Six weeks after the Brazilian politician Manuela d’Ávila gave birth, a stranger approached and started hitting the sling cradling her child. “Did you buy this in Miami?,” the woman asked d’Ávila, who in a few short years would go on to lose the 2018 bid to be Brazil’s vice president. The question parroted disinformation, spread around Brazil, that d’Ávila had splurged on baby products abroad.

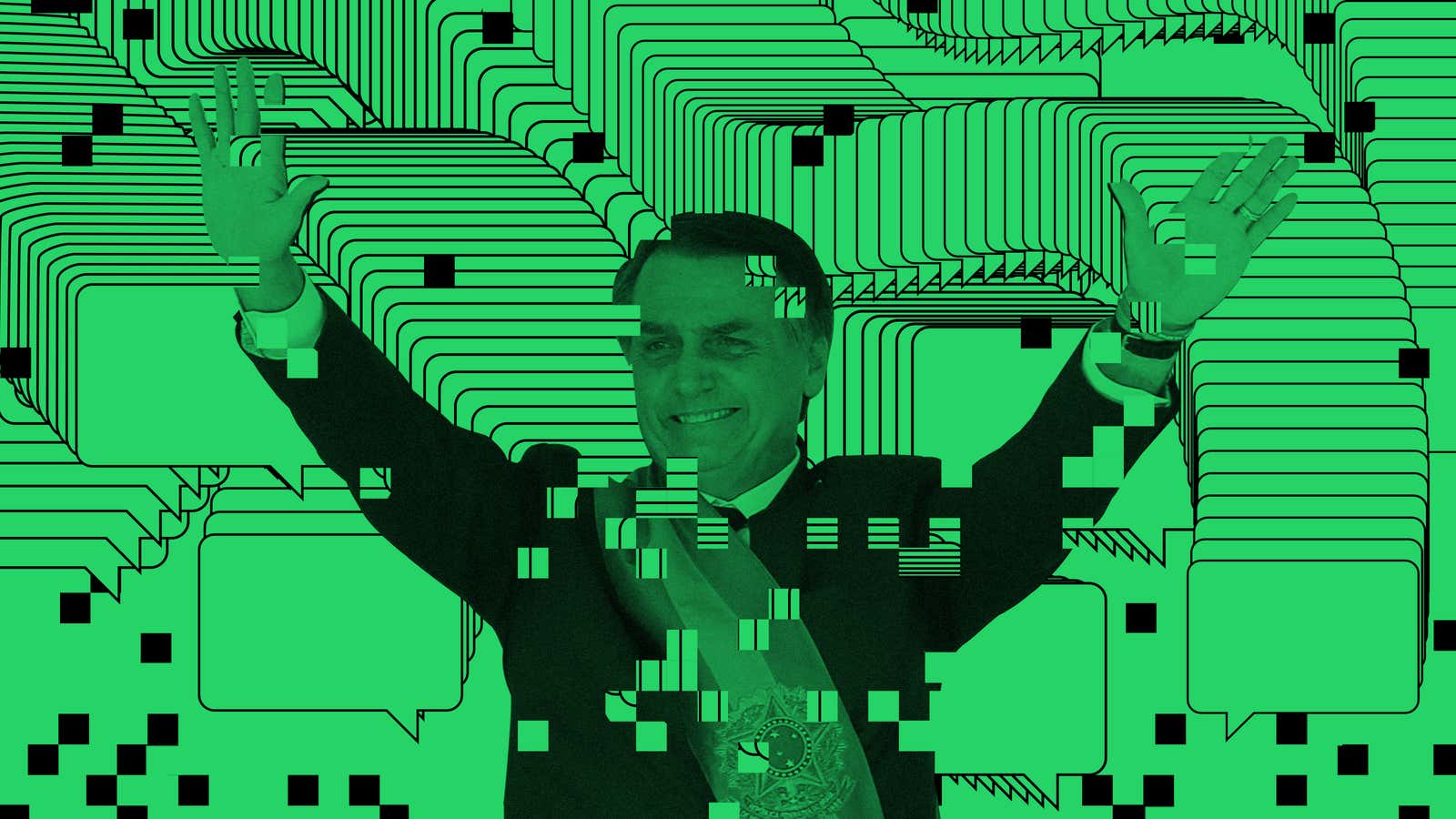

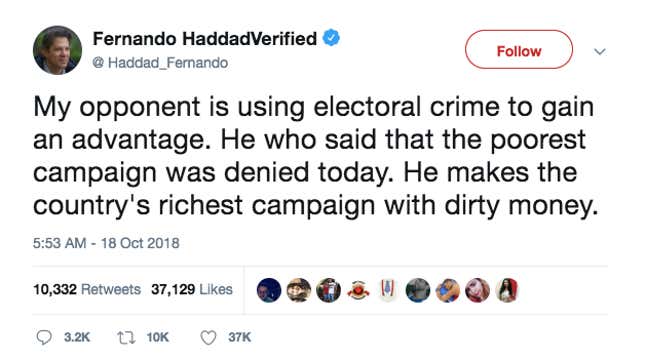

Taken alone, this lie may seem bizarre and innocuous. Yet last year, during the 2018 presidential election that swept far-right demagogue Jair Bolsonaro to power, falsehoods like this one built into a crescendo that distorted political conversations beyond any semblance of reality. Millions saw messages falsely claiming d’Ávila said Jesus was transgender, that her Worker’s Party (PT) running mate Fernando Haddad gave children bottles with penis-shaped teats to reduce homophobia, and that Haddad said children should be property of the state at age five. WhatsApp is the most popular messaging service in Brazil, with 120 million users, but these political lies did not ping through the country organically.

Cambridge Analytica used data to target political adverts via Facebook in the 2016 US presidential election. In Brazil, WhatsApp was the medium of choice, with pro-Bolsonaro companies buying datasets of phone numbers to blast WhatsApp users with anti-Haddad messages, according to a report by one of Brazil’s biggest newspapers, Folha de São Paulo. Such fake news campaigns are “poisonous bombs that enter the networks with a lot of strength,” Paulo Teixeira, PT leader in the lower house of Parliament, told Quartz, speaking in Portuguese.

