I, like many American 16-year-olds in the year 2000, had a torrid affair with Napster. I wasn’t particularly tech-savvy, but I quickly figured out the basics. First, I had to download the software to my family’s desktop. Then, I could tell Napster that I wanted to make a digital copy of a certain song. The free service would find another person’s computer that had that song, and my computer would begin downloading a copy. After the file finished downloading, I could listen on Winamp—the music software I used at the time—and the quality was generally quite good. (Its simplicity was part of the sell; other, similar software existed but felt more complicated.)

My dad didn’t like my Napster habit. Understandably, he thought it was stealing. Most of those songs were not licensed for free distribution.

I knew it was wrong, too. I wasn’t some anarchist, “screw capitalism!” kid, but I knew it was hurting bands I liked, some of them not yet rich.

So my dad and I made a deal. If I downloaded three tracks off an album, I had to buy it. This way maybe Napster would actually make me spend more money on music. Napster gave me access to a larger number of albums I could sample, and if I really liked one, I would purchase the CD at the local Sam Goody music store, where I worked for a few months in high school.

I didn’t really follow the rules. I remember buying a few albums based on our agreement, but I also cheated a lot (sorry Dad). It was too hard to deny myself the free music then, and it would probably be too much for me today.

I was not alone in finding Napster’s music sharing irresistible. Starting around 2000, US music revenue fell off a cliff—from a peak of $21 billion in 1999 (in 2018 dollars) to about $7 billion in 2014, according to data from the Recording Industry Association of America. Few industries have ever experienced such disruption.

Thanks in large part to Napster and its ilk, music had become a public good, and there was no putting the cat back in the bag. Although Napster would get shut down, Spotify and Apple Music did eventually capitalize on how technology changed music from a scarce resource, to one that we all expected to have for free. The repercussions for who could succeed in the music industry would be massive.

Napster burned brightly and briefly. It was created in 1999 by the brothers Shawn and John Fanning, and founded as a business by Shawn and his friend Sean Parker, later the first president of Facebook. At the time, sharing MP3 files was challenging and the brothers thought they could make sharing a lot easier by giving people access to other users’ hard drives.

