Brazil’s far-right leadership is very much a family affair. President Jair Bolsonaro, known as the “Trump of the Tropics,” relies on his sons—Eduardo, Carlos, and Flávio—as his closest advisors. Other politicians despair at the dynastic state of affairs. “I’m despondent that crucial decisions about Brazil are being made between spaghetti and dessert on a Sunday night,” Brazil’s Worker’s Party congressman Orlando Silva told Quartz.

So far, there’s no infiltrating the Bolsonaro ranks. On Friday (July 12), President Bolsonaro announced he’s inviting his son Eduardo to be ambassador to the United States, and Eduardo told reporters he plans to accept the nomination.

Eduardo Bolsonaro has a strong affinity for the US and President Trump in particular. His effusive personal enthusiasm will likely to go down well with Trump, who recently declared he would never work with UK ambassador Sir Kim Darroch after leaked cables showed the UK ambassador said Trump “radiates insecurity” and will never “look competent.” Brazil’s ambassador nomination suggests President Bolsonaro hopes to use his son to get closer to the US.

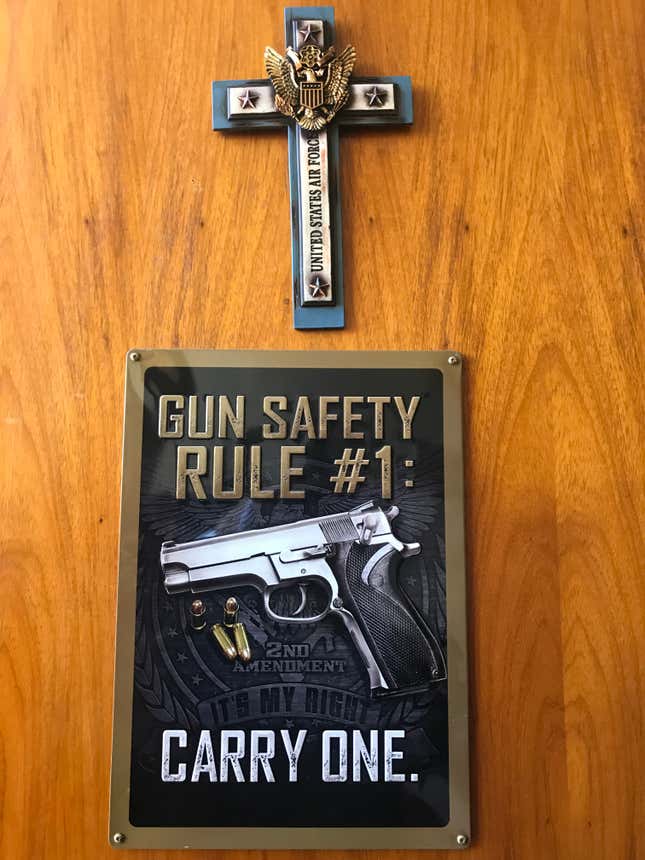

Eduardo Bolsonaro’s affection was on display when Quartz visited his office in Brasilia’s National Congress in June. The room is decorated with a copy of the US constitution (but no constitution of Brazil); plastic figurines of Donald Trump carrying a gun, George Washington, and Ronald Reagan; a pen topped with an automated plastic Donald Trump that punched the air and said “don’t touch the hair” at the touch of a button; and a plaque of the second amendment, alongside other gun paraphernalia. Other international influences include an Israeli flag and a mug decorated with Margaret Thatcher’s face.

The president’s son wasn’t in his office when Quartz visited, but two assistants were there to show off Eduardo Bolsonaro’s collection of kitsch. Two days later, while the congressman was attending a conference in Rio de Janeiro, we met for an interview in which he further demonstrated his ties with the US.

Bolsonaro is friends with Steve Bannon, and said the two have met three or four times in both Washington, DC and New York since 2017. Earlier this year, Bannon invited Bolsonaro to be the head of the South American branch of The Movement, an organization that promotes right-wing populist ideals. The main goal of The Movement, said Bolsonaro, is “to do the opposite of the socialists.”

He and Bannon want to work together to empower western culture. “We respect the women. You have other parts of the world where they didn’t grow up with this Jewish Christian mentality, so they don’t respect that much the women,” he added. His comment echoes Bannon’s view that the Judeo-Christian west is in a struggle against Islam; the former Trump advisor believes the United States is in a “global war” with “Islamic facism.” Yet despite Bolsonaro’s claims about respecting “the women,” there’s evidence of the opposite within his own family; his father once told a congresswoman she didn’t deserve to be raped by him.

The Movement also aims to champion free market economics, a goal that Bolsonaro generally supports—with some reservations. Brazil’s biggest trading partner is China, accounting for 26.8% of Brazil’s exports (more than double the 12.1% that goes to the US.) Yet the Bolsonaro clan doesn’t have nearly such warm relations with China as it does with the US.

Eduardo Bolsonaro said he worries that China’s financial investment could lead to political influence. “You don’t have the freedom to do whatever you want. If you do something China doesn’t like, they can take out all the investment, all the money they put in the country,” he said. Though he welcomes trade from China, Bolsonaro said he plans to protect certain areas, such as security intelligence, from international investment. “We want to keep our sovereignty,” he added.

He showed no similar skepticism towards his relationship with the Trump administration. Even before he was nominated as US ambassador, Bolsonaro embraced potential collaborations with the United States, suggesting Brazil could work alongside the US and Israel to create business opportunities in the Amazon rainforest. “We don’t think we’re going to do everything by ourselves in the Amazon,” he said.

Currently, a football-pitch-sized area of the Amazon is destroyed every minute under President Bolsonaro. His son said the goal is to protect the Amazon while developing eco-tourism. “To preserve is not to isolate. We have to integrate the Amazon with the rest of Brazil,” he said. To ignore the “mountain of opportunities” would be stupid, added the congressman: “If you take a look in the Amazon, maybe you have the cure for cancer or the cure for another sickness.”

Eduardo Bolsonaro is not US ambassador yet. The appointment must be approved by Brazil’s Senate foreign relations committee and then the full upper house before Eduardo can formally start the role. He’ll also have to renounce his current role as congressman, though that’s likely to be a worthwhile and calculated sacrifice for such an ardent Trump fan.

Much as Trump’s victory divided the United States, President Bolsonaro’s victory divided Brazil. Bolsonaro won with 55.7% of the vote, though polls suggest his popularity has since plummeted. Eduardo Bolsonaro is not worried. President Bolsonaro is surrounded by fans whenever he gets out of his car, he said.

Certainly the Bolsonaro family has devoted supporters. When Bolsonaro and I met in June, we stood in a corner and the congressman kept his face turned carefully towards the wall. Whenever someone caught a glimpse, they asked him for hugs and photos. “Some institutes are going to tell you that [President Bolsonaro’s popularity is dropping],” he said. “The same institutes said Jair Bolsonaro would never win the election or even go to the second round.”

This mistrust echoes President Trump’s claim that his own disappointing poll numbers are “fake.” The leaders of both Brazil and the United States have plenty of similarities: Both enjoy using social media to engage with the public, defy political correctness, and espouse nationalist sentiments. With such close ties to the US and respect for Trump’s values, President Bolsonaro’s son is well-placed to bridge the two right-wing governments.