Fake news spread via WhatsApp is even more difficult to combat than the Facebook version of this phenomenon. The messaging app, owned by Facebook, allows groups of up to 256 people and lets users forward messages five times, which means messages can be quickly transmitted to thousands of people. Unlike Facebook or Twitter, it’s a closed medium with end-to-end encryption, and so lies can’t be easily monitored or checked. This combination of privacy and mass broadcasting make it “the perfect medium for these disinformation campaigns,” said Pablo Ortellado, professor of public policy management at Universidade de São Paulo.

In Brazil, it’s illegal for political campaigns to buy databases and target people without their consent, and politicians are banned from using bots to blast out messages in bulk. President Bolsonaro, known as the “Trump of the Tropics” and notorious for his incendiary remarks, denies that he and his allies relied on illegal harvesting of data to spread their message, and says those who paid for the WhatsApp campaigns did not do so at Bolsonaro’s behest. It’s theoretically possible that the multi-million dollar WhatsApp campaigns were arranged by supportive businesses, but undeclared corporate donations are prohibited in Brazil. And so, even if the president is not culpable, the orchestrated WhatsApp messages raise serious legal concerns for Brazil’s 2018 election.

Since Bolsonaro came to power, misuse of WhatsApp has infiltrated elections around the world, from India to Spain, and its influence shows no signs of fading. Even the US, where WhatsApp is less commonly used, is vulnerable to this distortion in the 2020 presidential elections. “The Hispanic population uses WhatsApp,” Patrícia Campos Mello, the Folha journalist who uncovered the illegal use of data and bots in Brazil’s election, told Quartz. Let’s say politicians want to target first-generation Cuban Americans who resent illegal immigrants entering the country, she added: “You can just microtarget.” The world is still struggling to grasp the impact of Facebook disinformation and microtargeting in elections, yet Bolsonaro’s victory shows we face the same threat of subversion from an even more impenetrable forum.

