If the art market were a country, it would be one of the world’s fastest growing: With 6% growth between 2017 and 2018, its expansion rate would be second only to China (which grew 6.6%).

But then, if the art market were a country, it would actually be three: Almost all of the $67.4 billion market is taken up by the US, UK, and China, which are home to 84% of all commercial art transactions, leaving crumbs to the rest of the world. France, the fourth-largest market, is far below the top three, at 6%.

Of these three countries, one stands out, not just because it’s the only non-Western country in the group, but because it came up from seemingly nowhere, essentially overnight: China.

In 2000, the Chinese art market counted for less than 1% of the global market; only about a decade later, in 2011, China was the single largest market for art in the whole world. Its relative size has shrunk since then, as the UK and US bounced back from the recession, but China has not just built an enormous domestic market for art: It has become a global art force, with its collectors and investors pumping money into prestigious auctions around the world. And, on the back of this astounding financial growth, Chinese art (particularly contemporary) has also become a global sensation, with some of its artists rising to international prominence, once again, in less than two decades.

A quick primer on how art is bought and sold around the world

There are an estimated 310,700 businesses in the art market—galleries, auction houses, and other institutions.

Sales nearly exclusively happen through dealers or auction houses. Dealers—that is, primarily gallerists who represent the artists—make up the majority of the market: In 2018, their sales accounted for $35.9 billion, while auction houses raised $29.1 billion

While most sales happen at the gallery or auction, art fairs and online sales are becoming important avenues to generate sales, with $16.5 billion worth of art bought in art fairs in 2018, and $6 billion bought online. Online sales have grown particularly quickly, doubling in the span of five years: They were $3.1 million in 2013, and has risen steadily since. Online and fair sales are important because they appeal to two growing groups of customers: millennials, and Asian collectors.

Although the vast majority of online sales are limited to lower segments of the market, where works are priced $5,000 or less, about 10% of online sales occur in the segment above $250,000, and this number may be destined to rise, considering that a whopping 93% of high-net-worth millennial collectors have acquired art online.

Chinese (and East Asian) collectors—who tend to be younger than western ones, making up about 40% of the customers, as opposed to older markets where they only make about 16%—are drawn to art fairs, too: 92% collectors from Hong Kong (and as many as 97% of those from Singapore) report having purchased from an art fair.

Painting by numbers

Whichever way one breaks it down—by country, by era of production, by author, by value—the art market is pretty concentrated.

The US, UK, and China make the most of the market in terms of geography. When it comes to art period, it’s modern art that takes the lion’s share of the market: Nearly 50% of the revenues from art sales come from art produced from the 1860s to World War II. Post-war art, the second-largest market, is less than half the size, making up 21% of the sales, followed by contemporary art, making up about 12% of the global market.

Things are similarly concentrated in terms of artwork value, resulting in polarization: high-end art is the best performing in terms of worth, with works priced upward of $10 million accounting for about a third of the market; on the other hand, affordable art is driving the volume of sales, with nearly 80% of works sold at auctions priced $5,000 or less.

Naturally, not every artist commands eye-popping prices: once again, it is a limited number of authors whose work has enormous value. With some important outliers (for instance Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvador Mundi, which sold for over $450 million in 2017), all these factors combine: high-value pieces by a limited number of western modern artists makes up the most valuable slice of the market. In 2018, of the nearly 39 million transactions in the art world, the 100 highest-paid works of art were altogether worth $3 billion, which means 0.00025% of the transactions are worth 0.5% of the whole market.

The global rise of Chinese art

Something else stands out when looking at the geographical concentration of art: It’s not just that three countries absorb nearly all of the market; it’s also that despite the expansion of global art, it is art coming from the west that commands the highest prices. According to Art Price, of the 100 works of art auctioned at the highest price tag (between $157 million and $14 million) in 2018, only 13 are by artists who aren’t from Europe, the US, or Russia—and all 13 of them are by Chinese artists.

The same is true looking at the top artists: With the exception of Yayoi Kusama, all the non-western artists who generated the top 100 returns in 2018 ($744 million to $48 million) are from China.

