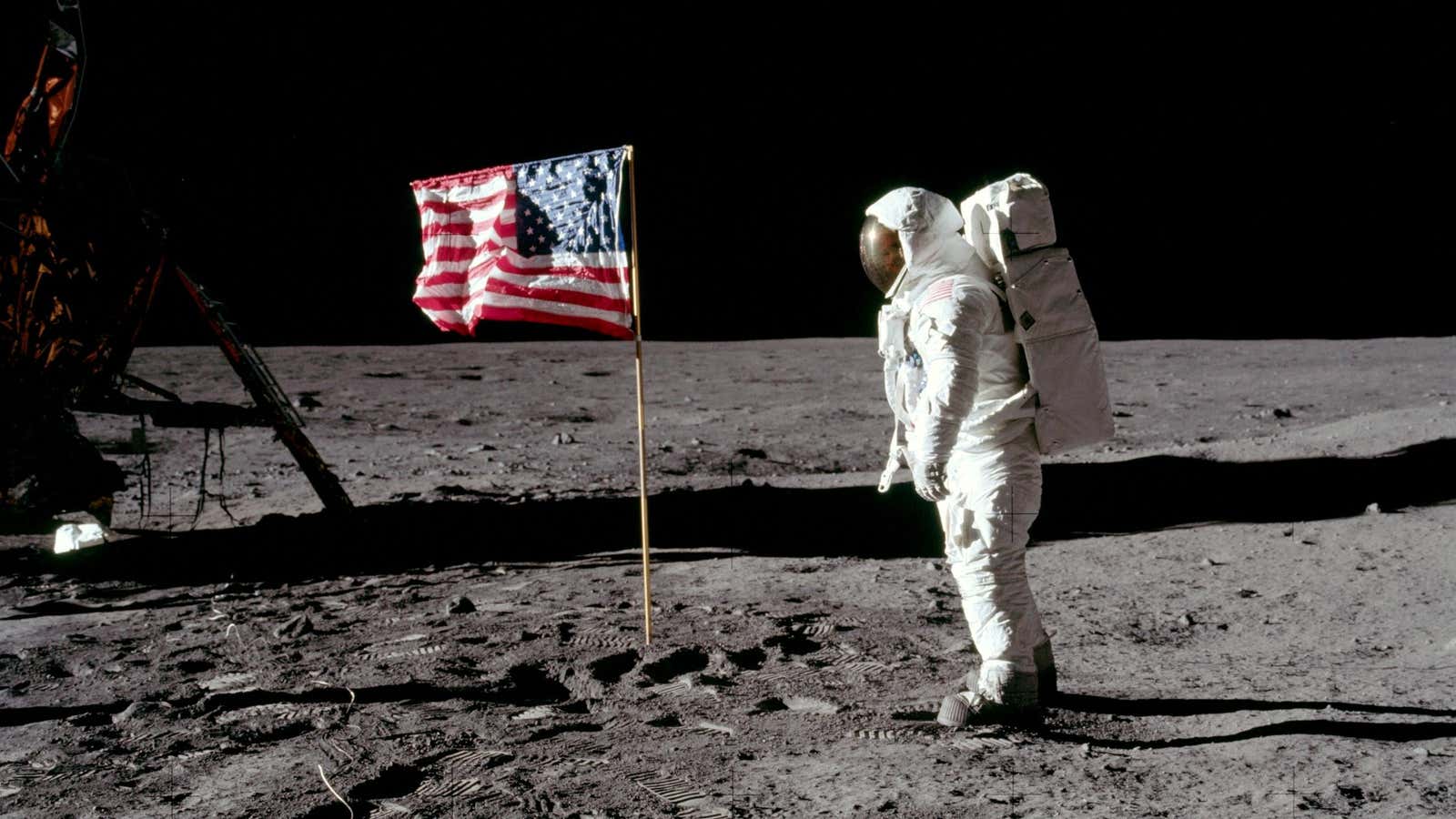

On July 20, 1969, an estimated 650 million people watched in suspense as Neil Armstrong descended a ladder towards the surface of the Moon.

