If you work in computer science, or recently graduated from an elite university, or read Vox’s Future Perfect section, or find yourself drawn to certain “highly rational” corners of the internet, there’s a good chance you’ve already come across effective altruism.

Now more than a decade old, EA—as it has been known since 2011—is a philosophy, a social movement, and, increasingly, a way of life. And it’s thriving. EA started in 2007 with GiveWell, a rigorous charity assessment tool. In 2011, the Centre for Effective Altruism was formed in the UK to give the movement structure and direction. EA raises billions for recommended charities and causes, as well as through its own philanthropic funds.

Effective altruists congregate the world over with nearly 400 global chapters, often connected to high-ranking universities or tech centers. Their numbers encompass at least two Giving Pledge signees, including Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz, whose assets exceed $10 billion, as well as dozens of other high-profile donors. Arguably, no other secular movement ever has had as much impact in changing how people think about their philanthropic responsibility.

The movement’s simplest premises are hard to disagree with. Effective altruists wants to do good, and ideally the most good possible per dollar spent. To figure out the best way to do that, researchers uses rigorous analysis of data to work out which actions will affect the greatest number of lives in the most positive manner.

Historically, this has involved particular attention to humanitarian crises that don’t grab headlines, such as malaria and parasitic worms in the developing world. As the Centre for Effective Altruism’s website explains, these issues should be “great in scale, highly neglected, and highly solvable,” where additional resources have the potential to do a great deal of good. Many of EA’s proponents, including Australian moral philosopher Peter Singer, will tell you that if you have money to spare—and you probably do—you are doing something quite staggeringly wrong by not diverting some of it toward saving the lives of the world’s more vulnerable beings.

In the past 12 years, EA has gone far beyond simply informing people how to give effectively. Now, there’s an EA perspective on almost every different aspect of life: where you work, what you buy, even what you eat and how you travel. It has inspired people to give up kidneys or change their careers. It has even affected government policy. Many bright young people have been convinced by the instruction of “earn to give”—that is, to pick a high-salary career in order to redistribute their wealth, instead of choosing work in charity or other traditionally philanthropic sectors.

But things are changing. More and more, EA adherents believe the most effective way to support the movement is in preventing tomorrow’s problems before they happen—and especially those they think could lead to human extinction. What they believe these problems are, however, often runs contrary to mainstream thought.

Will MacAskill, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Oxford, is one of the movement’s co-founders, along with Australian philosopher Toby Ord. Now president of the Centre for Effective Altruism, MacAskill helped found the organization 80,000 Hours in 2011, which helps the altruistically-minded to choose careers with the largest positive social impact. In 2015, he published Doing Good Better, a much-read guide to the movement that was praised by Bill Gates and Freakonomics author Steven Levitt alike.

MacAskill, 32, is tow-haired and lanky, with the front-tooth gap the French call “les dents du bonheur”—the teeth of happiness—and a pronounced, trilling Scottish accent. (MacAskill wrote a series of articles for Quartz in 2015 and 2016 on some of the questions EA seeks to answer.) In June, I met with him in his office at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Practical Ethics, in a yellow-brick building on top of a glass-fronted, no-frills PureGym franchise.

In the four years since publishing his book, MacAskill said, the movement had changed in two important ways: its problems of interest, and how it thinks they should be addressed.

