. This indicates that the current bench is quite flexible and that ideology isn’t a perfect predictor of outcomes with the current nine justices.

Looking back at the 5-4 cases and ideological divides between 2006 and 2018 shows that liberals actually fared relatively well this term. In 2017, for example, 75% of 5-4 decisions were split along ideological lines and conservatives were victorious in 75% of those close cases. This term, 80% of close cases were decided along ideological lines and the liberals won half of them. If that still sounds like too much division, just consider that in 2015, all of the 5-4 decisions were split on ideological grounds and liberals won only 25% of the time (although it should also be noted that there were far fewer close cases that year than in 2018).

On the whole, the current crop of justices tend to agree with each other, though some are more inclined to join the crowd than others. Kavanaugh voted with the majority the most, in 91% of cases. Roberts was in the majority in 85% of cases. Yet even those most often in the minority—Ginsburg, Thomas, Sotomayor, and Gorsuch—voted with the majority 75% of the time.

Opinionated

The justices don’t all write opinions for each case. The majority opinion is assigned by the most senior justice in the majority on any given case, which is Roberts, the chief justice, whenever he’s in agreement with most of the other justices. When Roberts is in the minority, however, seniority is determined by years on the high court.

The chart below shows how many total opinions each justice wrote and whether it was the majority opinion, a concurrence, or a dissent. The chief justice wrote 12 opinions total, seven for the majority, two concurrences, and three dissents. Only Kagan wrote as few opinions as Roberts. Thomas wrote the most by far, authoring eight majority opinions, 14 concurrences, and six dissents. Breyer and Gorsuch were the term’s most frequent dissenters, writing 10 dissents each.

The high court imposes strict word limits on lawyers filing briefs. But the justices themselves aren’t always so concise. Empirical SCOTUS deemed opinions of five pages or more “long.”

Thomas, it turns out, writes lengthly opinions, 19 out of 28 in total. Gorsuch is also wordy, penning 19 long opinions out of 23. Breyer seems most inclined to make a short story long, however. He wrote 20 opinions, 18 of which ran five pages or longer. Similarly, Kagan wrote only 12 opinions but 11 of them were long.

Agree to disagree

Some people on the court tend to agree with each other more than others. This chart shows which justices agree the most and at what rate. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Kavanaugh, the most junior justice, agrees an awful lot with his boss, Roberts, at an overall rate of 93.8%. But Ginsburg and Sotomayor also often see eye to eye, agreeing at a rate of 93.1%. Kagan agrees with Ginsburg and Sotomayor in 87.5% of cases.

There are also justices who regularly disagree with each other. Still, even the most commonly opposed—like Ginsburg and Thomas, or Sotomayor and Thomas—agree with each other half the time. Interestingly, Gorsuch and Ginsburg have sniped at each other in opinions but actually agree relatively frequently, in 62.5% of cases, whereas Breyer and Gorsuch only agree 54.2% of the time.

Curiosity and questions

Court dynamics are revealed in all aspects of the job and oral argument is no exception. The next chart shows which justice most frequently asks the first question at these sessions. Ginsburg doesn’t ask the most questions of advocates overall, but she is most inclined to start the questioning. Meanwhile, Thomas, who wishes justices would just let lawyers speak during arguments, never begins the questioning and has very rarely ever asked a question.

Also telling is the frequency with which a justice asks questions during argument sessions. Sotomayor was extremely curious, posing an average of more than 23 questions per argument, while Thomas spoke not at all. Roberts, Alito, Kagan, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh asked on average about 15 questions per session.

Now, all that’s left to do is enjoy the summer while the justices are on break and wait for them to return to work in the fall.