Not a week passes without an ethical misstep by Big Tech. From Facebook’s personal data overreaches to thousands of e-commerce sites that trick people into superfluous purchases to cities implementing facial-recognition systems without consent, the tech industry continues to stress-test trust.

In response, ethical guidelines have flourished. Whether a short checklist, visual principles, or lengthy treatise, most agree on core principles of privacy, safety and security, transparency, fairness, and autonomy. But despite the efforts of think tanks, tech companies, and government agencies, the principles haven’t been so easy to put into practice.

What if we took a different approach? Rather than focusing solely on generalizable standards or a prescriptive ethical code, we could instead emphasize an ethics of care. And what requires more care than our own romantic relationships?

Our love-hate relationship with technology

You may not want to admit it, but you’re already in a relationship with your devices. If you’re like most people, your smartphone is the first thing you look at in the morning and the last thing you look at before you fall asleep. It bears witness to your private moments. It circumscribes your friendships. It collects your secrets.

When those devices have a face or a voice, our impulse is to further anthropomorphize them like our human relationships. You’ve probably posed philosophical questions to Siri or asked Alexa for an opinion on something. Maybe you’ve even narrated the thoughts of your Roomba. As our internet-enabled things learn how to read facial expressions, tune in to vocal cues, and express themselves in a way that seems empathetic, we are likely to develop an even stronger bond with them.

The problem is that it’s a one-sided relationship—and we all know that never works out well. Like narcissistic manipulators, they often use their knowledge to bad ends. They take too much—time, attention, data—and give too little.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Relationships guide our moral compass every day. Many of us intuitively know a good relationship from a bad one. Honesty is fundamental. Consent is not just a one-time event. Boundaries are negotiated and revisited. And most of all, a good relationship is built on trust.

So what if we treated technology like a blossoming romance instead of unhealthy codependency?

