A day doesn’t go by when the “Productivity” folder in my RSS feed doesn’t recommend some shiny new task manager/to-do-list-app/project management tool.

I confess I often download them with high hopes….

…only to delete the app a few hours later and revert back to the way I’ve always gotten things done.

My task management system is rooted in the way my father helped me plan my school work. I was born in India but mostly raised in Abu Dhabi by parents, who set an excruciatingly high bar for academic achievement. My particular problem with studying was focus. I was good at my work, but I seldom got around to doing it. I had a tendency to drift off, let assignments pile-up, and then work myself into a funk as deadlines began to explode around me.

Realizing these shortcomings in my character, my father created a system of small rewards to help me get through schoolwork. The fundamental basis of the system is counter-intuitive: If you want to get five tasks done, my father always said, first find five additional but enjoyable tasks to do.

Let me explain.

There are three hurdles to getting things done well, none of which have to do with a paucity of smartphone apps. First of all, just waking up in the morning and looking at a to-do list is off-putting. I am not one of those people who explode out of the bed each morning, eager for achievement.

Second, busy people tend to focus on the easier tasks, leaving the hard or boring for later. But those pending jobs pile up and become a productivity nightmare.

Third, what is the point of it all? How do you keep yourself motivated to trudge through these to-do’s one after the other?

When I was a teenager, my father’s trick was to arrange my schedule in such a way that after each task I was rewarded with something. Thus arduous geometry homework was followed by the highlights of a cricket match on TV. That would be followed by a geography map-drawing assignment (puke) and then a brief break with my Gameboy, and so on.

I was allowed, even encouraged, to plan my tasks around the rewards. The only stipulation was that everything—task and reward—had fixed time spans, so that I didn’t linger too long on any one thing. If something took longer than I planned, I either forfeited my reward time, or re-planned my day. Algebra taking twice as long as planned? No problem. I’ll just carry on and skip the cricket highlights at 2 pm for Small Wonder at 4:30 pm.

The most satisfying thing about this system was often not the rewards, but the crossing out of assignments on my task list.

Being able to tell everybody, especially myself, that I’d completed math, English, Hindi, and social science homework exactly according to plan … was actually fulfilling.

Today I still use the same micro-rewards system. But in a modified way.

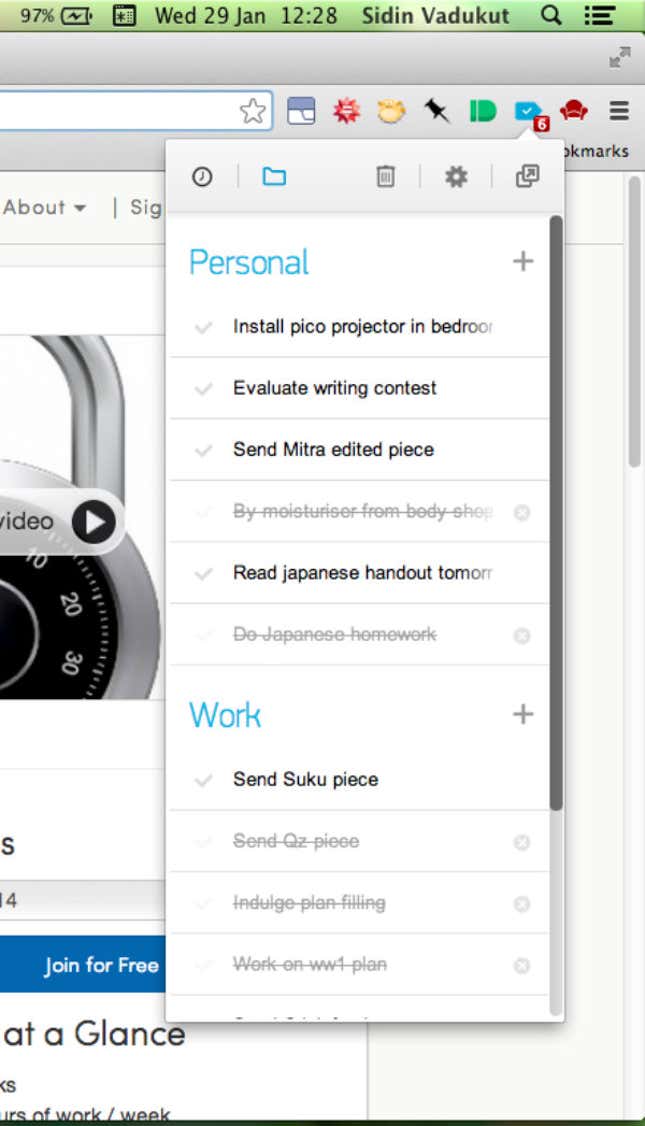

First, I write down everything I need to get done that day. A piece of paper will do well enough. Recently, I tend to use the Any.do app. (It works on both iOS and Android and has a useful Chrome extension.) My current Any.do list with some completed tasks looks something like this:

Next, I populate the list with a whole bunch of rewards. This could be anything from “sushi lunch” to “research Bluetooth speakers.”

Besides these leisurely activities, there is one more type of reward I use—a reward task. A type of task that is rewarding, but also adds to my productivity.

You can probably relate to these tasks if you think of them as co-curricular activities for grown-ups. These are less serious, somewhat informal tasks—some that might even bring us joy. In my case, one of my editors may have asked me to review a certain book when time permits. Or I may have a long overdue telephone call with a policeman in Nagpur as part of the research of my next novel: a murder mystery. Or maybe some homework from one of my MOOC courses I’ve been taking recently. (Currently I working on this one on Cryptography and, as you can see in the screenshot, taking real world Japanese lessons.)

I call these “reward tasks” because even though these tasks are important commitments, they are fun and I look forward to them with great enthusiasm. A little ingenuity while designing reward tasks helps. So instead of just “buy beer,” I split the task into two rewards: “read beer reviews online” and “go buy great beer.”

Next, I plan my day in such a way that each serious task is alternated with a reward or a reward task. The tougher the task, the more enjoyable should be the reward that follows. Once you’re done with all your serious tasks (like exercising), end the day with a couple of reward tasks to cool down.

This system works for me for a few reasons. It nudges me to take on the tougher tasks first, so I can enjoy the bigger reward tasks faster. This way the key jobs get completed. Second, the thought of the sushi lunch helps me stay focused on the task at hand. Third, I enjoy being able to sit back at the end of the day and see an entire list of tasks crossed out, even if half of them were things I loved doing anyway.

Finally, I tend to enjoy my leisure time more, if I have had a packed day leading up to it. Even if there are issues from work bothering me, I tell myself that I have accomplished so much today, I should just let go and have fun.

This is a simple system that admittedly involves a certain element of self-delusion and self-manipulation. But it gets work done. And, now that I have finished delivering this column to my editor, I can go have a beer. Win.