The power of WhatsApp

A few months before the presidential election, WhatsApp effectively brought Brazil to its knees. Truckers across the country went on strike and blocked roads in a so-called “paralyzation” to protest the rising costs of diesel. “I wanted to shut down the country,” one of the key figures behind the protests, Wanderlei Alves (known as Dedéco) told Quartz. He and his colleagues created around 500 WhatsApp groups of tens of thousands of truckers in the first three months of 2018, he said, and used this forum to share updates and schedule strikes. At the peak of organizing, Dedéco said he received 50,000 messages every three hours.

With such examples of WhatsApp’s political might, Brazil’s political campaigners could not afford to ignore the app.

No one denies that Bolsonaro’s campaign used Whatsapp and social media to their political advantage. “Without the internet, Jair Bolsonaro would never be the president,” congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, Jair Bolsonaro’s son, told Quartz. Most telecoms companies offer WhatsApp for free in Brazil, and the app has become the go-to method for hearing from political candidates, talking with friends, and reading the news. Limits on TV and radio time for presidential candidates in the election only heightened WhatsApp’s importance last year.

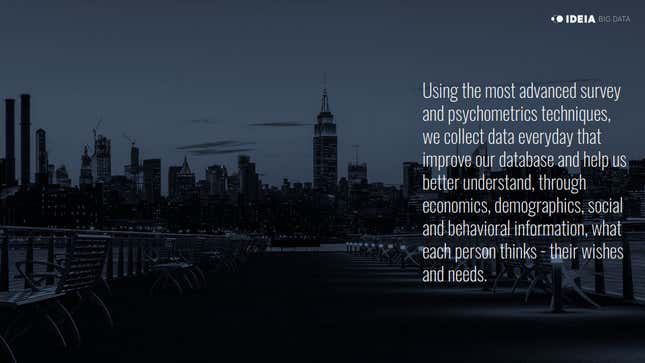

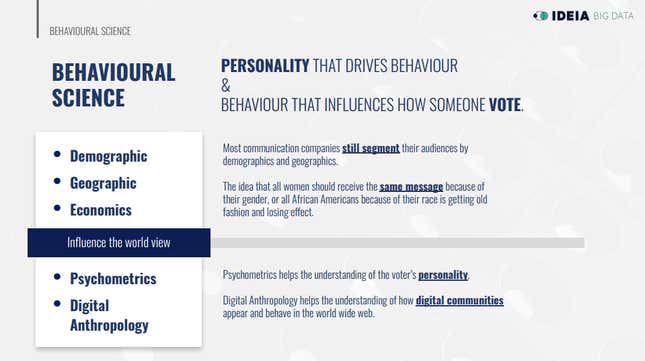

Brazil’s WhatsApp political conversations were further amped up by digital marketing companies, including those that use data to target messages to voters.

This targeting is not only based on standard demographics—like age and gender—but more advanced profiles of everything from how social you are to whether you tend to put others’ needs ahead of your own. Moriael Paiva, digital vice-president at political marketing company IDEIA Big Data, told Quartz the company uses psychometric tests to profile people and send messages that appeal to specific personality types. IDEIA’s sales pitches to clients boldly advertise these tactics:

Detailed political targeting is legal in Brazil if parties only use data that they’ve collected themselves, from voters who consent to being messaged. But misuse of data turned WhatsApp political propaganda into an overwhelming onslaught. Several marketing agencies had contracts worth up to R$13million (around $3.4 million) to send hundreds of millions of anti-Haddad messages, according to a report from Folha published the month of the election. These contracts explicitly gave one pricing option for messages targeted to those in the political party’s database, and another price for sending the messages to third-party databases. Not only is it illegal in Brazil to send messages on behalf of a political party to non-party databases, but funding mass messaging in support of one candidate is considered a campaign donation. Undeclared corporate donations are prohibited, making the WhatsApp messages even more illicit.

There’s also evidence of identity threat: Several companies bought the personal data of tens and thousands of elderly people to falsely register SIM cards in their names, according to a December 2018 Folha report, and used the SIMs to send mass political messages. Brazil is home to frequent data leaks and a large data black market, making it easy to misuse data. In São Paulo, there’s even a data black market neighborhood, Santa Efigênia, where leaked data and SIM cards are sold under fake identities. And so, though WhatsApp banned accounts sending bulk political messages during the 2018 political campaign, the ready availability of black market data and SIM cards make it easy to simply create new accounts. WhatsApp banned several accounts linked to the companies sending bulk political messages following the Folha report. So far, the companies involved have denied or failed to respond to accusations.

