Southern Africa is not exactly big business for Esri, the world’s leading GIS mapping technology company.

In 2015, Esri earned $83 million in US government contracts alone. By contrast, according to the company’s financial statements, its Southern Africa outfit made just over $1 million in pre-tax profits that same year.

Yet the firm still opted to route those comparatively paltry earnings through Mauritius, a tiny island nation in the Indian Ocean whose controversial tax treaties and systems allowed Esri to legally avoid paying tax to some of the world’s poorest countries.

This is according to leaked documents that were among a trove of some 200,000 confidential records—collectively known as the Mauritius Leaks—belonging to the former Mauritius office of Bermuda-based offshore law firm Conyers Dill & Pearman, which were given to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and shared with dozens of journalists around the world, including reporters at Quartz. The resulting investigation provides a glimpse into how foreign companies and investors have been able to take advantage of the former French colony’s tax code to profit at the expense of poor nations.

The structure in Mauritius allows the company to pay an effective tax rate of just 3%, according to the leaked documents. That means that between 2013 and 2015, the company might have avoided paying about $550,000 in taxes when compared to the 2015 average African corporate tax rate of 28.14%. That’s a pittance for a company like Esri, but meaningful for nations it works in like Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Lesotho, which have among the lowest GDPs per capita in the world, and heavily rely on earnings from corporations doing business in their countries.

The Tax Justice Network, a research and advocacy group, estimates that governments around the world lose more than $500 billion per year to these kind of tax avoidance schemes, with poorer countries hit hardest.

“One little wad of cash can be the difference between a poor country building big infrastructure or not,” one Ugandan tax official told the ICIJ.

Esri’s public relations documents paint its work in Africa as a crucial component to tackling poverty and developing sustainable economies on the continent. In one of those documents, Esri describes how it “supports many sustainable development efforts on the continent of Africa.”

“People need to understand the underlying processes of disaster, hunger, disease, and poverty. GIS is an important tool for helping people map out plans for successfully achieving management strategies that are sustainable both at local and global levels.”

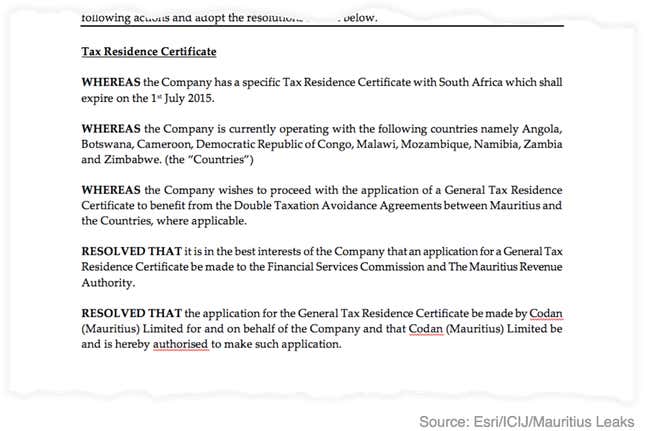

However, Esri Southern Africa’s business plan says it chose to base itself in the island tax haven because “Mauritius is an offshore jurisdiction with a wide network of double taxation treaties in interesting markets.”

In a statement to ICIJ, Esri chief operating officer Donald Berry sought to draw a distinction between Esri and Esri Southern Africa.

“This organization is one of our 87 international distributors. While these companies are largely independently owned and operated, they are closely associated with Esri and are the exclusive representatives for Esri in their territories,” Berry wrote, adding: “To our knowledge, nothing about our distributor’s operations in Mauritius, or in the other countries where they represent us, is inconsistent with the goals and values of Esri.”

It’s unclear what, if any, role Esri’s billionaire owner, Jack Dangermond, plays in running its Southern Africa distributor, but he does have a stake in its profits. Internal files show that Dangermond and his wife’s trust owns 20% of the company. Scans of their passports and latest gas and satellite bills are included alongside those of other shareholders in Esri Southern Africa’s 2015 application to open a Mauritian bank account.

Read more of Quartz’s reporting on how the Mauritius Leaks expose global tax avoidance.