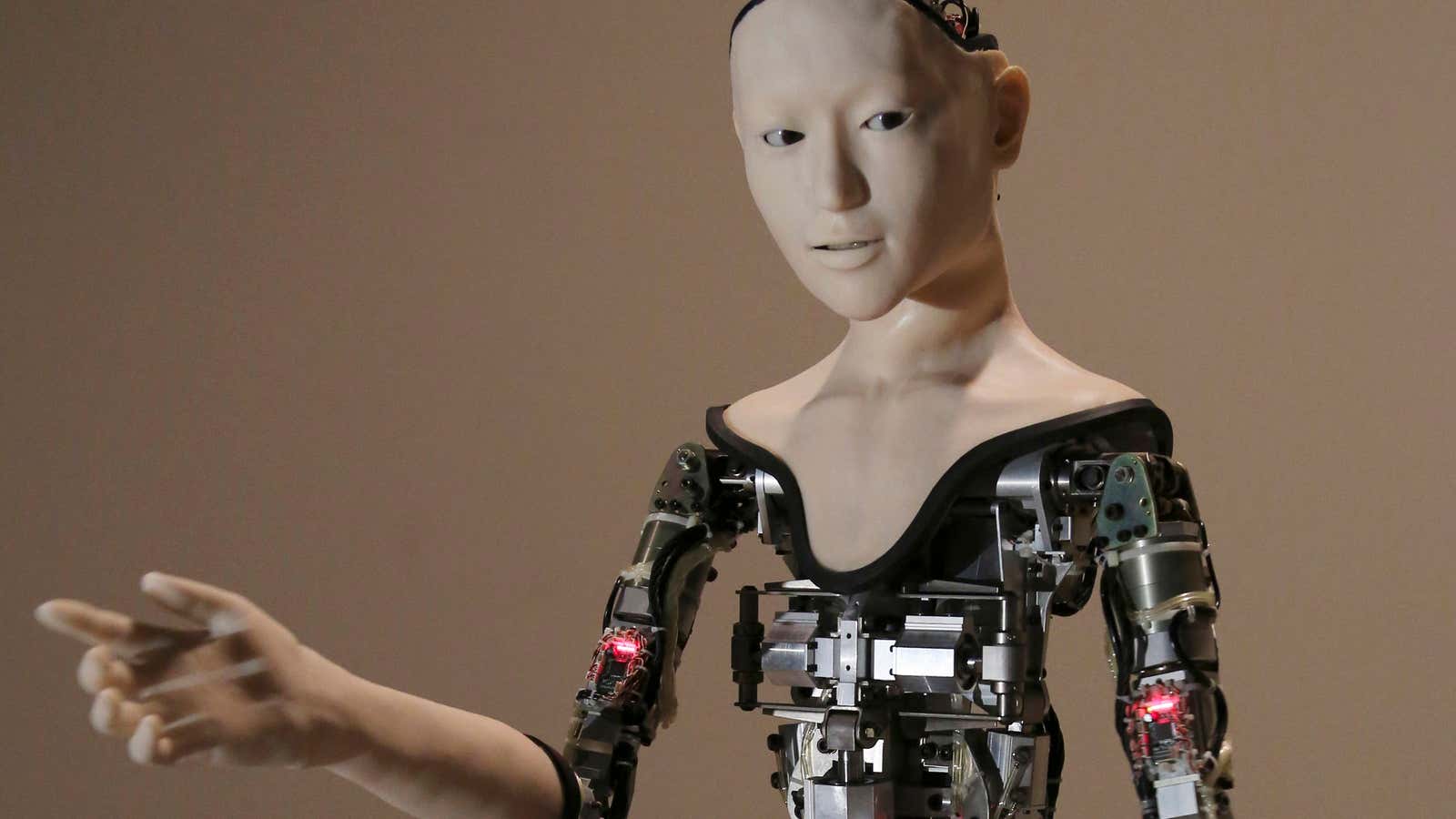

EA once concerned itself primarily with present-day problems of global poverty and its many effects. Now, he said, there was more of a focus on ‘long-termism’: the view that “the primary determinant of the value of our actions today is how those actions affect the very long run future.” EA supporters are increasingly drawn to concentrating their efforts on the problems they believe could end the human race once and for all. Two “existential risks” are a particular concern: hostile, apocalyptic artificial intelligence; and man-made pathogens that could hasten global collapse or even human extinction.

A focus on future lives isn’t so strange for EA. The movement suggests that all lives are equally valuable, wherever they might be. At least one natural extension of this principle means giving equal weighting, or something close to it, to lives that don’t presently exist—lives that are separated from the giver not by oceans or continents, but by decades or millennia. And because, as MacAskill says, “almost everyone who has a life is probably in the future,” it’s worthwhile focusing on saving potentially billions upon billions of hypothetical lives—especially if doing so is more cost-effective than saving the necessarily smaller number of present-day lives.