Misuse of data was a standard feature of political campaigns in 2018. Loester Carlos Gomes de Souza (better known by his nickname Loester Trutis), one of the right-wing politicians that swept into office on a wave of Bolsonaro support, said he was approached by marketing firms who offered to help with microtargeting. “It goes like this: ‘Whom do you want to us to fire off [messages] to? Industrial farmers?’” he said, mimicking the companies’ offers. Though these firms didn’t explicitly volunteer to share data sets in their pitches, and Trutis said he turned them down, he believes left-wing politicians made use of such illegal services.

Microtargeting became so precise during the election that some Bolsonaro supporters were labelled “gay kit,” and bombarded with homophobic WhatsApp messages, reported the Intercept, while others were sent “weapons” or “church”-related messages, depending on their interests. The software then monitored whether recipients responded positively, negatively, or neutrally, and adjusted future messages in response.

Alessandro Molon, congressman from the left-wing Brazilian Socialist Party and leader of the opposition in the House of Representatives, said he was also approached by such marketing firms. Though most people will ignore a message from a stranger with a seemingly unbelievable piece of gossip, Molon said, there will always be some who are incredulous and amazed enough to pass it on. “You take one of these messages and you forward it to your groups,” he added. “So it’s not as if the bots reach everyone, necessarily. But directly, or indirectly, they do.”

Certainly some of the fake news sent via WhatsApp during the election came from Bolsonaro supporters who weren’t involved in a coordinated campaign. But the massive volume—together with the Folha reports and evidence from BBC Brazil that political campaigns scraped phone numbers off Facebook—implies that some activity was professionally orchestrated. Brazilians who hadn’t given their data to political parties were frequently added to political WhatsApp groups by strangers in 2018, suggesting their data was bought by companies sending out mass messages.

Bolsonaro and his team deny that they knew of or helped orchestrate any of the anti-Haddad campaigns. “I had millions of messages in favor of my campaign, and maybe a few millions against, too,” president Bolsonaro said in June. Indeed, there’s evidence that Haddad’s PT party also worked with mass-messaging companies (though the party could have done so using its own data), and several other leftwing politicians, including Molon, said they believe individuals on the left used the same tools as pro-Bolsonaro corporations. Brazil’s right wing, though, dominated the WhatsApp conversation.

WhatsApp campaigns favor a certain kind of politician

The political left in Brazil, grounded in traditions of proper political practice, wasn’t quick enough to throw off its old ways and embrace online standards. At least, that’s what some politicians believe: “We use the same tools, we use robotics and social networks… But with less efficiency than the right wing politicians,” said Margarida Salomão, PT congresswoman. “The right wing is a different kind of politician. They’re YouTubers,” she added. Alexandre Frota, a former porn star and newly-elected member of Bolsonaro’s party, is one of those YouTubers.

Frota used his platform to weigh in on the reports of illegal pro-Bolsonaro WhatsApp messages. After Folha journalist Campos Mello published evidence of the coordinated campaigns, she became the target of fake news herself. Thousands of memes and lies were circulated; dozens of people found her phone number and called her, telling her to leave the country if she cared for the safety of her son; photos of her house were posted online. The antagonism was so intense that Campos Mello had to hire a bodyguard for 15 days. “It’s weird, I never had any security, and I go off to Syria and places like that,” she said.

In the midst of this volatile conversation, Frota created a YouTube video in which he called the journalist a “vagabunda.” The word, which literally translates as “vagabond,” is used as an insult in Brazil to imply that a woman is a whore. Campos Mello said her seven-year-old son found the YouTube video two months ago, and asked his mother if they could watch it together.

Frota, when challenged, admitted he shouldn’t have made the video. “I acknowledge my mistakes,” he said, when I met him in Brasilia in June, three days after talking with Campos Mello. Specifically, he shouldn’t have called Campos Mello a whore, he said. Yet Frota, like everyone I spoke with from Bolsonaro’s party, dismissed Folha’s evidence as false. The politician is broadly proud of his social media presence, and said he attracts a large following online because he is “aggressive” on social media. When an aid suggested he means “incisive,” Frota insisted otherwise: He is “aggressive.”