Chinese artists stand out both by overall turnover—six of them are in the top 20, bringing in between an aggregated $327 million (Zao Wou-Ki) and $107 million (Fu Baoshi)—and by record sales: Zao Wou-Ki, Su Shi, and Pan Tianshou all have single pieces of work sold for more than Jean-Michel Basquiat, Vincent Van Gogh, or Andy Warhol’s highest valued works. Furthermore, the work of 11th century calligrapher Su Shi had the highest average auction price, at over $59 million per piece sold.

The ultimate auction house wonder

While the most valuable western art gets sold in New York and London regardless of its origin, Chinese art is sold almost exclusively in China—both in Hong Kong, where the art market has been active even during the cultural revolution and following turmoil, and in mainland China, where the large auction houses established themselves in the early 2000s.

There are more than 6,400 auction houses in the mainland alone, of which at least 400 specialize in art, plus many in Hong Kong: this makes China the art-auction capital of the world in terms of volume of transactions (26% of all auctions are held in China), and the second largest market in terms of value (29% of the global revenue from auction, or $8.5 billion, comes from China).

Out of the top 10 auction houses in the world in 2018, six are Chinese: With the exception of Beijing’s Rong Bao Zhai, a state-owned enterprise opened in the 1950s on the legacy of a cultural institution funded in 1672 by the emperor, all of these art houses opened in the mid 1990s and 2000s.

This points to an important driver of the rise not just of China’s art market, but of the entire art scene: Newfound wealth.

With China’s exponential growth—the country’s GDP tripled between 1990 and 2000, then grew fivefold by 2010, and has doubled since—large amounts of capital became available to be invested in art, and the sector grew to accommodate such interest.

The rise of auction houses was also driven by the need for creative money laundering schemes, as well as avenues for bribery. The way auctions work, particularly when it comes to expensive works of art, makes them uniquely suited to questionable buyers and sellers: Identities are often concealed, sometimes even to the auction houses, and anonymity has been part of the charm of big art purchases for so long that it’s hardly questioned.

One scheme that became common in China is what is known as “elegant bribery”: An official would be gifted an artwork of low value, which is permitted by the party rules, then put it up for auction, which is also permitted. The same person who gave the gift, which was intended as bribery, would than buy it at an inflated price at the auction, effectively managing to indirectly bribe the official. This phenomenon became frequent enough not just to be one of the drivers of the expansion of auction houses all over the country, but to confirm the questionable reputation of Chinese auction houses, which have been found by several investigations—including a recent report by news agency Xinhua—to be tainted by fakes, collusion, and illegal practices.

This is not to say that the booming art market wasn’t also an expression of cultural appreciation: After the cultural revolution and China’s isolation, notes Tianyuan Deng, a PhD researcher in contemporary Chinese art at New York University, the Chinese audience had a hunger for the new and for culture that was near insatiable.

Still, the speed at which the art world developed couldn’t go hand in hand with an organic increase of production, which took a toll on the quality of new art being produced. After an initial phase when art was sold to western collectors and enthusiasts, several artists chose financial reward over artistic experimentation, often working on iterations of their own successful work—a mannerism of sorts—rather than exploring new avenues.

How to build an art scene

Because it had the resources to do so, China was able to build an art scene big enough to matter globally, even though it remains largely insular. According to Iain Robertson, an emerging-art researcher and author of New Art New Markets, an art market has to be able to sustain not just itself financially, but it must also foster a certain aesthetic.

Art requires recognition to gain value, and recognition needs institutions and centers of authority to grant it. Museums and galleries, curators, academies, collectors, researchers: The financial value of art depends on several factors that are, in theory, independent from the market.

Only two decades ago, China barely had any internationally accredited institutions able to put artists on a global map; rise in value of its art was driven by the rise of auction houses and the growing amounts of capital invested by collectors and speculators in Chinese artists. That has not changed too much to date: The Chinese classical works commanding the highest prices don’t find quite the same demand outside the mainland or Hong Kong, and they are the near-exclusive domain of Chinese art enthusiasts.

What is getting increasing attention, on the mainland and internationally, is contemporary art. While contemporary artists’ works don’t get the same auction results as classical paintings, and it’s taken time for them to obtain financial recognition, contemporary artists are growing in popularity and value, not just internationally, but within China. In 2018, the turnover from contemporary art and oil painting was $1.25 billion—a 34% increase year over year.