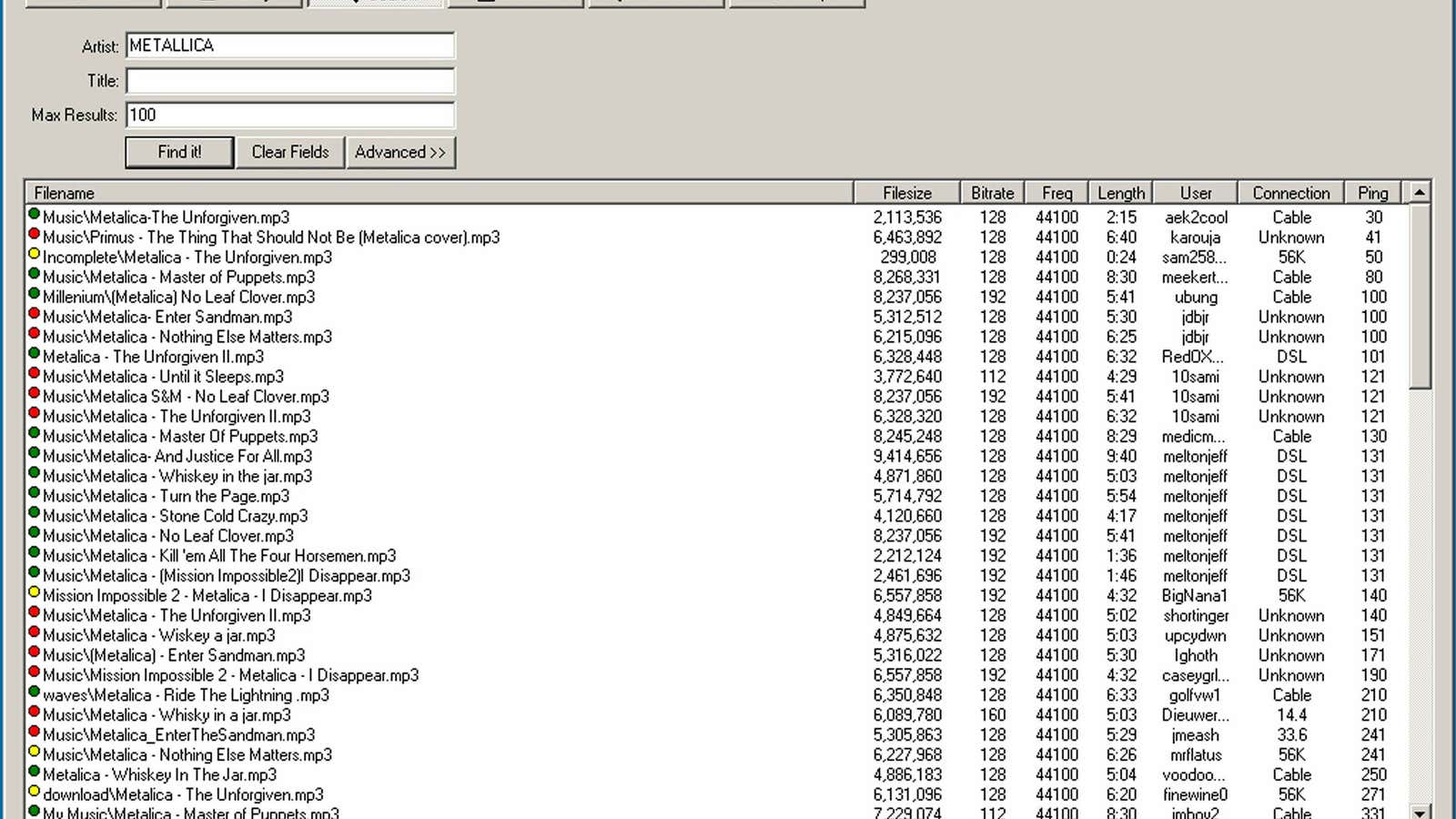

The service only existed as a peer-to-peer file sharing service from June 1999 to July 2001, but it caught on like wildfire. The internet was far less commonly used in 2000, but at its zenith, Napster still had about 70 million users globally (by comparison, Spotify has about 220 million today, after 13 years in operation). Napster gave users access to more than 4 million songs; at some universities, traffic from Napster accounted for about half the total bandwidth. Downloaded files from Napster sometimes brought computer viruses with them, but many, like myself, were willing to take on the risk.

Though a few artists, like Chuck D of the rap group Public Enemy, defended Napster for making music more accessible, most of the music industry hated it because its popularity meant they were losing money. The 20th century music industry was predicated on the idea of selling physical recordings of music—records, tapes, or CDs (live performances were a secondary source of income). At the time, CD album sales were at their absolute peak in the US, making up about $19 billion of the $21 billion in sales in 1999.

Napster was a company with a popular software in search of a revenue model, one it would never get the chance to find.

Napster was eventually shut down in 2001 due to lawsuit by the Recording Industry Association of America, the trade group for the US music industry. A US court found Napster was facilitating the illegal transfer of copyrighted music, and was told that unless it was able to stop that activity on its site, it would have to shutdown. Napster couldn’t comply. (After the shutdown, Napster’s brand and logo were acquired. They are now used by a small, but profitable, music streaming service owned by the media company RealNetworks, but the product is unrelated to the original Napster.)

But peer-to-peer music sharing did not just disappear. Sites like Lime Wire and Kazaa continued in Napster’s footsteps, and then also eventually were shut down. The global music industry would fight the softwares through the 2000s.

From the abyss, Spotify appeared. Daniel Ek, the co-founder and CEO of Spotify, has said that Spotify, launched in 2008, is a direct byproduct of his love for Napster, and his desire to create a similar experience for users.

