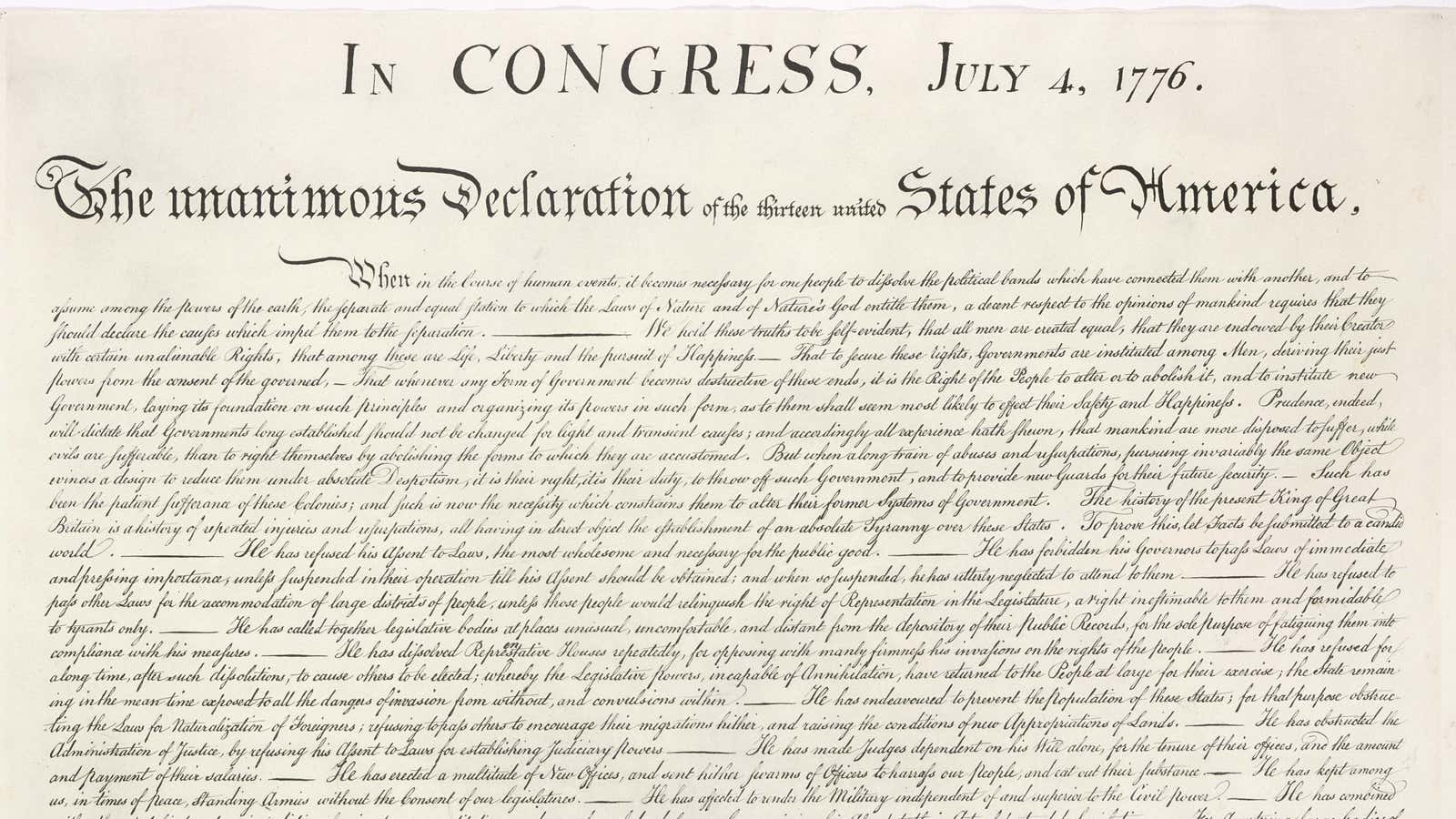

Earlier this month, when United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced a commission that would “review of the role of human rights in American foreign policy,” his declaration was met with fear. The “unalienable rights” laid out in the the US Declaration of Independence—“life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”—are inspiring, but highly unspecific. A refined definition could restrict rather than embrace human rights.

In Pompeo’s view, rights have proliferated over the past few decades; as he puts it, “rights claims are often aimed more at rewarding interest groups and dividing humanity into subgroups.” As his commission attempts to distinguish between “ad hoc rights granted by governments” and universal unalienable rights, several human rights groups warned that the commission could attempt to redefine human rights in the Trump administration’s image, particularly by limiting more recently embraced human rights, including women’s reproductive access and LGBTQ rights.

Their worries were reinforced by the makeup of the commission, which largely consists of legal scholars and political scientists who are religious, anti-abortion, and resistant to gay rights. One member among them sticks out: a philosopher.

Though philosophers are relatively unusual government advisors, they established the framing of human rights; the founding fathers of the US were inspired by English philosopher John Locke in their conception of unalienable rights. Pompeo’s modern-day selection: Christopher Tollefsen, a philosophy professor at the University of South Carolina with a focus on moral philosophy and practical ethics.

On the face of it, Tollefsen’s work presents many reasons to alarm human rights advocates. His work is grounded in Christian philosophers such as Aquinas, he’s opposed to abortion, and he believes that changing one’s gender is a sign of mental illness.

In other ways, though, Tollefsen doesn’t quite fit the administration’s mold. He is a philosopher that cannot be neatly placed in either a conservative or liberal camp; whereas political parties tend to have ideologies shaped by compromise and popular appeal, Tollefsen abides by strict principles.

For example, he’s absolutist in his belief that both torture and intentional killing is always wrong. Tollefsen argues that fetuses constitute human beings and, on this basis, abortion cannot be permitted. On the same strict basis, Tollefsen also argues against the death penalty and non-self-defense killing in war, and believes Americans should not be allowed to own assault rifles. “A law that makes weapons such as the AR-15 available seems to teach that private citizens are entitled to use the same kind and amount of force, and with the same intention, that police are,” he writes in an essay in the journal Public Discourse. “That, I think, is an error.” (Police could conceivably need an AR-15 in self defense as they protect not just themselves, but society at large, says Tollefsen. It’s unlikely an individual would need such a violent weapon for straightforward self-protection.)

Despite these absolutist moral perspectives, Tollefsen does not defend religious freedom in the same strict manner. Tollefsen believes in freedom of religion but advocates for the separation of church and state, and argues that the public good takes precedence over religious freedom. For example, Tollefsen says the state has a moral obligation to demand vaccinations that prevent disease outbreaks. Tollefsen cites the Vatican Council’s argument that all people have religious freedom “within due limits.” Failing to vaccinate children and so putting others at risk goes beyond those limits, in Tollefsen’s view.

None of these perspectives are likely to reassure human rights advocates. Deeply-held rights cannot be swapped around or traded, and for the many who believe access to reproduction and LGBTQ protections are fundamental rights, any attempt to restrict those will be an attack on human rights.

Judging by Tollefsen’s writing, he’s likely to be frank with the committee; the philosopher holds an absolutist view on the truth, believing it’s always immoral to lie. And so Pompeo will likely be presented with Tollefsen’s detailed arguments on gun rights, the death penalty, torture, and religious freedom. Of course, the commission on unalienable rights is hardly the only group weighing in on these issues, and even within the commission, Tollefsen is just one voice. But it’s a voice that now has the ear of the Secretary of State.