The outspoken politician, whose short-sleeved monogrammed shirt exposes some of his 47 tattoos, is unavoidably reminiscent of the Incredible Hulk, with muscles threatening to burst through his seams. He has 164,000 followers on Instagram, and believes he attracts both attention and support because he says what others think, but are too afraid to say. Frota is part of a generation of far-right politicians who, like president Bolsonaro himself, rode to political success on the back of YouTube videos, tweets, and WhatsApp conversations. Their affinity for social media explains, in part, why Bolsonaro’s team recognized WhatsApp’s potential and were so far ahead in taking advantage of it.

Politicians such as Frota and Trutis first came to politics as activists and outsiders, buoyed by social media supporters. Trutis, who succinctly described his politics as, “pro-life, pro-gun, pro-God,” acknowledged he won thanks to WhatsApp. His administrators belonged to 600 WhatsApp groups, some of which they created and some of which were started by supporters, and used the app to channel enthusiasm, even in areas Trutis never visited. His team worked with especially vocal fans as “influencers” to help galvanize others.

Plenty of the social media-friendly right-wing politicians revel in audacity—like calling a journalist a “vagabond”—that would be condemned in Congress debates and primly reported in the press, but are shocking enough to zip around WhatsApp conversations. Though Bolsonaro himself has a long career in politics, he portrays himself as an outsider and has plenty of examples of outrageous remarks: The gun-loving politician once told a female representative in Congress she was “too ugly to rape,” said he’d rather his son was dead than gay, that the descendants of slaves aren’t “even good for procreation any more,” and that he’s “in favor of torture.”

WhatsApp is the natural home for demagogue politicians. And the “aggressive” social media style of Frota et al seems likely to attract the same supporters who are drawn to extreme fake news. Stories about baby’s bottles shaped like penises are ridiculous but also funny, engaging, and too-crazy-not-to-talk-about. They’re a natural fit for the larger-than-life right-wing politicians.

Many left-wing politicians I met with seemed muted and dull in comparison. Congressman Teixeira’s office was in a disarray of folders and files and stapled packets when we met, his two calendars still set to May (though we met in June), and a pile of dirty Tupperware on his desk. The mess has no bearing on his work as a politician: A series of index cards on the wall showcased his various bills’ progress through the legal system, and he said he’s put forward more successful laws than any other congressman since 2010. It’s hard to imagine him, though, provoking more WhatsApp conversation than Frota.

Similarly, PT congressman Orlando Silva, who led a recent bill for more privacy protections, sat hunched and still, and spoke carefully in response to questions. Silva, who has faced corruption accusations himself (he resigned as sports minister in 2011 following claims, which he denied, that he helped arrange millions of dollars of kickbacks ahead of the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics), talked in a low, concerned voice about “the advent of post-truth, where narratives are constructed.” Silva created a bill that mimics much of Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and believes this will help prevent political misuse of data. Ultimately, though, he thinks the culture of data abuse will only fade if the public is aware of the impact and demands change.

Both Silva and Salomão emphasized that abuse of data increased the problem of fake news on an exponential scale. “Fake news is not a new thing. Lies in politics is a normal thing,” said Salomão. “Nowadays it’s worse because you have robotics doing this ugly work.” Or, in Silva’s words: Fake news went from “artisanal production to an industrial scale.”

What good is the law?

Brazil’s Supreme Court judge Marco Aurélio Mello has noble ideas about how the law should respond when politicians misuse data. “They should act objectively regardless of whether the candidate they’re investigating won or lost the election,” he told Quartz. But Mello, who has gently creased eyes and a perpetual slight smile, making him the picture of benevolence, recognizes that this ideal doesn’t always uphold. When asked whether what should happen always does happen, he raised a hand and nodded, smiling. “I have to admit that it is possible that sometimes judicial powers don’t have the stomach to go against a powerful political figure,” he said.

