Ever since the world discovered that Finnish kids start school at seven, have very little homework, don’t take a lot of high-stakes tests, and yet still perform well on international assessments of reading, math, and science, the country has been a darling of the educational world.

Now the country’s early childhood care system is gaining attention, too.

Kids in Finland can start in early childhood education and care at age one, where they stay until they enter formal schooling at seven. It is not about toddlers sitting in desks and learning phonetics, but exploring the world, making friends, and figuring out how to be part of a community. From the time they enter the system, it is personalized for them: teachers design individualized learning plans with parents, and the toddlers themselves, based on values, likes, and dislikes (Johannes loves painting but hates the texture of paint, or Emilia loves to play with sand and can’t sleep without her blue teddy). Notably, these plans are not focused on developing academic skills or meeting developmental targets.

“Our kind of educational philosophy is also about wellbeing, about caring, about arts and aesthetics in life and in the beauty of life,” says Kristiina Kumpulainen, a professor of education at the University of Helsinki who just completed a chapter in a book about early childhood systems around the world. “When we look at early childhood education and the education plans, we remember and keep in mind this overall humanistic philosophy.”

If that philosophy sounds perfectly suited for the needs of young children—focused on play, tailored to their interests, and based on the world around them—the financing of it is equally appealing for parents. It’s free for those who can’t pay, and for those who can, the maximum fee is $300 a month for a full-time program (with meals). Indeed, one of the biggest challenges the system faces, explained Kumpulainen at a recent event in Washington, DC, was making sure that recent immigrants to Finland understand the massive array of services available, so that no child “is ever left behind.”

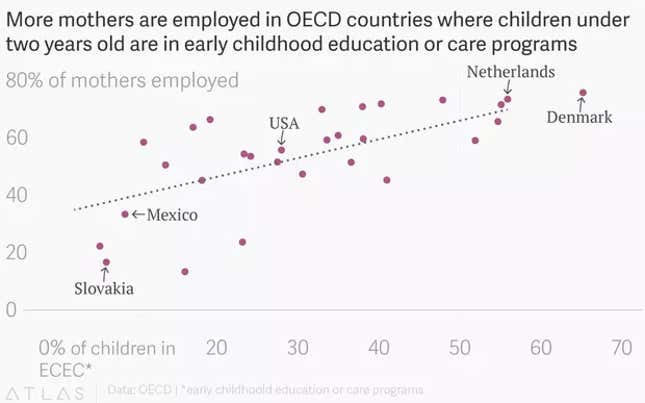

It’s a much different story in the US. According to one report, a third of American families spend 20% of their income or more on child care—7% is what the US government deems “affordable”. According to in a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, more than 60% of parents across all income brackets said it was difficult to find affordable, high-quality childcare in their community. Enrollment levels show the effect:

Finland is an exception: few countries have such comprehensive, well-funded, and child-centered systems. (When Kumpulainen finished describing Finland’s system at a recent event, the moderator, who works on early childhood policy in the US, said, “we’re are all so jealous.”) Most other advanced economies have far better offerings than the smattering of programs offered in the US, which are neither high-quality, comprehensive, affordable, nor built around the science that shows just how important that time is for infants and toddlers.

“At best I’d give us a ‘C,'” says Jessie Rasmussen, president of the Buffett Early Childhood Fund. “We’re inching along when we need bold steps forward.”

Head Start, the US government’s flagship early childhood program, provides education and health, nutrition, and family support services to 3- and 4-year-old children living in poverty. It costs about $10 billion a year to run, but it has limited availability: only 31% of kids who are eligible for Head Start are actually served and only 7% of those eligible for Early Head Start have access to a program in their neighborhood. A recent report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine said the US should aim to spend around $140 billion, or 0.75% of GDP, on early childhood education and care, close to the OECD average of 0.8% of GDP. (By comparison, the US government spends 2.4% of GDP on essential infrastructure—streets and highways, clean drinking water, and sanitation.)

It’s hardly as though there’s no demand for change. In 2015, First Five Years Fund, an advocacy group in the US focused on securing early learning opportunities for families, especially low-income ones, wrote in a a summary of polling that 91% of voters agree that a positive early childhood education experience “lays the foundation for all of the years of education that follow” (63% said they strongly agreed).

Six world leaders, and the US

Sharon Lynn Kagan, a professor of early childhood and family Policy at Columbia University’s Teachers College, has spent 40 years studying early education and care and more than three years studying six different early childhood education and care systems, all from countries with high-performing education systems (Hong Kong, Australia, Singapore, Korea, England, and Finland). She says the best systems in the world do two things: they have good “soil”, or infrastructure (such as consistent funding for services, effective monitoring of programs, good governance, family engagement, and continuous, thoughtful teacher development), which enables lots of good “flowers,” or programs, to bloom (like child care or pre-K education). The US, she says, focuses on the programs without really tending to the infrastructure. “We plant lots of flowers, but they are not doing their job because we pay no attention to the soil,” she says.

