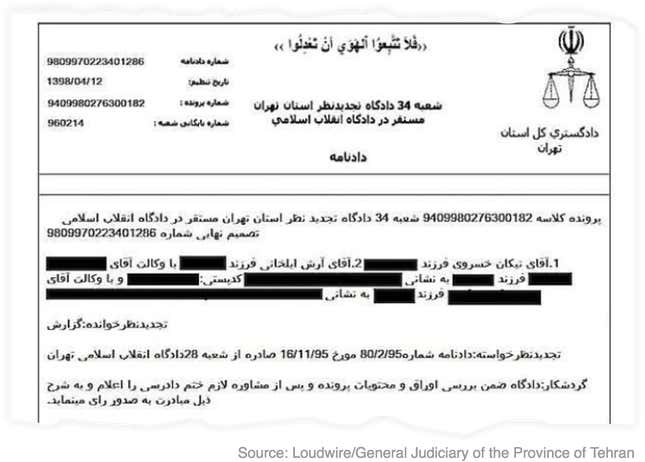

A judge in Tehran last month handed down harsh sentences to the two members of Confess, a well-regarded Iranian heavy metal duo prosecuted for making music the regime considers blasphemous. Singer and lead guitarist Nikan “Siyanor” Khosravi, 26, was given over 12 years in prison and 74 lashes for charges including “insulting the Supreme Leader and President,” “disturbing public opinion through the production of music containing anti-regime lyrics and insulting content,” and “participating in interviews with the opposition media.”

Bassist and DJ Arash “Chemical” Ilkhani, 24, received six years behind bars, with four years suspended, on charges of “insulting the sacred” and producing “propaganda against the state.”

But the men were already gone, and the sentencing symbolic. After their initial arrest and conviction in 2017, but before the appeals process began, Khosravi, who was under a state-imposed travel ban at the time, hired a smuggler to sneak him across the border into Turkey. Last December, Khosravi made his way to Harstad, a town of 25,000 in northern Norway.

Ilkhani, who had chosen to stay in Tehran for the appeals process, became extremely concerned after a contentious court hearing led him to believe he’d soon be jailed. In late February, he called Khosravi, who in turn contacted the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN), the Norway-based NGO that got him to Harstad, and asked for help.

Unlike Khosravi, the Iranian government hadn’t imposed a travel ban on Ilkhani. He too fled to Turkey. In early March, Ilkhani arrived in Harstad, which ICORN designated an “official city of refuge for musicians” in 2014.

Iran’s theocratic leadership does not tolerate dissent, and human rights groups have long decried its record on restricting freedom of expression. Women are regularly jailed for dancing or not covering their heads in public, and hundreds of journalists have been arrested, some even executed, for doing their jobs.

“Nikan and Arash are very good examples of how people who express themselves through the arts are soft targets for oppressive regimes,” ICORN program director Elisabeth Dyvik, who helped resettle the band, told Quartz. “The main source of their persecution are their words, their ideas, that in a country like yours or mine would seem mainstream.”

There are some 70 “cities of refuge” in the global ICORN network where artists and musicians at risk in their home countries can do two-year residencies. Applicants cannot choose their destinations, and are placed wherever there is room. Khosravi and Ilhkani ended up in Norway, where there is a thriving heavy metal scene, “by coincidence,” according to Dyvik, who said the band members were relieved to have ended up there.

“For us, of course [the metal scene] was a factor—our goal is to relocate people to places where they can continue their activities—but the first and foremost issue for us is their security,” Dyvik said. “But the city of Harstad specializes in receiving musicians and they have a very active music scene.”

Khosravi has so far had two solo performances in Sweden and the Netherlands, though he hasn’t yet played a show in Norway. Now that Ilkhani is there and Confess is back together, Khosravi would like to start gigging again as a band “in the near future,” he told Quartz. He hopes to play Norway’s Tons of Rock festival, which this year featured Kiss, Def Leppard, and Slayer, as well as the Inferno festival, a four-day black metal extravaganza that takes place in Oslo each April.

Khosravi and Ilkhani formed Confess in 2010, as teenagers. In Iran, all music must be approved and licensed by the government, and heavy metal is forbidden. The duo’s “illegal” repertoire includes songs such as “Encase Your Gun,” which takes aim at the Iranian regime’s extreme intolerance for dissent, and “Painter of Pain,” which makes liberal use of the word “fuck.” Their most recent track, “Evin,” describes the brutal conditions the two endured in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison.

In 2014, Khosravi started his own label, Opposite Records, which released the band’s second album, In Pursuit of Dreams, the following year.

A few days after the album came out, Khosravi and Ilkhani were arrested by agents with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The charges? “Blasphemy; advertising against the system; forming and running an illegal and underground label in the satanic metal and rock style; writing anti-religious, atheistic, political and anarchistic lyrics; and interviewing with forbidden radio stations.”

Khosravi and Ilkhani were remanded to Evin, where they spent 10 days in solitary confinement under the IRGC’s watch, before being transferred to a general population wing. Months later, Khosravi’s parents put their house up as collateral as bail for the two, which was set at the equivalent of $30,000.

A year later, Khosravi and Ilkhani stood trial. Although they were found guilty of blasphemy, the pair avoided death sentences thanks to a legal technicality.

“If you insult the Prophet you will get executed, because he’s dead and he can’t defend himself,” Khosravi told online metal magazine Loudwire last year. “But if you blaspheme God and question His existence, He can forgive you. That was why we didn’t get executed.”

It was during the subsequent appeals process that Khosravi snuck out of Iran to Turkey. He applied for an ICORN residency online, and eventually found his way to Harstad, where Ilkhani later joined him. They have reportedly been granted political asylum by the Norwegian government.

The Iranian authorities may still be keeping an eye on Khosravi and Ilkhani from afar, said Dyvik.

“I’m fairly sure they keep tabs on quite a lot of people,” she said, “but whether they will bother you or not also depends on how high-profile you are.”

As the duo’s case attracted attention from media outlets around the world, Dyvik believes they are somewhat insulated from retribution: “I don’t think there’s any risk [for them] in Norway.”

Khosravi said his family has been largely left alone by the regime since he left the country, but that he has received a handful of threatening messages online. Heads will continue to bang, regardless.

“This is not a thing that one can walk away from, and I’m saying proudly that I gave blood for my music,” Khosravi told Decibel magazine last year, “and I will keep this train going, even with no passengers.”

This article has been updated with comment from Nikan Khosravi.