WeWork’s co-founders must give $1 billion to charity over 10 years or lose some control of the company

WeWork wants you to know it loves the planet. The co-working company has banned meat and disposable cups from its US locations, pledged to donate $30 a month for each fruit water dispenser in its New York officers to charity, and committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2023.

WeWork wants you to know it loves the planet. The co-working company has banned meat and disposable cups from its US locations, pledged to donate $30 a month for each fruit water dispenser in its New York officers to charity, and committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2023.

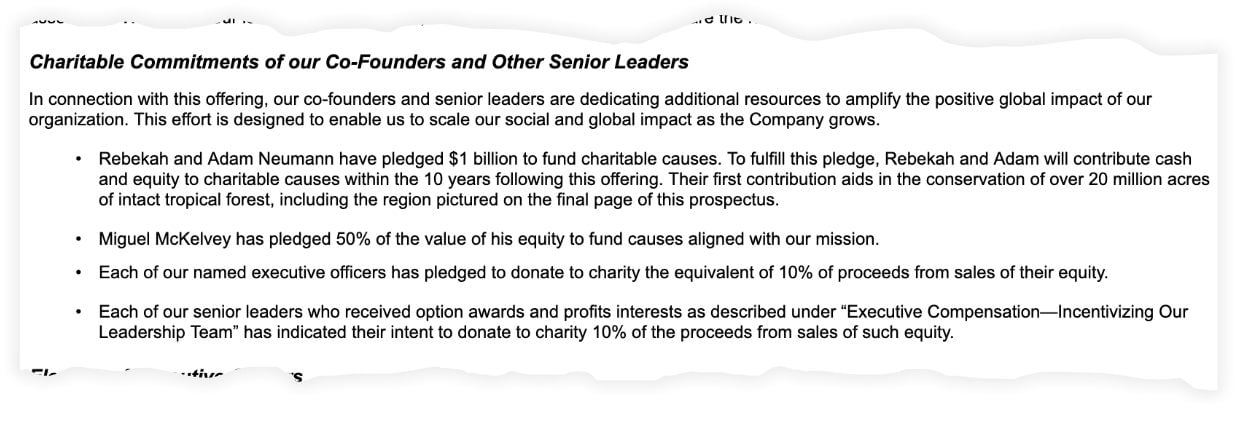

Now, according to the IPO filing WeWork unveiled yesterday, CEO and co-founder Adam Neumann and his wife Rebekah, also a co-founder, have pledged to give away $1 billion in cash and stock to “charitable causes” over the 10 years following the company’s IPO (which is expected next month). As part of this commitment, they’re starting with an initial contribution to support “over 20 million acres of intact tropical forest.”

Other high-ranking WeWork executives are also committing to charitable contributions. Miguel McKelvey, another co-founder, has pledged 50% of the value of his equity for unspecified causes “aligned with our mission,” the filing explains. It’s safe to say that “our mission” in this case probably means Adam Neumann’s mission, since he controls the company. Other named executive officers and certain senior leaders have promised or “indicated their intent” to donate 10% of the proceeds from their equity sales.

Such pledges in IPO filings are not uncommon, according to Melissa Berman, CEO of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors. “It’s a way for charitable organizations to benefit from the run-up that the IPO might create,” she says. According to SEC regulations, making these commitments ahead of the IPO may result in tax advantages for the donor and their causes alike.

“It used to be that when a company IPO-ed, they didn’t think about a corporate foundation for many, many years,” Berman says. But more and more, even companies still resolutely in “start-up mode” take their philanthropic responsibility seriously. “It is increasingly part of what the company wants to do from the minute it is a publicly traded company,” she says.

The catch is that if Adam and Rebekah Neumann don’t make good on that $1 billion contribution, they could lose some of their control of the company. WeWork, like many other tech companies, is going public with multiple share classes. (Uber’s decision to go public with a one-share-one-vote structure made it a noteworthy exception.) WeWork plans to offer Class A common stock that comes with one vote per share, alongside previously issued Class B and Class C shares with 20 votes each. These super-voting shares are almost exclusively held by Adam Neumann, who will control more than 50% of total voting power after the IPO.

If the WeWork CEO fails to contribute “an aggregate of at least $1 billion in cash or in kind, including securities and personal or real property” over the 10 years after the IPO, then the voting power conferred by his Class B and C shares gets cut in half, from 20 to 10 votes each, per terms outlined in the IPO filing.

Will this clause make any difference? Adam Neumann holds such disproportionate control of WeWork that it seems likely that even if the power of his super-voting shares were cut in half, he would still maintain control. Ownership stakes disclosed in WeWork’s IPO filing show that Neumann holds 2.4 million Class A shares, 113 million Class B shares, and 1.1 million Class C shares. The company’s next-biggest shareholder is investor Softbank, which holds 114 million Class A shares and no Class B or C stock. Only a handful of other people listed in the filing have any Class B shares, each amounting to less than 1%, and nobody aside from Adam Neumann has any Class C shares.

In other words, Neumann and Softbank hold roughly the same number of shares, but Neumann’s come with 20 times the voting power. Even if that got cut in half, he would still have 10 times the voting power of the company’s next biggest shareholder.

Alejandro Ortiz, an analyst at private securities marketplace SharesPost, notes that the language tying voting rights to charitable commitments is unusual, but that corporate social responsibility is “a huge thing right now,” he says. “Every company is trying to show in one way or another to investors and the public that beyond trying to make money we care about the world we live in.”