Five steps to a better relationship with technology

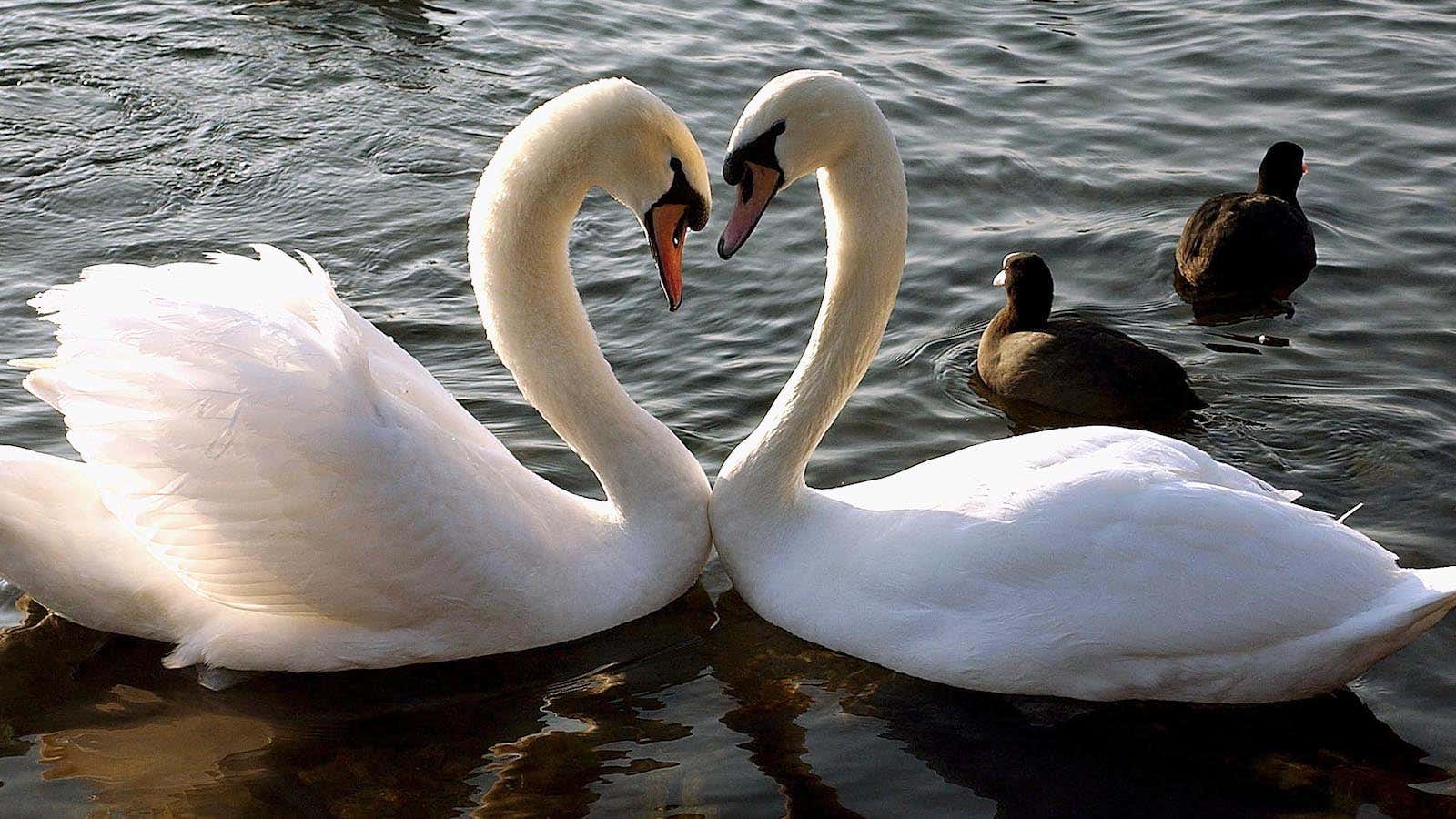

When it comes to technology, we go from meeting to marriage—and, all too often, betrayal—in mere minutes. The relationship arc is compressed to (1) “Hello!” (2) “Tell me everything about yourself” (3) commitment for life in the same amount of time it takes to drink your first daquiri. Similar to first dates, tech platforms woo us with vibrant design and privacy pop-ups that fan into a showy display, like a Mandarin drake looking for a mate, only to later neglect us.

What if a longer relationship trajectory became the norm instead? Anthropologist Helen Fisher says that there are three stages to falling in love: lust, attraction, and attachment. But as we have existing trust issues with tech, we should take it even slower. The phases below map to Mark Knapp’s relational development model. The University of Texas professor outlined 10 steps in relationships, from hello to goodbye.

Let’s focus on the steps for coming together, and how they might apply to our tech relationships.

Phase 1: Initiating

We often get to know other people before we even meet, whether by seeing them around the neighborhood or getting a glimpse on a dating app. Likewise, we might get to know a new app through word of mouth or reviews.

This is where most tech platforms have the upper hand on the first date, though: They already know a lot about us before we even click. In addition, they ask for unrestricted access before we’ve even been properly introduced.

Imagine if a new acquaintance asked to see the contents of your backpack or a week of your browser history before engaging in even the most banal small talk. Then imagine your new acquaintance sharing that information with hundreds of other people you didn’t know without telling you. Not cool, right? But what’s what many of our tech platforms do when they ask for a blanket agreement to terms and conditions just to initiate a relationship.

A more meaningful first date would start with transparency. Just as we might say to a new acquaintance, “I heard from my neighbor that we share an interest in birdwatching. What’s the most interesting bird you’ve spotted lately?” Imagine an AI chatbot—we’ll call it Robin—that’s just as transparent, “It looks like you came here after searching for hot duck in central park on Google. Do you want to read more about it?” Starting with a bit of background data is fine, so long as we are in the loop.

(And, as for terms and conditions, it’s not an all or nothing commitment now—or ever. After all, we’ve barely just met.)