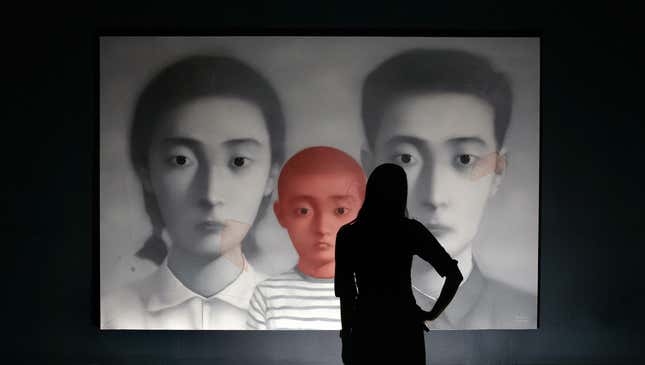

Artists like Ai Weiwei, Zhang Xiaogang, Fang Lijun, or Lin Tianmiao are acclaimed outside China, and their work is exhibited internationally in high-profile galleries, museums, and biennials. The same artists who, as China opened up its economy in the 1990s, struggled to get a few hundred dollars for their work, now sell for hundreds of thousands. They have become celebrities, having their work valued at the levels of the biggest contemporary art stars such as Jeff Koons or Yoko Ono. Interestingly, the movement of appreciation has often gone from the outside in, with foreign collectors and institutions championing contemporary Chinese art ahead of the Chinese ones.

There are many reasons for this. One is the government’s attitude toward contemporary art, which saw a remarkable change starting from the second half of the 2000s. While in 1999 the party was still issuing moratoria on performance art, from 2002 on, with Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, the state began supporting art, even promoting some artistic expression ahead of the Beijing Olympics.

It’s not that the party hadn’t been supportive of art at all: parallel to contemporary, experimental art and the artists critical of the regime and establishment, there has been a class of party-sanctioned artists whose worth has risen according to the party hierarchy and structure. In any case, these artists were never too far removed from the ones critical of the establishment, as there are a limited number of prestigious academies all artists attend. “People who are deep in the state system and people who are opposed to it are often in touch,” says Philip Tinari, the director of UCCA, China’s leading institution for contemporary art.

Institutions, too, have come up; hundreds of them: In the past few years, an impressive number of galleries and museums, many of which are private, have been opening not just in important hubs such as Shanghai’s Punan Canal or Beijing’s 798 Art Zone, but in more rural parts of the country. That is the case, for instance, of Yinchuan Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), a river-shaped construction in the capital of Ningxia autonomous region, a rather remote area in the north of the country. Opened in 2015, the museum has hosted several exhibitions and two biennials, and is often brought up as the quintessential example of both the mushrooming of cultural institutions in China and the risk of turning them into cultural cathedral in the deserts.

There are now several biennials in China, as well as publications and curators. While some warn the role of critics and experts is less independent than it is in other big art scenes—with galleries and official powers having large influence on reviews and coverage of art—there is a rudimentary foundation for an independent and thriving contemporary art scene.

Private museums, too—such as Shanghai’s Long Museum, Yuz Museum (housing Budi Tek’s collection), Tank Museum, Beijing’s Minsheng Contemporary Art Museum, or Nanjing’s Sifang Art Museum—have been booming, both because of a growing number of Chinese collectors with desire to display their acquisitions, and because of real estate incentives to build spaces to house cultural activities. In fact, the pace may have been too fast for art production, acquisition, and curation to keep up: All around China, hundreds of “ghost” museums and galleries sit empty.

How does contemporary art fit in all this?

It’s perhaps never possible to divorce art from its historical context, and in China, it’s particularly so. The development of contemporary art in the country goes hand in hand with one of the most peculiar post-war political environments. Unlike many other artistic scenes, China’s didn’t evolve organically from modern and postwar art; instead, it came up after a decades-long break in original artistic production during the cultural revolution, when the state essentially controlled all expressions.

