The US House of Representatives voted decisively July 16 to condemn US president Donald Trump’s racist insults toward four freshman Congresswomen. But it almost didn’t happen at all.

Before the House passed a measure rebuking Trump for legitimizing “fear and hatred of new Americans and people of color,” chaos broke out on the floor over whether members of Congress could even use the word “racist” to refer to Trump’s tweets.

The debate broke down over familiar lines, with Republicans insisting that speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi was breaking rules by using the term, Democrats excoriating Trump, and everyone else wondering what exactly was going on in Washington, DC.

Turns out it was all a matter of decorum, House guidelines that aim to govern the behavior of House members on the floor. At the center of the confusion was the little-known “parliamentarian of the House,” a non-partisan civil servant who rules on Congressional conduct, and a manual written by US founding father Thomas Jefferson in 1801, which most Americans have also never heard of.

Here’s what happened.

Jefferson’s manual

The chaos began when Pelosi introduced the bill to condemn Trump, using the bill’s name, “Condemning President Trump’s Racist Comments Directed at Members of Congress,” and then called on Republicans to reject his “racist tweets.”

Republicans erupted. Doug Collins, the Georgia Republican and ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, called Pelosi’s remarks “un-parliamentary” and asked that they be “taken down,” or stricken from the record.

That’s because the House operates on the principle of stare decisis, a decision to stand by precedent that is also favored by US courts. And guiding this precedent in question is Jefferson’s Manual of Parliamentary Practice, a 1,500-page reference updated by the parliamentarian every Congressional session with new precedents.

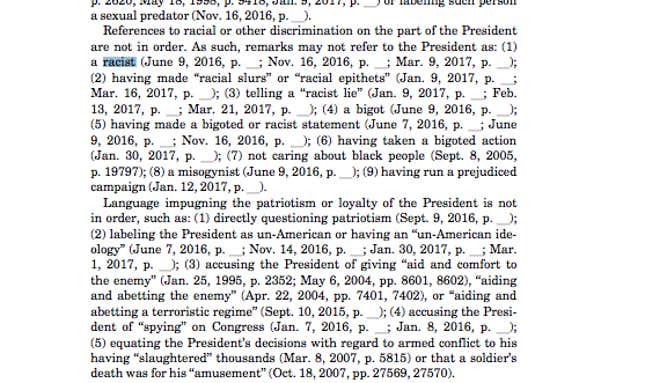

In the most recent edition, there are multiple new citations that calling the president a racist or a bigot, or even referring to bigoted statements by the president (page 203) had been determined in the past to be “out of order.”

Progress on the vote came to a total standstill as House members debated whether or not precedent forbid Pelosi from using the word “racist” to describe the president or his actions on the House floor. As the debate escalated, Emanuel Cleaver, the House chairman from Missouri who co-sponsored the bill, left the chair in apparent disgust:

Ultimately, it was left to Steny Hoyer, the Maryland Democrat, to deliver the verdict of Thomas J. Wickham Jr., the House parliamentarian since 2012. Pelosi’s remarks, he determined, were “not in order” and should not be used.

Precedent, not a rule

But that was just the beginning of the battle.

Jefferson’s manual deems that it is out of order “to speak irreverently or seditiously against the King,” Josh Chafetz, a Georgetown law professor, noted on Twitter as the fracas was happening. But that doesn’t mean there are actual “rules” against calling the president a racist.

“Should the Democrats believe that the precedents holding that calling the president a racist is out of order are themselves out of date and unwise, they can do away with them today,” Chafetz noted.

And that is essentially what happened. After Collins and other Republicans objected, the House voted to override the parliamentarian’s decision on Pelosi’s remarks, allowing them to finally move forward with a vote to rebuke the president.

The precedents preventing House members from calling the president “racist” cited in the latest version of Jefferson’s manual were nearly all added after Trump was elected. That’s because there have been so many more debates about racism since Trump came into office. These debates in turn led to objections by Republicans, and chair rulings that the word shouldn’t be used.

Pelosi isn’t alone. House members may have referred to the president as a “racist” multiple times on the floor, sometimes without objection. For example, minority members didn’t object when Jim McGovern, the Massachusetts Democrat, blasted Trump’s “racist rhetoric” hours before the July 16 vote.

Two versions of decency

Ahead of the final vote on rebuking Trump, Republicans expressed their concern about the deviation from established protocol. “I ask that all members take it upon themselves to uphold the decency of this organization,” House minority leader Kevin McCarthy, the Republican from Texas, said. “I hope we can rise to the occasion.”

Democrats, on the other hand, used the time to express their concern about the direction the United States is headed. “I know racism when I see it. I know racism when I feel it,” said John Lewis, the Georgia Civil Rights veteran. “The world is watching and its shocked and dismayed because we have lost our way as people.”

Hours later than expected, House member finally held a vote to condemn Trump’s racist remarks. It passed 240 to 187. Just four Republicans joined the Democrats.