These words validate the many who protest that Brazil’s courts have not responded effectively to political misuse of data. Brazil’s electoral court opened an investigation into political WhatsApp messaging following Folha’s reports but, eight months on, no one has been called to testify. Meanwhile, Peterson Rosa Querino, head of Quickmobile, one of the companies accused out sending out mass messages, was excluded from the lawsuit because the court said it could not find his address to notify him of developments. (Quickmobile did not respond to Quartz requests for comment.)

The investigation is moving “in very slow steps, if it’s moving at all,” said Molon, the socialist party leader of the opposition. Were the electoral court to prove major abuse of pro-Bolsonaro messages, it could revoke the 2018 presidential election result. And so, it’s widely believed that there’s trepidation to go against the president and be seen as sabotaging the leader. “If the elected official starts to face great difficulties in terms of popularity, that creates a more favorable situation for the advancement of an investigation,” added Molon.

Mello, who asked not to be photographed at his desk as he thought it made him look too pompous, is the rare Supreme Court member who’s been willing to go against his colleagues. As well as acknowledging the reluctance of the Electoral Court to topple Bolsonaro, he criticized a Supreme Court investigation into fake news, led by Justice Dias Toffoli. One branch of this investigation was dedicated solely to fake news about the Supreme Court, and demanded that Crusoé magazine retract an article that claimed Toffoli was engaged in corrupt dealings. The Court labelled this article “fake news” and threatened the publication with a R$100,000 (US $25,900) fine, before rescinding the order when presented with documents in support of the reporting.

“Not even at the time of the state of exception, which was the military regime, did we have a similar act,” Mello told Quartz. “It was a bad thing, in my view. It comprised a very outdated vision.”

Other members of the judicial system do not recognize a problem. Joel Souza Pinto Sampaio, chief advisor for international affairs at the Supreme Court, and Adão Paulo Martins de Oliveira chief communication advisor at the Supreme Court, seem utterly unperturbed by the Supreme Courts activity. “It’s not meant to censor anyone,” said Sampaio. “We’re in a democracy, it’s fair game to criticize and have free flow of opinions.”

He wore an ill-fitting suit and praised the virtues of Brazil’s judiciary with a consistently downcast manner. “Every candidate is held accountable at the electoral court for any possible wrongdoing,” he said. “No political pressure is necessary.”

Politicians can abuse data once they’re in power

Using the law to keep data abuse in check is not easy. Many of the platforms where disinformation is spread are international, and therefore slippery to pin down to national law. Though Facebook created a “war room” to scroll for fake news during the Brazil election, Campos Mello said the company has no permanent WhatsApp representative based in Brazil, and so referred her reporting queries to a PR account manager at Ogilvy advertising company. WhatsApp did not directly respond to queries about whether the company has a permanent representative employed in Brazil. A US spokesperson for WhatsApp said, “I’m not sure what permanently based in Brazil means—but yes, we had, and do have people representing WhatsApp in certain capacities that live in Brazil.” He did not respond to questions about whether those “representing WhatsApp in certain capacities” were WhatsApp employees or outside consultants.

But failure to address offenses only opens the door to more criminal activity. And politicians who would misuse data to get into office are unlikely to respect citizens’ privacy once in power.

Since taking office, Bolsonaro’s right-wing party has turned to data in its fight against students, whom it perceives as bastions of cultural marxism. In May, after hundreds of thousands of students protested government plans to cut university funding, the Minister of Education demanded that INEP (the government agency in charge of the national educational census), hand over all their data on students, from kindergarten to university.

The data is intensely personal—students’ address, their parents’ income, what they’re studying, their race—and several politicians told Quartz they were afraid it could be used to identify and target both Bolsonaro supporters and protestors. Though the Minister of Education eventually retracted the request under public pressure, an INEP employee (who asked not to be named for fear of retribution) said the government made it clear internally that they would eventually access the data.

Given the history of data abuse associated with Bolsonaro’s party, he’s worried about how this information could be used. “The election was not clean. There was a lot of misuse of information and data during the election,” he said. “We see the damage the misuse of data can cause and you’re talking about data of children.”

Abuse of data in an election, whether by politicians or corporations, can effectively undermine democracy. Once a politician comes to power, the potential implications are even more troubling. For a government with access to endless information, data can be a tool of dictatorship.