In 1942, Mao Zedong spoke at the Yenan Forum on Art and Literature, stating the importance of a so-called “cultural army” tasked with bringing forward the revolution’s message. For decades after, China’s art growth was essentially stunted: people couldn’t attend art academies and educational institutions, and art itself was limited to propaganda, with very prescriptive subjects, media, and representation guidelines down to the choice of colors that was appropriate to represent a specific subject.

Artistic authorship ran counter to communist values, and artists were prohibited from pursuing their own research and creative interests. Masters like Wu Guanzhong, one of the founders of Chinese modern art, were forced to abandon production and art writing to focus instead on party-approved subjects and styles.

It wasn’t until after 1978, with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, that artistic education and pursuits were once again allowed in China. The 1980s were a time of great curiosity and experimentation in art and culture for a population that had been starved of intellectual stimulation.

With no market to speak of, the 1980s were a time of experimentation and research: artists often weren’t able to live off their art, and would combine their practice with other jobs, yet they had the urge to learn and explore. Academies became operational again, often attended by the same artists that had been tasked with propaganda art during the cultural revolution.

Hundreds of small groups of avant-garde artists emerged all over the country, essentially creating a whole artistic field anew. They didn’t continue the work of an existing generation of artists, but essentially filled the cultural revolution’s void of thought and creation.

In 1985, a landmark show by Robert Rauschemberg was held in Beijing; the same year gave rise to the ‘85 New Wave, a group of avant-garde artists who, between 1985 and 1989, produced provocative, controversial work that challenged social and party norms. The work of these artists culminated in an exhibition, titled China/Avant Garde, at the National Art Museum of China, in 1989. The show was closed after only two hours after its opening, following the performance of Xiao Lu, who fired shots at her own painting; only a few months after, the student movement exploded in the Tiananmen protests and following massacre.

The art community was stunned, and artistic production experienced another pause. Several artists left the country, while others took time off their practice as they coped with the political events.

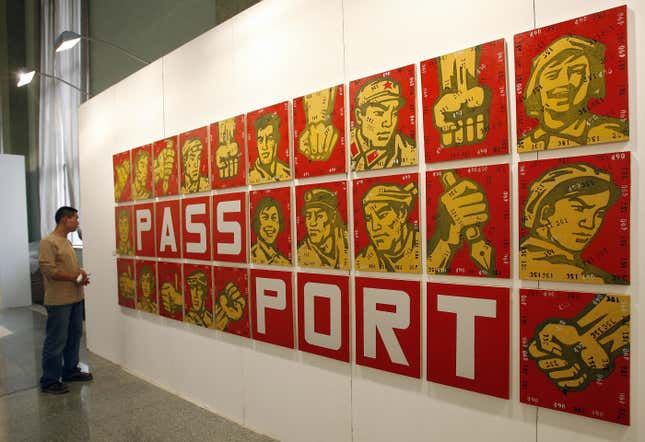

Then, in the early 1990s, Chinese art experienced a new start, with works of artists including Zhang Xiaogang, Fang Lijun, Yue Minjun. The works produced in this time were grouped under the label of “cynical realism,” and “political pop,” but these descriptions were applied after the fact, rather than being the result of a movement. While in the 1980s artists worked together, had manifestos, and consciously built certain artistic currents, production in the 1990s was far more individualistic.

At the time, Chinese art was heavily acquired by foreigners. The most extensive collection of contemporary Chinese art, for instance, now part of the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, comprises of over 1,500 artworks produced between 1974 and 2010, and collected at the time by Swiss businessman Uli Sigg (whose full collection counted 2,300 pieces before the museum donation). Posted to China as an ambassador, Sigg was, like other foreigners, able to acquire Chinese art in a moment when locals didn’t have the means, or interest, to do so.

A global art world

The link between Chinese contemporary art and the global (western) gaze runs deep, and isn’t limited to collectors. Beijing’s China/Avant Garde wasn’t the only 1989 show to have an impact on the history and success of contemporary Chinese art. In the same year, Paris hosted arguably the most consequential show for global art, and especially art from emerging countries. The show, hosted between the Center Pompidou and La Villette, was titled Les Magiciens de la Terre, and comprised works of 50 western artists and 50 artists from non-western countries.