At the same time as some environmental campaigners or public health researchers applaud a falling birth-rate, many effective altruists suggest that a greater number of future, happy lives may also be the route to the best possible future civilization. (Population ethics, as it’s known in philosophy, is a thorny, relatively new area of study: Our moral duty to generations to come, as well as who they should consist of, is a contentious question.) But most people who studied the arguments, and who were generally sympathetic to the movement more generally, MacAskill said, took the view that “the loss of a future life, if that life would be good and happy and flourishing, is a bad thing.”

Still, if you’re trying to save the world, AI and manmade pathogens might not seem like the most obvious channels to take, especially as we stare down the barrel of climate crisis. Even within the movement, there are critics. Dylan Matthews, a Future Perfect senior writer and self-professed effective altruist who donated a kidney, has suggested that these focuses betray the biases of EA’s supporters. “At the moment, EA is very white, very male, and dominated by tech industry workers,” he writes. “It is increasingly obsessed with ideas and data that reflect the class position and interests of the movement’s members. … At the risk of overgeneralizing, the computer science majors have convinced each other that the best way to save the world is to do computer science research.”

MacAskill sees it differently. It wasn’t that global poverty isn’t still important, he said—rather that, “because the long, long future is so overwhelming, basically everything we do is, like, negligible compared to that. A lot of people take those arguments very seriously.” AI and man-made pathogens made fertile ground for research because, compared to climate change, they were “extremely neglected,” much like the humanitarian crises that the organization had always centered. At the same time, MacAskill added, continuing to fund anti-malaria bed nets might also have beneficial run-on effects that could help to secure a better future for mankind.

He was quick to clarify that even those who believed in this new course of action could see problems with it. “This is also, like, crazy for a large number of reasons. It means you have to believe we’re in an unusually influential period of history, which we should think a priori is fairly unlikely.”

Computer scientist and bitcoin billionaire Ben Delo is among the people swayed by these long-run future arguments. In his April 2019 Giving Pledge letter, Delo expressed an interest in “funding work to safeguard future generations and protect the long-term prospects of humanity. This includes mitigating risks that could spell the end of human endeavor or permanently curtail our potential.”

In a recent email to Quartz, he added: “My distinctive perspective might be that future generations matter morally. Or, maybe that’s a common view, and my distinctive perspective is just that we should take that idea seriously, and take action.” Practically speaking, this has involved making significant grants to the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, which tackles the questions of large-scale pandemics, and the UC Berkeley-based Center for Human-Compatible AI. He is also a seed funder of the Forethought Foundation for Global Priorities Research, which uses philosophical research to figure out “how best to positively influence the long-term future.”

But solving these problems requires more than just raising money, which EA had done “very well at,” MacAskill said. Instead, the movement’s key figures are encouraging very bright, EA-minded people “who really understand what’s going on” in these areas to pursue research careers to directly address the problems.

Telling altruistically-minded people to give their money away to help sick children in the developing world seems sensible enough. Suggesting that they do it to prevent what’s sometimes called the singularity—where AI becomes more powerful than all of human intelligence, and potentially hostile to its creators—may require more of a lift. But many EA researchers, who are experts in the field, think these risks are worth taking seriously. They’re interested, too, in questions of transhumanism: whether we’ll one day transition from biological to synthetic life, and what we should be doing now, if so. MacAskill talks about this almost as a certainty. “Whatever happens,” he said, “we want to be sure that we’re prepared.”

You can still be an effective altruist without supporting these more esoteric conclusions, of course. Instead of simply recommending effective charities, EA now runs four philanthropic funds of its own, which give out grants to deserving organizations. Donors can choose between traditional “Global Health and Development” or “Animal Welfare”, or help the movement continue its work with “EA Meta,” which writes grants to groups that do research related to the movement’s very principles. The fourth option, “Long-Term Future,” is the only one that explicitly focuses on these existential risks.

At the time of writing, the EA Meta and Long-Term Future funds were the ones with the least money in the bank. For now, EA supporters seem more comfortable donating to pressing, present-day suffering, instead of helping to solve problems that we may never actually encounter. But though MacAskill wants to give prospective donors the choice, he thinks finding the best solutions to these far-off issues requires sustained effort, right now. “We’re very strongly encouraging people to try to think this through for themselves, at least a little bit.”