Phase 2: Experimenting

If the first phase goes well enough, the next step is to get to know each other. In personal relationships, people look for common ground, shared interests, and mutual acquaintances. In human-machine relationships, we look for authenticity.

During this stage, tech platforms can slowly build trust by assisting us with small tasks as we learn where it fits into our lives. A nudge to upload a recent photo to your bird journal might be an acceptable interaction, while incentivizing long stretches staring a device when you’re supposed to be watching birds is not.

Because this point in the relationship involves more self-disclosure, consent becomes important. Robin the chatbot might ask for permission to collect and use specific data, “Is it okay to learn about your location? This information will help alert you to the next bird sighting.” But just because consent is offered this time around, doesn’t mean it should be an ongoing and irrevocable agreement, right? Robin should also therefore perhaps add, “Let me know how long you feel comfortable sharing this information. Is one week okay to start? You can change your mind later, too.”

Most tech (or human) relationships don’t get past phase two, due lack of interest, lack of trust, or both. As long as Robin doesn’t turn out to be a milkshake duck, let’s say we decide to take it to the next level.

Phase 3: Intensifying

If we have enough in common, we look for signals that the other person wants to go further. Intensifying in human relationships means giving gifts, assigning pet names, or even requesting some level of commitment.

In the tech sphere, that might translate into a thoughtful gesture, like a recommendation that shows revealing more personal data earlier in your relationship was worth the commitment. Robin might mention in passing, with your approval, “Hey, that duck you said you liked was spotted near your current location 2 days ago!”

Often the intensifying phase also involves tests like presenting a partner to family or a brief separation to see if the mutual affection will continue—or even “triangle tests,” where one partner sees if they can get a jealous reaction from the other.

In our tech relationships, tests might work, too. Imagine a third-wheel test, where we would ask to see whether there are other hangers-on—third parties—in this relationship that are accessing your data. Perhaps you could have a transparency check-in to consider what’s being collected, saved, or shared. Or even a fairness challenge to show how decisions are being informed by other people’s data, and whether that’s representative of a diverse population.

If you can survive those steps, maybe it’s time to take the plunge.

Phase 4: Integrating

After a few months of shared experience, we begin to get in sync. Integrating is the next step in human relationships, but it’s as much about setting healthy boundaries as it is about blending lives harmoniously.

Sometimes this translates to rules. Rules that fail tend to be too vague, too absolute, or simply never discussed. The worst are manipulative, like “If you don’t agree to these terms, you can no longer chat with Robin.” Setting healthy boundaries relies on open communication. You might tell Robin, “Please don’t import my sleep app data into the app. I feel this is unnecessary and disrespectful to my bird-watching desires.”

Integrating is a tricky balance of alignment and autonomy. If we can manage to get all our ducks in a row, the next phase is bonding.

Phase 5: Bonding

At this point, the relationship is official. After we bond, that’s not the end of things though. Relationships change in all kinds of ways over time, and we need to constantly check in with our partners to make sure everyone is still happy.

Coming together and coming apart is the ebb and flow of good relationships. There are frustrations and triumphs, challenges and reconciliations, small gestures for maintenance and grand efforts at revival. Good relationships are about mutual metamorphosis.

Successful long-term relationships therefore adapt to accommodate change. Machines aren’t yet nimble enough to adapt to us over time while helping us to grow. But perhaps we can become better together.

Imagine Robin, now using your pet name Holden, noting that the ducks in Central Park will be migrating soon. “Holden, some ducks are still here you know.” You reply, “Robin, maybe it’s time for us to try something new. What about an owl prowl?”

* * *

Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard believed people become their best selves through caring relationships. Following the trajectory of good relationships can provide meaningful guidelines for human-machine collaboration, too.

What humans don’t know about good relationships intuitively, they can learn. In a time when machines aren’t programmed but are taught, they can learn, too. By following these five relationship phases, the industry can begin to create a new kind of intuitive tech ethics that creates an empathetic relationship between people and technology, rather than ducking out.