The show was a starting point of sorts for the involvement of global artistic productions in the mainstream canon: events such as the Venice Biennale or Kassel’s documenta began including art from non-western parts of the world since.

About 30 countries were represented in the show, alongside western ones. From China, three artists had their work on display: Huang, Dexing Gu, Yang Jiecang. Still, China wasn’t given particular prominence—other countries, for instance Nigeria, India, Papua New Guinea, and Haiti—had more artists participate in the show.

Still, the exhibition expanded the horizon of contemporary art, starting (if slowly) a movement of acknowledgement and interest towards artistic movements outside the west, which continues to date.

This was especially important for the contemporary Chinese artists who weren’t entrenched in the party and found success abroad before China’s art scene was mature—and more importantly, encouraged by the political class. In the early 1990s, for instance, when he was curator of the Venice Biennale, Okwui Enwezor took several trips to China and selected some artworks that exposed their authors to international success.

“There are people in China, cultural conservatives, who write off contemporary Chinese art as too westernized,” Tinari says. But, he notes, the fact that Chinese artists might employ western techniques doesn’t necessarily mean they are derivative: He likens it to having an American operating system on a computer, which doesn’t make what is produced with it American.

“The concept of contemporary Chinese art is a western construct, it is a reflection of American categories,” says Xiaoyu Weng, a curator at the Guggenheim Museum. Weng believes the western fascination with Chinese art has translated into certain reductive reading of it, and using categorizations that, while helping Chinese art fit into a global discourse, failed to understand its complexity. “I think Chinese contemporary art is a made-up concept,” says Weng, who likes to highlight the different ways art is made in different parts of the country, and their uniqueness. This is not an easy predicament to get out of, she concedes: “The toolkit and framework we have to understand contemporary art is very Euro/American-centric,” she concedes, but she hopes that, with time, Chinese art is able to develop its own reading and understanding, away from the need to fit into some global trend. And this is already happening with a younger generation of practitioners.

What happens past the peak

One thing that might help Chinese art production (and its understanding) move away from western-centric practices is that, well, for all the hype and justified excitement, the Chinese art market—contemporary art aside—isn’t doing quite as well lately. For the past five years, the overall market has experienced serious decline, both in domestic and international sales.

Some of the very mechanisms that promoted the growth of the Chinese art market, and on its wings, the art world, are now starting to show their limitations. Auction houses, for instance, struggle as sold works go unpaid: In 2018, it happened to 41% of sold lots. This is happening for several reasons: Tighter cash regulations, the frequency of reproductions and fake works being sold by auctions, which leave collectors wondering if they have acquired fakes, and generally an inclination to bid without considering it a legal commitment to buy.

According to the most recent reports, it is unlikely that Chinese art will see the heights it reached in the late 2000s and early 2010s: The value of the art and volume of sales is likely to have peaked, and the future may also bring a shrinkage of institutions. Just this month, international art gallery Pace, which had been the first to enter mainland China in 2008, closed its doors, blaming the trade war, among other financial factors, for its business struggles.

It might not be terrible news, especially for the contemporary art production. High-end art, of the kind sold by Pace and galleries of similar prestige, is reserved to the very rich, but a shrinking of this market may allow artists to become more connected to the local community, producing work that can be bought by a larger number of people. As Weng puts it, there is a possibility (and the hope) that art will replace branded accessories in the Chinese upper middle class’s mind.

In a way, the same financial growth that allowed contemporary Chinese art to develop and thrive may now further help Chinese art by shrinking, allowing artists to pursue their research without the temptation, and obligation, of big commercial interest. It’s only recently, for instance, that art that isn’t a commentary on China’s political situation has been generating interest, which many observers consider a welcome change.

Regardless of what happens to the big foreign galleries in China and their mind-boggling financial growth, Tinari thinks the future is promising. “It finally feels like there is a public for what we are doing,” he says. Unprecedented numbers of people are willing to pay to attend shows and are looking to experience art.

If the interest in art continues to grow within China, even with a shrinking of the overall size of the artistic market and a return to a production that is more detached from the global world, an art scene could thrive. “And by the way, it doesn’t need to be big to be sustainable,” says Tinari.