Apps designed to help people lose weight, track pregnancy, and have better sex are sharing personal information with third parties, often without making such practices clear to users. Quartz used an intercept tool to test several popular wellness apps and found users’ length of pregnancy and BMI bracket shared with Facebook, Google, and digital marketing agencies. Meanwhile, a sex app quietly shared users’ location data. Some of these apps’ privacy policies were difficult to locate or misleading. The information Quartz found apps sharing with third parties includes:

Pregnancy data

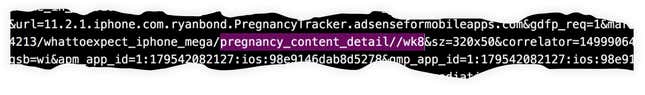

“What to Expect” pregnancy app told Google’s advertising network that a user was eight weeks pregnant seconds after that information was entered into the app. Users can only find the app’s long and jargon-heavy privacy policy if they seek it out, low down in the app’s settings menu. What to Expect did not respond to requests for comment.

Workout data

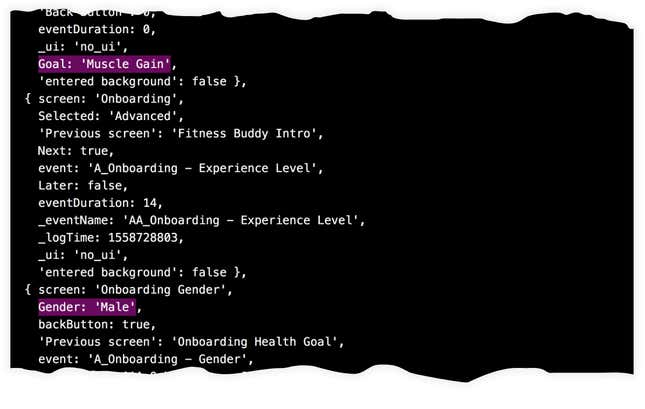

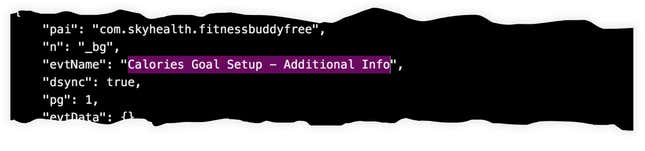

A fitness app, Fitness Buddy, sent Facebook a user’s gender, fitness goal, phone battery and memory level, time zone, and cell phone carrier. In addition, the app told the domain Wzrkt.com similar phone details and that the user had set a calorie goal. A security researcher previously revealed this domain belongs to engagement platform CleverTap, which allows marketers to identify and engage users. Fitness Buddy also had a difficult-to-locate privacy policy filled with unclear sentences such as, “We may receive Personal and/or Anonymous Data about you from companies that provide our Applications by way of a co-branded or private-labeled website or companies that advertise their products and/or services through our Applications.” Fitness Buddy did not respond to requests for comment.

Location tracking on a sex app

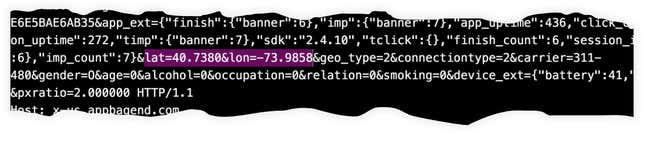

Other apps had clearer and easier-to-find privacy policies, but harvested more personal data. Desire, a sex app couples use to send their partners sex dares—which sometimes include illegal activity such as having sex in public places—keeps track of user location. The app sent latitude and longitude coordinates of its users to appbaqend.com. The top of this page is headed “Appodeal”, which is an ad monetization company, suggesting the two are connected. The app also communicated with Amazon and Google. It’s not clear why the app would need location data to function. In response, Desire said the app is GDPR compliant, and users need to accept the privacy policy to register.

BMI data

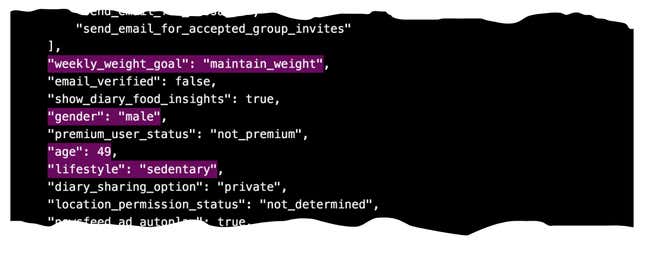

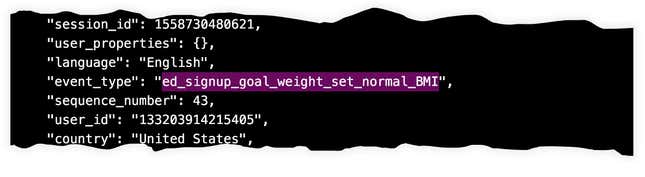

Popular fitness app MyFitnessPal sent a user’s gender, age, weekly weight goal, lifestyle (“sedentary”), and BMI bracket (“normal_BMI”) to analytics software company Amplitude.com, along with the date on which a user set a weight goal, the make of their iphone, their language, and the name of the cell phone carrier. Amplitude describes itself as collecting data to analyze user behavior. “It goes beyond basic metrics like daily active users or pageviews, revealing how engagement with different features can lead to retention, conversion, and revenue,” reads its website. In response, Under Armour, which owns MyFitnessPal, said it uses Amplitude to evaluate user activity for internal purposes. “Under Armour is committed to end user privacy and ensuring transparency of our data collection and use practices,” said a spokesperson. The company did not explain how phone make and carrier inform their understanding of how the app is used.

Quartz identified the information shared by using a technique called “man in the middle,” in which an intercept tool decrypts encrypted messages en route from the phone to their intended destination. Such widespread sharing of data is not unusual. As Quartz reported in Monday’s guide to Big Data, a 2015 study of apps in Australia, Brazil, Germany, and the US found that 85% to 95% of free apps and 60% of paid apps share personal data with third parties. A study of 26 depression and smoking cessation apps earlier this year found 29 transmit data to Facebook or Google, while the Wall Street Journal found a menstruation-tracking app was sharing ovulation dates with Facebook.

Apps are a “digital trojan horse,” said Jeffrey Chester, Executive Director of the Center for Digital Democracy. Many apps are explicitly designed to encourage users to enter personal data, which they then share with third parties. Although all of the data Quartz spotted apps sharing was pseudonymized, it’s difficult to guarantee that information is truly anonymous; the data industry is adept at “identity resolution,” whereby pseudonymised data is matched to specific individuals.

“It’s currently excruciatingly difficult to control what apps share with others,” Frederike Kaltheuner, head of corporate exploitation at Privacy International, wrote in an email to Quartz. She added that third parties whose code is embedded in apps could combine data they receive with additional data from other sources, and so create detailed profiles.

Johnny Ryan, chief policy officer at Brave, a web browser that blocks ads and website trackers, added that data is considered “personal” under Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) if it can be used, alone or combined with other data, to identify someone. Location information and habits are generally personal data, he wrote in an email to Quartz, and combinations of information about a device and use of an app can be personal. “This is a broad definition, much broader than the definition of “personally identifiable information,” he wrote, “and it means that these apps should be very careful about what they do with the data.”

Ultimately, there are so many free apps because selling data is an increasingly common business model. But unless customers use man-in-the-middle to spy on their own apps, there’s no way to know for sure exactly what information is being shared.