Other countries have invested energy and money in the soil. Hong Kong, for example, funds free, universal access to half-day early childhood education for all three- to six-year-olds (and is increasingly focusing on providing additional resources for children who may need more support, such as non-Chinese-speaking children). England has a national qualifications framework for teachers (and other occupations), which ensures a baseline of quality and makes training easier. Both Hong Kong and England have comprehensive inspection systems that collect and use data to monitor program quality (the infrastructure of data being used to support the education programs). Parents have access to the information to make informed choices about their child’s care.

Each system is born from its own history and values. England has a social welfare tradition that gives power to the government, and thus can trust it to set qualifications and monitor quality. Hong Kong combines high academic expectations of Chinese culture with a kindergarten curriculum that has British overtones, emphasizing free exploration and connecting themes to children’s everyday lives. Finland is a country with deep trust in government and institutions, so trusts it to design a child care system that is both holistic and grants educators huge autonomy.

“High quality is different in all of these countries, contoured to their context,” Kagan said at an event launching the second of two books that look at the six systems, called The Early Advantage: Building Systems that Work for Young Children. “We, as a nation, need to be very respectful of our uniquely American context.”

That context includes three powerful legacies: independence, localism, and entrepreneurialism, argues Kagan. The US was founded to escape the tyranny of government, so it does not look to government to solve problems like inequality—especially in the first three years of life. “We honor the privacy and the primacy of the family,” Kagan said in a webcast. Traditionally, when government gets involved with families it’s because they are deemed to have failed in some way. “This ethos says we want families to do it on their own,” she said. In the US, there is more trust of local over federal and strong faith in entrepreneurialism or private-sector solutions.

In other words, the US will never be Finland or England, but it can devise solutions that respect its own history. In Hong Kong, the private sector runs early childhood education and care centers, but the government monitors them and funds only those that meet their standards. Parents have access, and financial support, but the government doesn’t control the centers.

What’s the benefit?

High-quality early childhood education has been shown to have benefits that extend way beyond building babies’ brains (as if those aren’t important enough). An OECD analysis found that in most countries, even after accounting for socioeconomic background, students who attended early childhood education programs for two years or more scored higher on a standardized international science test for 15-year-olds than those who attended for less than two years.

What’s more, providing better and more affordable childcare options also allows more women to work, providing an impetus for economic growth and greater gender equality. For countries in the OECD, the data show that the more kids under two are enrolled in early childhood education or care programs, the more mothers work. In countries where at least 50% of kids are in programs, on average more than 70% of mothers work. In contrast, in countries where less than 20% of kids are in programs, on average only about 40% of mothers work.

Finland and beyond

It is a well-worn trope that the Nordics do all things better, and typical critiques argue that massive, diverse, decentralized systems like the US can’t learn much from a place with a population the size of Minnesota.

But other systems provide ideas and innovations, which can inform and influence public policy. Julius Richmond, the first director of Head Start, has argued that to change mindsets, you need strong knowledge base, public will, and a coherent strategy.

In Finland, the National Core Curriculum provides a framework for early education, but it is far from prescriptive (unlike in the UK, which has an early years curriculum with targets and goals). Municipalities can tailor the curriculum to meet the needs of local families, and the individualized plans give educators license to meet kids’ and parents’ needs.

Finland’s school-age curriculum has also undergone a radical transformation in recent years, from teaching traditional subjects to using a more interdisciplinary model. Teachers now use an inquiry and phenomenon-based approach, which favors experiential learning over books and lectures, and applies multiple disciplines to a single problem or subject area.

Since kids will eventually graduate from early childhood education into this curriculum, the early years mimic it. A lot of learning takes place outside, exploring forests and then reading about them in class, or talking about climate change and then watching movies that feature fairytales in the forest.

“We do not set developmental goals,” says Kumpulainen. “We describe activities we hope that teachers will cover during the year, but no child is expected to learn certain things at certain ages.”

No system is perfect. Some teachers in Finland think the new phenomenon-based model isn’t the best one for kids; in early childhood, many educators want more guidance on the individualized plans. And like every country in the world, pay for early childhood workers is a major issue. The government incentivizes parents—mostly mothers—to stay home until a child is three, a system which is being debated for its negative impact on women’s employment.

In Singapore, the government doubled its funding to early childhood education and care in 2012 and again in 2017; families can access these investments through subsidies, some of which are universally available and others that are targeted toward lower- and middle-income families. In South Korea, which is battling low birthrates, pregnant women get vouchers worth 500,000 won ($400) to cover pregnancy-related healthcare costs at designated medical centers; families can also get vouchers to cover the entire cost of full-day childcare for children up to two years old, and $200 per month for kids between three and five. As a result, 70% of kids younger than one and 86% of two-year-olds are enrolled in care.

Rasmussen from the Buffet Early Childhood Fund says Americans have to ask for a bold public investment in the first five years of life, especially in low-income areas. “We can’t keep walking away from generations of kids,” she said. “You can’t put that two-year-old on pause until we can figure out the answers.”