“It came back to me constantly that Napster was such an amazing consumer experience, and I wanted to see if it could be a viable business,” Ek told the New Yorker in 2014. He says he thought he could create a “better product than piracy” by making streaming so fast that you wouldn’t even notice the loading time. He would avoid the trap that Napster fell into by getting music labels to agree to have their songs on his platform. To fund operations and licensing costs, he would sell advertising between songs (subscriptions were not originally part of the model), making music “free” like on Napster, but his program would be even easier to use and less likely to give you a computer virus. He thought his company would help save a declining music industry, and help people “discover better music.”

At least this is the story Ek tells. The authors of the 2019 book Spotify Teardown, an academic examination of rise of Spotify, say something very different happened. The book, written by a group of Swedish media studies professors, historians, and programmers, contends that Spotify was simply an opportunistic application of a technology that Ek developed, rather than effort to save the music industry.

Ek, who had been the CEO of the piracy platform uTorrent, founded Spotify with his friend, another entrepreneur named Martin Lorentzon. Both—Ek at 23 and Lorentzon 37—were already millionaires from the sales of previous businesses. The name Spotify had no particular meaning, and was not associated with music. According to Spotify Teardown, the company developed a software for improved peer-to-peer network sharing, and the founders spoke of it as a general “media distribution platform.” The initial choice to focus on music, the founders said at the time, was because audio files are smaller than video files, not because of a dream of saving music.

In 2007, when Spotify first publicly tested its software, it allowed users to stream songs downloaded from The Pirate Bay, a service for unlicensed downloads. By late 2008, Spotify would convince music labels in Sweden to license music to the site, and unlicensed music was removed. From there, Spotify would take off across Europe and then the world.

Today, Spotify, Apple Music, and Pandora dominate the music streaming economy. These companies‘ products are similar to Napster in that users can access nearly any song they wish. But unlike Napster, customers of these services pay for them—either directly, via a subscription (most are about $10 per month in the US), or indirectly, by listening to advertisements between songs. Users also don’t actually have physical or digital copies of the music, so they could lose access to it at any moment if streaming services were shut down or if they lost access to internet.

Though it may not have been Ek’s intention to “save” the music industry, his company might have done so by showing the viability of streaming. Because some of the revenue from streaming companies is sent on to labels, the music industry has finally started making money again. From a nadir of about $7 billion in revenue in 2014 (in 2018 dollars), US revenue rose to almost $10 billion in 2018. That is still less than half of the money the industry was making in 1999, but it’s progress nonetheless.

Not everyone has gained equally from streaming, though. The way streaming sites pay musicians tends to favor pop artists. Artists are paid by the stream; so a seven-minute jazz song earns an artist the same payout as a three-minute pop song (the money is funneled through record labels to the artist). Another factor that hurts less popular artists is that streaming services use “pro-rata” payment systems—all of the money generated from advertisements and subscriptions is put into a big pot and split up by the share of streams each artist gets in total. Studies suggest this model of payment hurts jazz and classical musicians compared to a “user-centric” system in which the revenue from each user is split up and given just to the artists they listen to. Spotify negotiates this payment arrangement with the large record studios, the details of which are not public.

Streaming seems like it is here to stay. Spotify and Apple Music are increasingly popular, and the music industry is not actively seeking a new method of selling music. Although the audio quality on Spotify isn’t as high as downloads or records, it is good enough to satisfy the average listener, and is likely to improve. Of course people also thought previous technologies, such as the CD, couldn’t be beat, and then something better came along. Perhaps advances in virtual and augmented reality, or 5G, will lead to ways of consuming music we can’t even imagine.

But for now, we have streaming, and it is almost certainly better for most artists than the wild world of Napster. Napster taught music listeners that they deserve all the world’s music at their fingertips. Creating rules for a music industry in which that is true but also serves artists well is a nearly impossible task.