As he took his first steps, he uttered words that would be written into history books for generations to come: “That’s one small step for man. One giant leap for mankind.”

Or at least that’s how the media reported his words.

But Armstrong insisted that he actually said, “That’s one small step for a man.” In fact, in the official transcript of the Moon landing mission, NASA transcribes the quote as “that’s one small step for (a) man.”

As a linguist, I’m fascinated by mistakes between what people say and what people hear.

In fact, I recently conducted a study on ambiguous speech, using Armstrong’s famous quote to try to figure out why and how we successfully understand speech most of the time, but also make the occasional mistake.

Our extraordinary speech-processing abilities

Despite confusion over Armstrong’s words, speakers and listeners have a remarkable ability to agree on what is said and what is heard.

When we talk, we formulate a thought, retrieve words from memory and move our mouths to produce sound. We do this quickly, producing, in English, around five syllables every second.

The process for listeners is equally complex and speedy. We hear sounds, which we separate into speech and non-speech information, combine the speech sounds into words, and determine the meanings of these words. Again, this happens nearly instantaneously, and errors rarely occur.

These processes are even more extraordinary when you think more closely about the properties of speech. Unlike writing, speech doesn’t have spaces between words. When people speak, there are typically very few pauses within a sentence.

Yet listeners have little trouble determining word boundaries in real time. This is because there are little cues—like pitch and rhythm—that indicate when one word stops and the next begins.

But problems in speech perception can arise when those kinds of cues are missing, especially when pitch and rhythm are used for non-linguistic purposes, like in music. This is one reason why misheard song lyrics—called “mondegreens”—are common. When singing or rapping, a lot of the speech cues we usually use are shifted to accommodate the song’s beat, which can end up jamming our default perception process.

But it’s not just lyrics that are misheard. This can happen in everyday speech, and some have wondered if this is what happened in the case of Neil Armstrong.

Studying Armstrong’s mixed signals

Over the years, researchers have tried to comb the audio files of Armstrong’s famous words, with mixed results. Some have suggested that Armstrong definitely produced the infamous “a,” while others maintain that it’s unlikely or too difficult to tell. But the original sound file was recorded 50 years ago, and the quality is pretty poor.

So can we ever really know whether Neil Armstrong uttered that little “a”?

Perhaps not. But in a recent study, my colleagues and I tried to get to the bottom of this.

First, we explored how similar the speech signals are when a speaker intends to say “for” or “for a.” That is, could a production of “for” be consistent with the sound waves, or acoustics, of “for a,” and vice-versa?

So we examined nearly 200 productions of “for” and 200 productions of “for a.” We found that the acoustics of the productions of each of these tokens were nearly identical. In other words, the sound waves produced by “He bought it for a school” and “He bought one for school” are strikingly similar.

But this doesn’t tell us what Armstrong actually said on that July day in 1969. So we wanted to see if listeners sometimes miss little words like “a” in contexts like Armstrong’s phrase.

We wondered whether “a” was always perceived by listeners, even when it was clearly produced. And we found that, in several studies, listeners often misheard short words, like “a.” This is especially true when the speaking rate was as slow as Armstrong’s.

In addition, we were able to manipulate whether or not people heard these short words just by altering the rate of speech. So perhaps this was a perfect storm of conditions for listeners to misperceive the intended meaning of this famous quote.

The case of the missing “a” is one example of the challenges in producing and understanding speech. Nonetheless, we typically perceive and produce speech quickly, easily, and without conscious effort.

A better understanding of this process can be especially useful when trying to help people with speech or hearing impairments. And it allows researchers to better understand how these skills are learned by adults trying to acquire a new language, which can, in turn, help language learners develop more efficient strategies.

Fifty years ago, humanity was changed when Neil Armstrong took those first steps on the Moon. But he probably didn’t realize that his famous first words could also help us better understand how humans communicate.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.